Palestine was the name applied by Herodotus and other Greek and Latin writers to the Philistine coastland, and sometimes also to the territory between it and the Jordan Valley. Early in the Roman Empire the name Palestina was given to the region around Jerusalem. The Byzantines in turn named the province west of the Jordan River, stretching from Mount Carmel in the north to Gaza in the south, Palestina Prima.

ROME AND BYZANTIUM

In 70 AD, Roman Emperor Titus quashed a Jewish revolt in Palestine, leveling Jerusalem and its Temple. Following a second revolt (132-135), Emperor Hadrian erected a new, pagan city, Colonia Aelia Capitolina, on Jerusalem's ruins, barring Jewish entry. Post-Hadrian, the Christian population in Jerusalem swelled, especially after Emperor Constantine I (d. 337) converted to Christianity. Constantine built the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and his successors, notably Justinian (d. 565), enriched the land with numerous churches and religious monuments. The Byzantines restricted Jewish access to Jerusalem to once a year to mourn at the Temple site, maintaining its desolation in accordance with Jesus’ prophecy in Matthew 24:2.

ISLAM AND THE UMAYYADS

Before Islam's rise in the seventh century, the Christians of Palestine and its Arab inhabitants, some of whom were also Christians, continuously intermingled. Initially, Prophet Muhammad and his followers prayed towards Jerusalem, not Mecca.

In 637 AD, the Arabs, led by Caliph Omar, captured Jerusalem from the Byzantines, treating its inhabitants with unprecedented clemency. In the words of Sir William Fitzgerald: "Never in the sorry story of conquest up to that day, and rarely since, were such noble and generous sentiments displayed by a conqueror as those extended to Jerusalem by Omar." Omar's efforts to identify and honor the sites of Muhammad's ascension emphasized the spiritual significance of Jerusalem.

The Umayyad dynasty (661-750), with Damascus as its capital, further honored Palestine. Abd al-Malik, the fifth Umayyad caliph, and his son Walid constructed the Dome of the Rock and the adjacent al-Aqsa Mosque.

THE ABBASIDS

The Abbasid dynasty (750-1225), based in Baghdad, succeeded the Umayyads, reaching its peak quickly but later seeing many regions fall under semi-autonomous rule. Despite initial restrictions, the Abbasids gradually allowed Jews to reside in Jerusalem, responding to Christian interests by facilitating pilgrim accommodations. This era, marked by religious coexistence and cultural exchanges, set the stage for the evolving dynamic of Jerusalem and Palestine.

THE CRUSADES AND COUNTER-CRUSADES

Arab and Muslim dominion over Palestine was disrupted by the Crusader invasion, leading to the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1187). The Counter-Crusades, spearheaded by Saladin (d. 1193) and his successors, continued until 1291, culminating in the recapture of the last Frankish strongholds, Caesarea and Acre. The Crusaders' entry into Jerusalem was marked by the torture, burning, and massacre of countless defenseless Muslims and a small number of Jews seeking refuge in their synagogue. In stark contrast, Saladin's conquest of Jerusalem in 1187 mirrored the reverence and compassion for the city shown by Caliph Omar centuries before. Saladin's initial act was to purify the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque. He restored properties to Muslim families displaced by the Crusades, reintroduced the madrasah system, and established a hospital and hostels for scholars.

Under Saladin and the Ayyubids, Christians were allowed to live and worship freely in Jerusalem, which remained accessible to European pilgrims despite fears of another Frankish conquest.

THE MAMLUKES

In 1260, the Mamlukes of Egypt succeeded Saladin's Ayyubid descendants, ruling Palestine until the Ottoman conquest in 1517. They expelled the last Crusaders and defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Ayn Jalut, preserving the country. The Mamlukes preserved the administrative division of Falastin, established by Caliph Omar, and reorganized the region into six districts: Gaza, Lydda, Kakun, Jerusalem, Hebron, and Nablus, making it a vital link between Cairo, Damascus, and Aleppo.

Jerusalem received special attention from the Mamlukes, who reduced taxes, improved religious sites, and built facilities for the poor. Muslim geographers and historians, including Yakut, Abu'l-Fida, and ibn Battuta, extensively documented Palestine's rich religious and cultural landscape during this period.

THE OTTOMANS

In 1516, the Ottoman Empire—founded by Turkic tribesmen in Anatolia, who then established their capital on the ruins of the Byzantine Empire in Constantinople—moved against the Mamluk rule in the Levant. The Ottoman forces defeated the Mamluk armies and conquered Bilad al-Sham, including Palestine. This marked the beginning of four centuries of nearly uninterrupted Ottoman rule over Palestine.

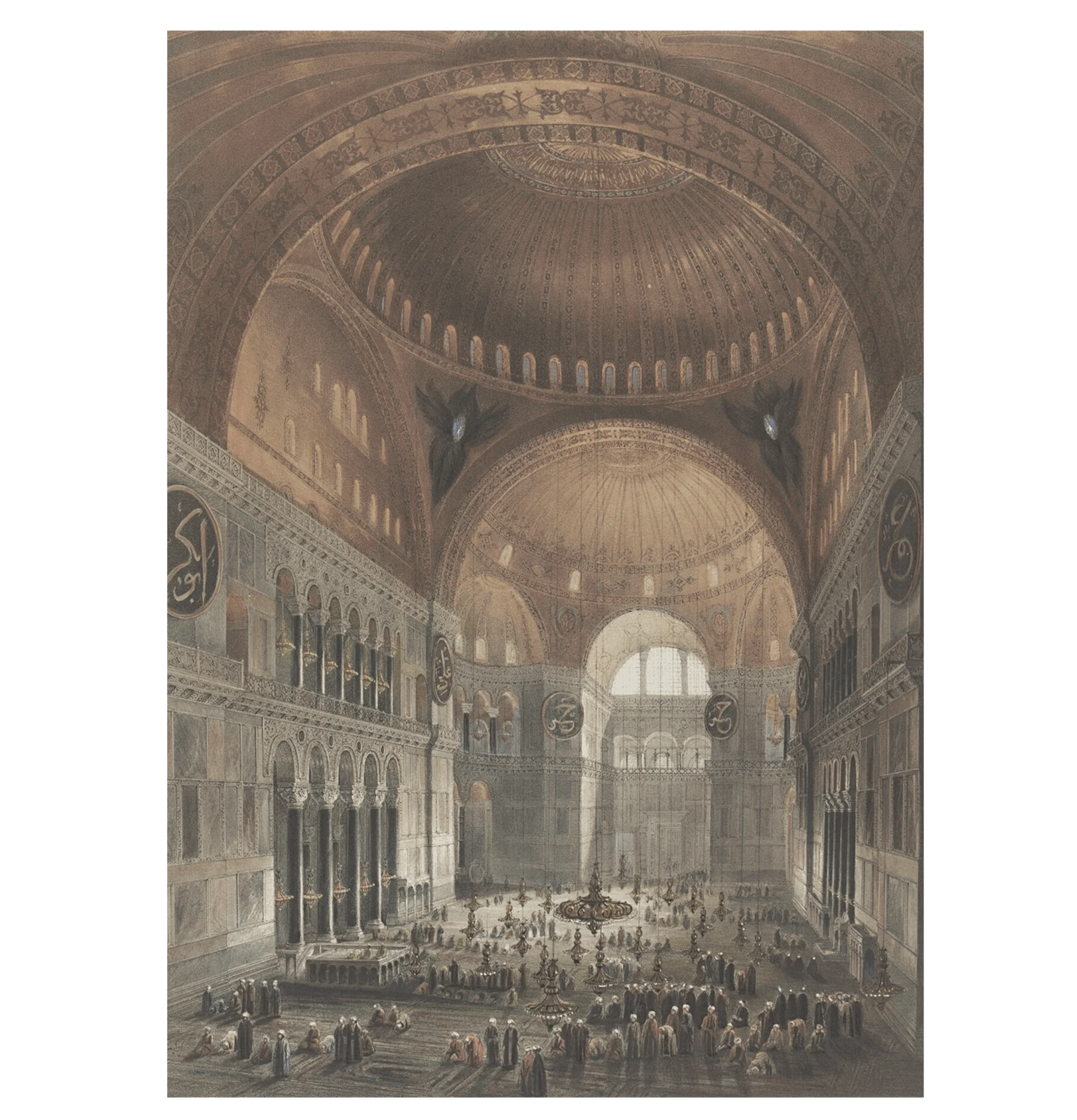

Sovereignty over Jerusalem held special significance for the Ottomans who, early on, embarked on projects to rebuild the city's walls and renovate the Dome of the Rock (1537-1540). The majestic walls encircling the Old City of Jerusalem, built by Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-66), demonstrate Jerusalem's significance within the Ottoman realm. Equally significant is the endowment made in 1552 by Hürrem Haseki Sultan (known in Europe as Roxelana), the favored queen of Suleiman. She constructed a complex in Jerusalem for the poor and the needy, which included a monastery.

The Ottomans meticulously upheld the Muslim tradition of tolerance towards Christian religious interests in Palestine, acknowledged the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, and safeguarded Latin clergy through French guardianship. They also acknowledged Christian and Jewish rights to sites of religious significance, managing a complex arrangement of privileges and access rights to these sites through a system known as the status quo.

The Ottoman Empire welcomed hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing persecution from Spain and other parts of Christendom. However, the majority, similar to earlier centuries after the Crusades, opted not to settle in Palestine. Consequently, the number of Jews in Jerusalem in the first century following the Ottoman conquest decreased from 1,330 in 1525 to 980 in 1587.

Yet despite relative calm in religious matters, Palestine was also periodically the site of local, regional, and global political struggles.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, a number of processes unfolding both regionally and globally shaped the development of events in Palestine.

Foreign powers began to exploit the Ottoman Empire's relative weakness to impose economic and political concessions upon it under the framework of capitulations, which gave foreign subjects in Ottoman lands privileged status—exempting them, for example, from taxation or local prosecution. Although capitulations had been in place since the Ottoman conquest of the Levant, European powers expanded their privileges as the empire faltered and extended them to local clients. The Zionist Movement and its European supporters were no exception, exploiting this system to foster Jewish immigration to Palestine despite local opposition.

Before Zionism's rise, Palestinians and Jews shared stable and peaceful relations, softened by over a millennium of coexistence and often shared adversities.

Al-Quds is the Arabic name for the ancient city of Jerusalem1, which bears witness to a rich tapestry of multiculturalism and religious tolerance within its ancient walls. Mosques, synagogues, and churches representing various sects, such as Orthodox, Catholic, Armenian, Maronite, Protestant, and many more coexisted responsibly. The Mosque of Omar, built on the site of Caliph Umar's first prayer after capturing the city from the Byzantine Empire, exemplifies the true spirit of coexistence. Sophronius, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, invited Umar to pray within the walls of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but he refused to endanger the church and opted to pray outside its walls.2 This decision aimed at fostering coexistence, allowing both the church and mosque to peacefully inhabit the ancient city walls.

For 400 years, from 1516 to 1917, Jerusalem was under Ottoman rule. This period saw the flourishing of a diverse society marked by religious tolerance. The Ottomans, influenced by other Islamic empires, implemented a millet system allowing different religious courts to operate based on their beliefs within their territories. The millet system is often lauded as an example of cultural tolerance, and considered as an early form of institutionalized cultural recognition. However, the influx of Western ideas of nationalism in the 19th century broke down the lenient judicial system and led to epochs of greater minority repression.3 This weakened the empire internally, causing its eventual destruction and the entrance of French and British armies into the Middle East.

In 1799, Napoleon’s troops were camped outside of the Ottoman-controlled, walled city of Acre. There, he attempted to win the sympathy of European Jews through a written proclamation calling them the “rightful heirs of Palestine.” It was here that the ideas of Zionism were first experimented with, over a century before they would be implemented by the British. Napoleon was defeated in his campaign for Egypt and Syria and returned to France with his empty promise. While the goals of the French general were not immediately implemented, his ideas of nations, ethnicities, and territories would soon sweep the European continent with nationalist revolutions signaling a paradigm shift in Western ideologies of state, land, and identity.

By 1840, the British returned to Palestine with the intention of challenging Egyptian Sultan Mohammad Ali who had liberated Egypt from French occupation. Ali had been an ally and fought for the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II, but later turned against him and won territory in Syria, Sudan, and Greece. To halt his expansion, the British intended to convince the Ottomans to back the plans of a Jewish state as a buffer against Egypt bordering the Sinai peninsula. Exerting influence over the weakening Ottoman Empire, British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston wrote to his ambassador in Constantinople urging him to convince the Sultan and his entourage to open Palestine for the immigration of Jews. At that time, there were estimated to be no more than 3,000 Jews in Ottoman-controlled Palestine.

We still live under an ideological regime derived from the bizarre categorizations of human beings developed at the peak of colonial conquest in 19th and early 20th century Europe. It was under the context of burgeoning nationalisms that tied ethnicity to land claims in which various 19th-century ideologies were formed in Europe. Other than fascism which would erupt in the wars of the early 20th century, Zionism was coined and emerged in the aftermath of the European identity crisis of the post-Napoleonic political landscape.

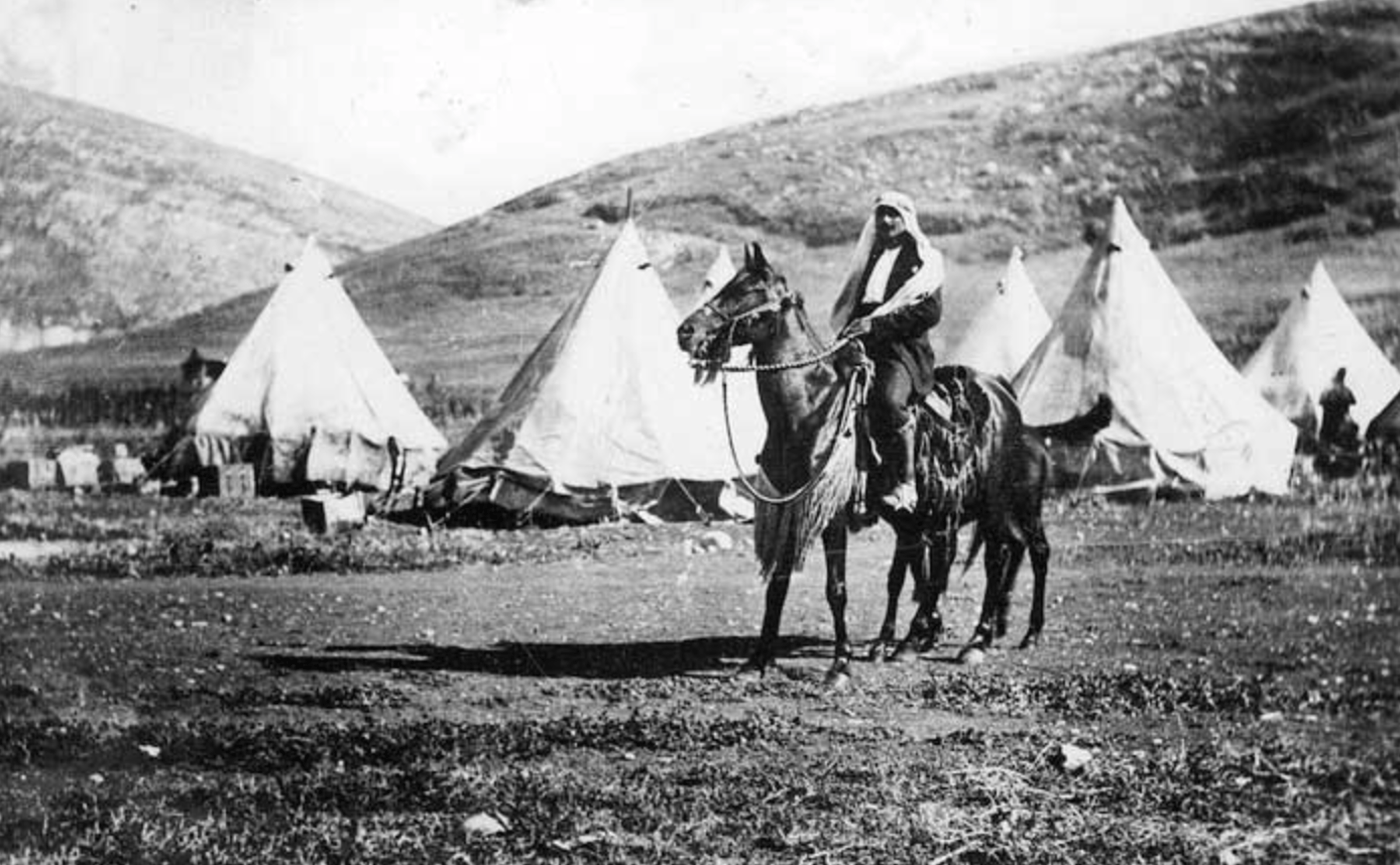

During the revolt of Egyptian ruler Mohammed Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha against Ottoman rule, Palestinians revolted against conscription rules. In the moments of repression by the occupying force, Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike faced the same enemy and began to form a common Palestinian identity rooted in the land against outside forces.

On 25 April 1834, a peasants’ revolt in Palestine and parts of what is now Jordan was sparked when Egyptian Ottoman authorities announced plans to conscript men to the military and confiscate residents’ guns.

According to Khaled Safi: “peasants’ refusal to be disarmed may have been even stronger than the resistance to conscription. They had been carrying guns generation after generation, the weapons being handed down from father to son in order to protect themselves, their lands, their country, and their interests. In their view, the call for giving up their weapons did not only imply that they were being deprived of traditional power, it also wounded their dignity and pride.”

Revolt first broke out in as-Salt, Jordan, then spread through most of the historic area of Palestine, which now includes the current territory of Israel. In particular, battles against Egyptian troops occurred in towns and cities including Gaza, Safad, Nablus, Jerusalem, and Hebron. By June, most of Palestine was in the hands of the rebels.

Then, Egyptian ruler Muhammad Ali arrived with a force of 15,000 troops. He first agreed to abolish conscription and amnesty for rebels. But after the peasant forces abandoned their positions, Ali broke his promise, brought in reinforcements, and began a violent crackdown, killing thousands. While Christians and Jews had not taken part in the uprising, as they were exempt from conscription, they were not spared in the violent repression, which was especially violent against Jewish residents of Hebron.

Eventually, Ali succeeded in conquering the region, disarming the population, and introducing conscription. Over 9,000 young men were subsequently captured and conscripted.

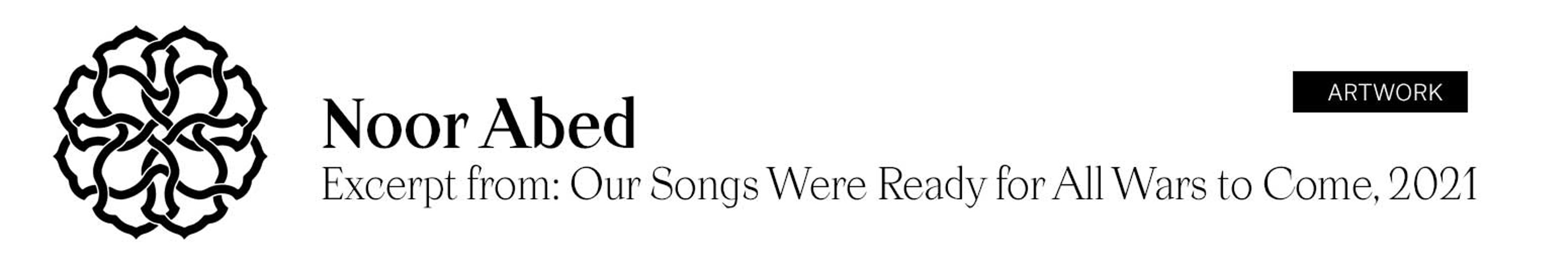

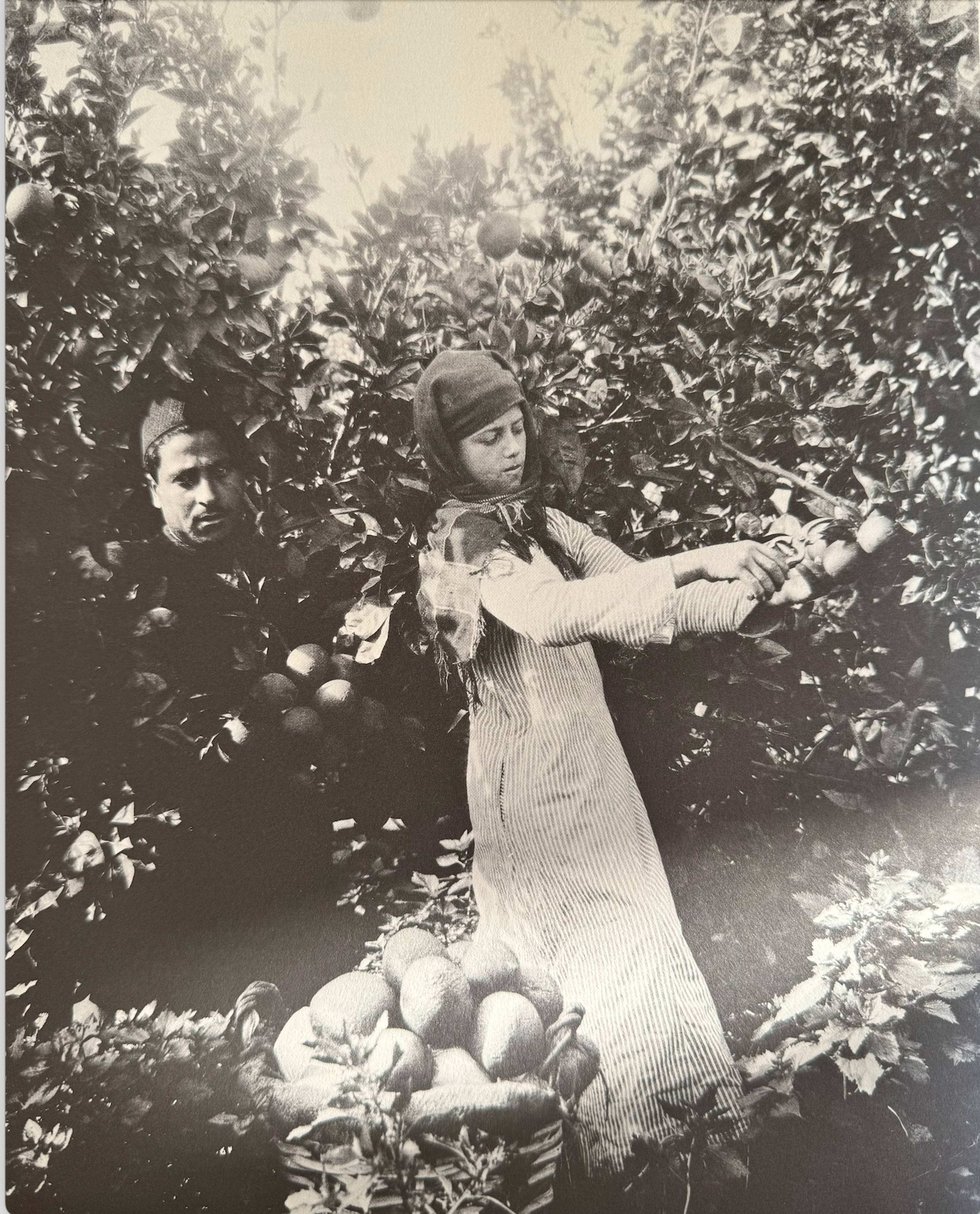

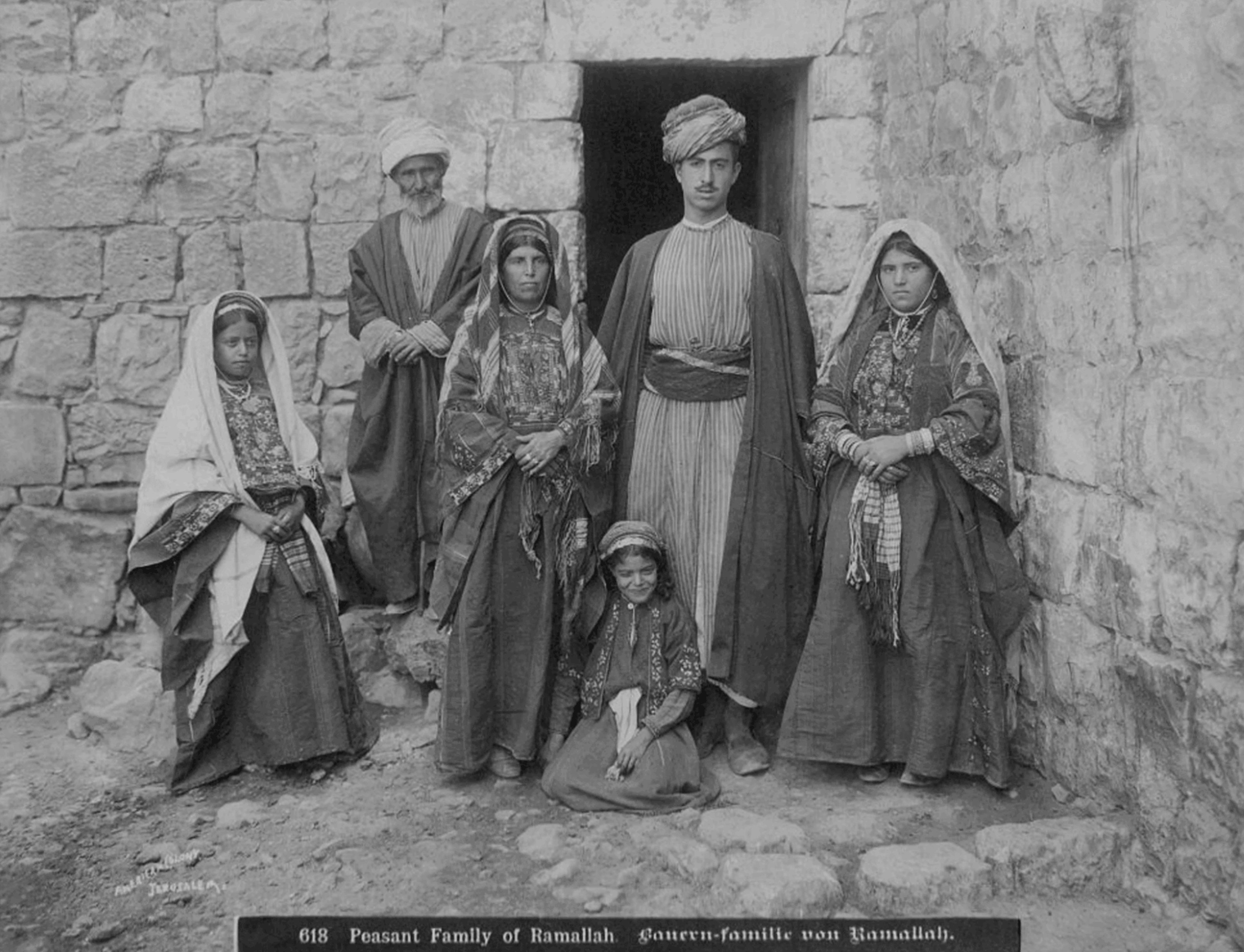

Over the course of hundreds of years of uninterrupted rule, the Palestinian people had developed a strong local identity situated within a pan-Arab geography that encompassed diverse religious and ethnic groups. Noor Abed’s practice draws upon folklore and sound archives in order to reclaim local histories that are in danger of being erased. Literary sources point to Palestine as an important site of pilgrimage as well as passage towards Mecca for pilgrims completing the Hajj. Birds, plants, and fish feature heavily in the tales which are situated in the vastly varied ecosystem nestled in the region.

Sultan Abdul Hamid II began his reign by announcing the first Ottoman constitution on December 23, 1876. The Constitution was an attempt to reconfigure the relationship between the Ottoman state and its subjects by crafting a single Ottoman political identity applied equally to all the empire's subjects. This meant that everyone, including Muslims, Jews, and Christians, regardless of their religion had the right to liberties such as freedom of press and free education. The constitution also reaffirmed the equality of all Ottoman subjects, including their right to serve in the new Chamber of Deputies.

The constitution was more than a political document; it was a proclamation of Ottoman patriotism, and it was an assertion that the empire was capable of resolving its problems and had the right to remain intact as it then existed.

It also facilitated the establishment of a General Assembly composed of two chambers: the Senate, whose members were appointed by the Sultan, and the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies, whose members were elected in the provinces.

The constitution was in effect from 1876 to 1878, in a period known as the First Constitutional Era, and from 1908 to 1922 in the Second Constitutional Era.

The first Ottoman parliament convened in two terms between March 1877 and February 1878. It consisted of two chambers: the Chamber of Commons and the Chamber of Deputies.

Yusuf Diya-uddin Pasha al-Khalidi was elected to the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies as an official representative of Jerusalem. He was the only Palestinian elected member of the first Ottoman parliament.

On February 13, 1878, the parliament was suspended indefinitely due to criticisms of incompetency over the Russo-Turkish War, but not formally abrogated by Sultan Abdul Hamid II.

Noor Abed / Still from “Our songs were ready for all wars to come” (2021)

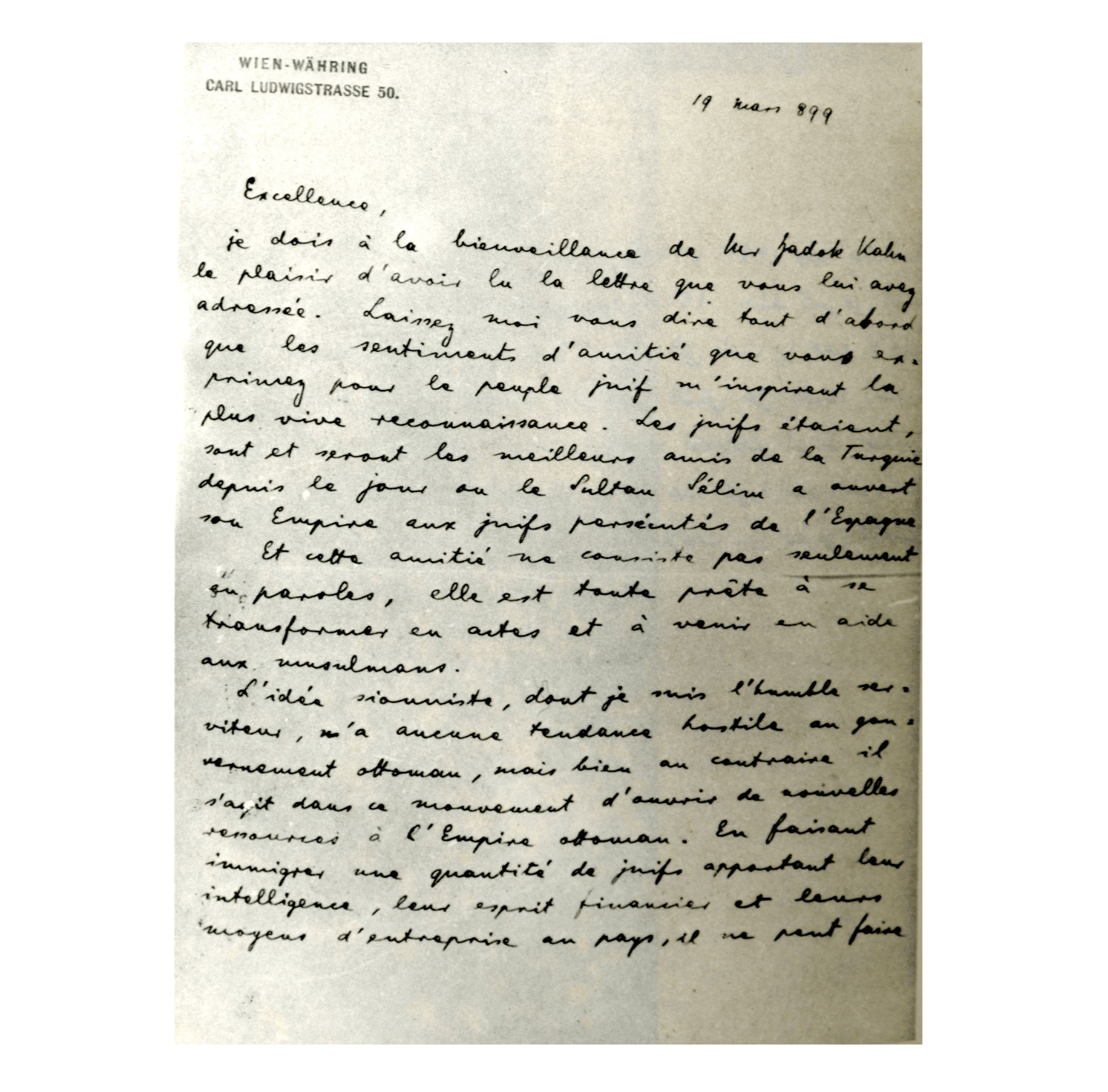

Yusuf Diya’s letter and Theodor Herzl’s response to it are well-known to historians of the period, but most of them do not seem to have reflected carefully on what was perhaps the first meaningful exchange between a leading Palestinian figure and a founder of the Zionist movement. In this excerpt from the Introduction of The Hundred Years' War on Palestine, Rashid Khalidi lays bare the colonial nature of the century-long conflict in Palestine through his own family's history.

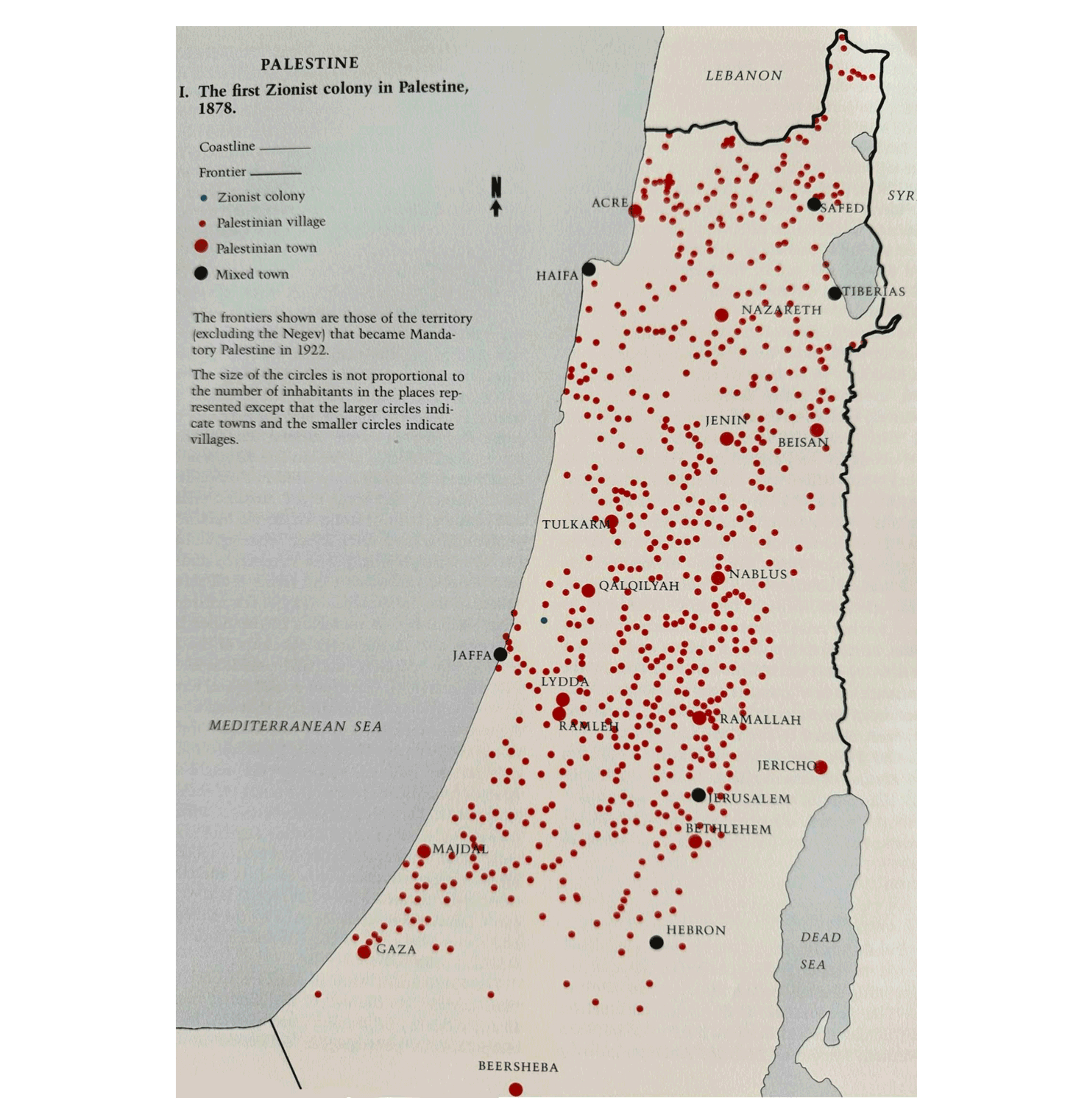

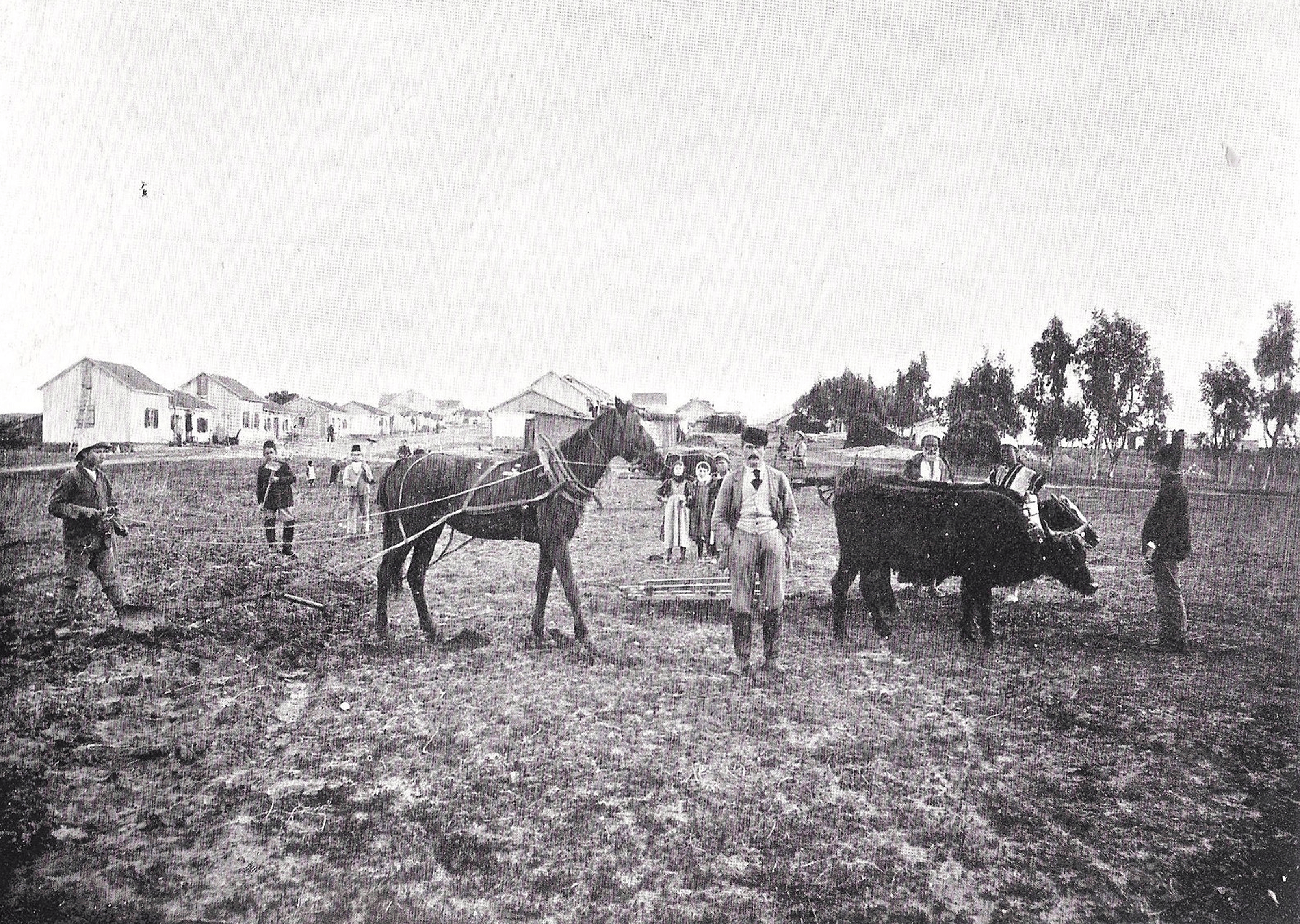

Petah Tikva (Gate of Hope) was the first Jewish agricultural settlement established in Ottoman Palestine. Its name is a reference to its original proposed location near Jericho which was denied by Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Instead, he granted the European Jews lands which were of low value in a malarial swamp. In 1880, the settlement was abandoned due to the outbreak of disease.

It was settled again in 1882, as the first Zionist settlement, by immigrants in the first wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine, most of the new villagers arrived from the Russian Empire. Funding for swamp drainage was provided by Baron Edmond de Rothschild. David Ben-Gurion lived in Petah Tikva in 1906 after emigrating from Europe.

In 1881, the assassination of Tsar Alexander II began a period of deep antisemitism and pogroms across the Russian Empire. Many Russian Jews emigrated to the United States, but a movement formed named “Lovers of Zion” whose destination was Palestine. Aware of their intentions, the Ottoman Empire wished to avoid another national problem within their empire and proclaimed: “[Jewish] immigrants will be able to settle as scattered groups throughout Turkey, excluding Palestine. They must submit to all the laws of the Empire and become Ottoman subjects.”

The context behind these prohibitions came from the recent experience of the Russo-Turkish war over Crimea when Russia had laid claim to protect all Orthodox Christians in Ottoman lands. A legitimate fear of Europe claiming protections rose in Constantinople about what would happen if European Jews were allowed to flood into Jerusalem. Furthermore, most of the Jewish people who were arriving were Russian subjects - the arch-enemy of the Ottoman Empire.

Settlers established agricultural enterprises, thanks to the massive financial contributions of wealthy European Jews, most notably Baron Edmond de Rothschild and Baron Maurice de Hirsch. De Rothschild invested more than 14 million French francs in order to establish 30 Jewish settlements. Baron Maurice de Hirsch established the Jewish Colonisation Association in London in the year 1881 investing 15 million French francs. This organization still exists today after being renamed the Jewish Charitable Association.

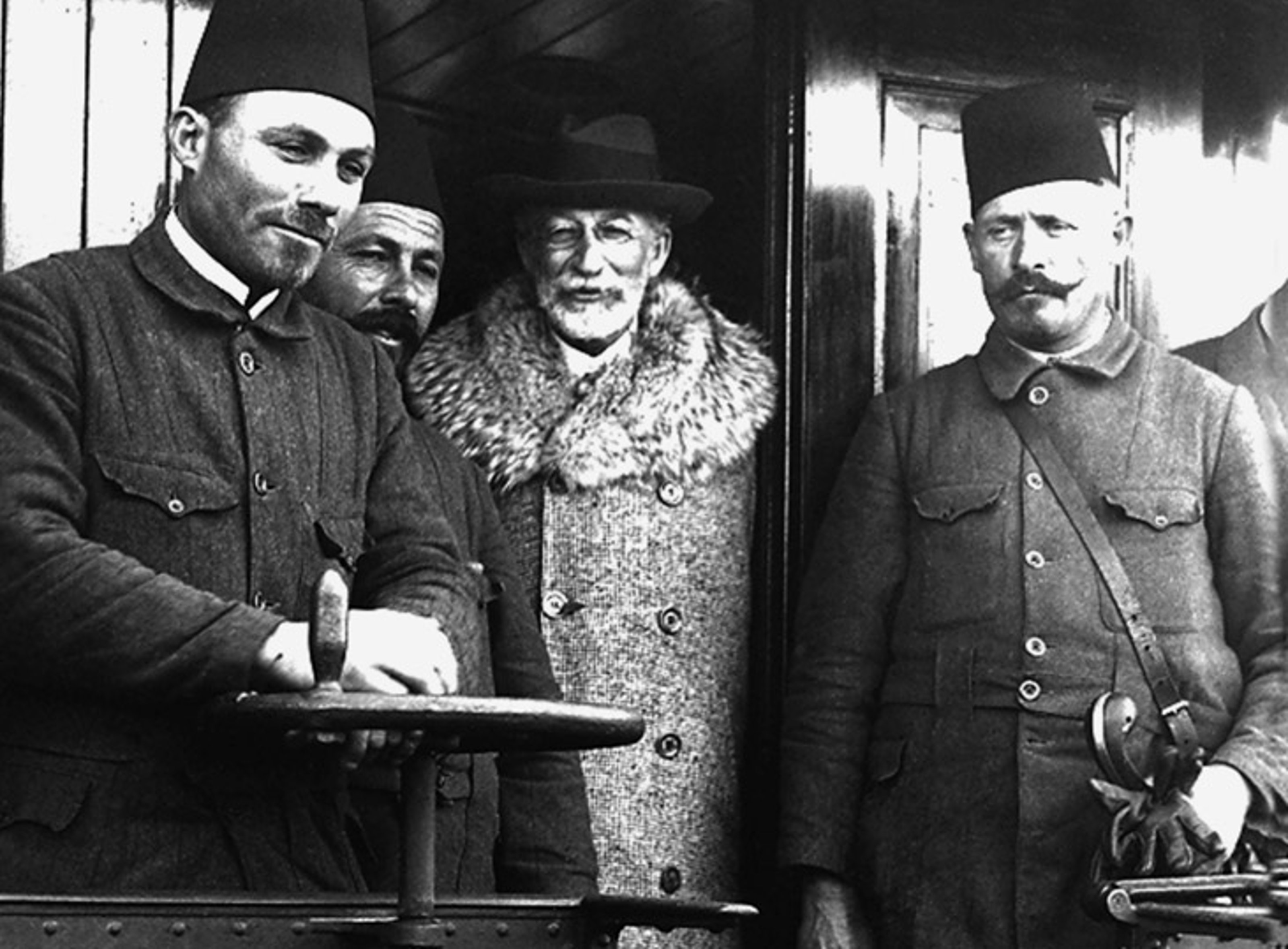

Baron de Rothschild undertook five journeys to Palestine, each marked by the accompaniment of experts and specialized equipment aimed at aiding the colonies and fostering the growth of health, education, and agriculture. His inaugural journey, at the age of 42 in 1887, was executed incognito to evade Ottoman notice.

The first wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine was called the “First Aliyah” in which roughly 25,000 Jewish immigrants, mainly from Eastern Europe, settled in the lands within 20 years. The term aliyah is one of the basic tenets of Zionism meaning to “ascend” to the land that they consider Israel. Yerida, the opposite of aliyah, is the practice of emigrating from Israel; it means “the descent.” This vocabulary is important in understanding the aims and ideology of Zionism which considers this a metaphysical uplifting. The term aliyah was widely popularized by Arthur Ruppin, a German Zionist and pseudoscientist who proposed a Jewish race theory.

In 1882, it had already been declared that only pilgrims were allowed to go to Palestine. There were two main purposes of the Ottoman government behind the formulation of a restrictive policy for the Zionist movement in Palestine. First, the foreign Jews had been able to enter and settle in Ottoman Palestine through the protection of the European powers under the capitulations. Therefore, by the restrictions, the Ottoman government was also willing to prevent the foreign powers from interfering in its domestic affairs and the foreign subjects from deriving benefits from the capitulations.

Secondly, the Ottomans wanted to avoid the budding Jewish nationalism in the Ottoman land, fearing that it might turn into a larger movement for a separate Jewish state in Ottoman territories

The explicit exclusion of Palestine is notable in that it indicates an early awareness among the Ottomans of the threat posed by the Zionists and their European sponsors.

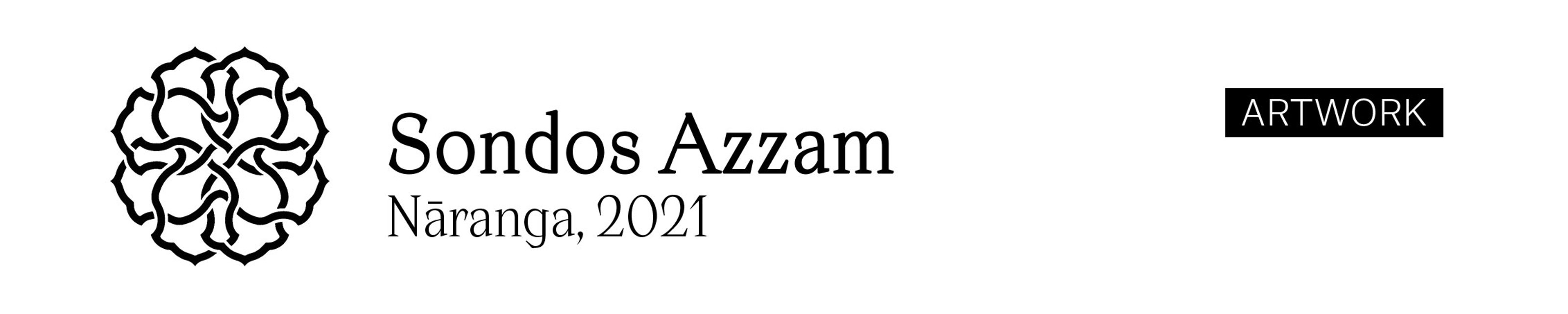

Sondos Azzam’s multi-sensory dining experience, Nāranga, explores the collective memory of the Jaffa orange through a five-course meal. With each dish, the diner considers one of the fruit’s sensorial layers and recontextualizes it. It all begins with peeling an orange wrapped in wax paper, onto which excerpts from Ghassan Kanafani’s “The Land of the Sad Oranges” are imprinted. The project thus finds an anchor in history: Jaffa’s role as a hub for orange production until 1948, the confiscation of Palestinian-owned orange groves during the Nakba, and the fruit’s later subsumption into the Israeli national identity.

Today the Jaffa orange is the agricultural product that is most closely associated with Israeli production, yet Palestinian expertise had already developed the Jaffa orange before the Zionist colonization of Palestine got underway. In 1886, the American consul in Jerusalem, Henry Gillman, writing to Assistant Secretary of State J. D. Porter, called attention to the excellent quality of the Jaffa orange and the superior grafting techniques of Palestinian citrus farmers: "I am particular in giving the details of this simple method of propagating this valuable fruit," he reported to Washington, "as I believe it might be adopted with advantage in Florida." It was not until the end of the Mandate that Jewish production managed to catch up with Palestinian production levels. Even then, however, Palestinian citrus production remained slightly ahead, both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Towards the end of 1882, Isaac Fernandez, the President of the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Constantinople, was told that the Ottoman Government feared the possibility of nurturing a national problem within the Empire. Ottoman ministers informed Fernandez that they were determined to 'firmly resist the immigration of Jews into Syria and Mesopotamia, as [they] did not wish to have another nationality established in great numbers in that part of the Empire.’

A year later, the Minister of Internal Affairs and others explicitly indicated to Fernandez that they regarded Jewish colonization of Palestine as a political issue and they 'did not want, after the Bulgarian, Romanian and other questions, to have a new question on their hands.'

In 1882, the first of the six “First Aliyah” Judean colonies—which all originated from Jewish colonists purchasing land from Christians near Jaffa—was established. Rishon le Zion was amongst the three Judean colonies—Eqron and Qastin (in its first phase) being the other two—that benefited from the management and administration of French-Jewish philanthropist, Baron Edmond de Rothschild. The Rothschild administration acted as a quasi-governmental institution for the colonies, mediating deals and requests with local Ottoman authorities for the survival of the colonies. It was precisely because Rishon le Zion hosted the administration’s regional headquarters—as well as due to its proximity to Jaffa, size, and economic activity—that the colony served as the administrative and organizational center for all the Judean colonies.

In 1882, Rothschild declared: "I have done this because I have seen in you the fulfillers of Israel's dream of resurrection and of the precious ideal of us all - the sacred goal of Israel's return to the homeland of its forefathers."

Though Judean colonists mainly came from different backgrounds in Eastern Europe, the colonies eventually crystallized into a bloc. They cooperated extensively, exchanging resources, and expertise, and offering mutual support. As their presence grew, they aimed to create a contiguous Jewish territory by acquiring additional land and preventing its purchase by non-Jews. This fostered the development of a collective sociocultural identity, which launched the formation of a Jewish national community in Palestine, laying the groundwork for future Zionist aspirations in the region.

In March of 1884, the Ottoman council, composed of the Ministries of Internal and Foreign Affairs, decided to ban entry to Palestine to Jewish businessmen, citing that the capitulations that allowed Europeans to trade freely within the Ottoman Empire only applied to areas deemed suitable for trade. The council did not consider Palestine as such an area.

As a result, only Jewish pilgrims were permitted to enter Palestine and they were required to have their passports properly approved by Ottoman Consuls abroad. Upon arrival, they were obliged to provide a deposit ensuring their departure within thirty days. For the restrictions to be effective, they needed to be accepted by the foreign powers, whose nationals would be affected by them.

Nathan Birnbaum was an Austrian-Jewish writer and theorist who first coined the term “Zionism.” His beliefs and thoughts progressed through three stages in his lifetime. In the first phase of his thinking from 1883 to 1900, he was involved with the conceptualisation of Zionism. After the turn of the century and until 1914, he turned away from Zionism and towards a form of Jewish Cultural Autonomy that advocated for Jews staying in Eastern Europe and defending their shared cultural heritage, particularly the Yiddish language. In the last part of his life, he became more religious following Orthodox Judaism and loudly opposed Zionism as heretical to the Jewish faith. Birnbaum was living in Berlin in the 1930s during the Nazi’s rise to power. He fled to the Netherlands where he published the Anti-Zionist newspaper Der Ruf ("The Call") until his death in 1937.

Aware of their discontented Empire and worried about the loyalty of their Arab subjects, the Ottoman government attempted time and time again to prevent Zionist settlement. Though it had decided, in 1888, to solely allow Jewish pilgrims to enter Palestine, strong opposition from Britain, France, and the US forced the Ottomans to yield. Thus, regulations came to apply to large groups of Jewish immigrants exclusively, however, no obstacles were to obstruct the path of individual Jews.

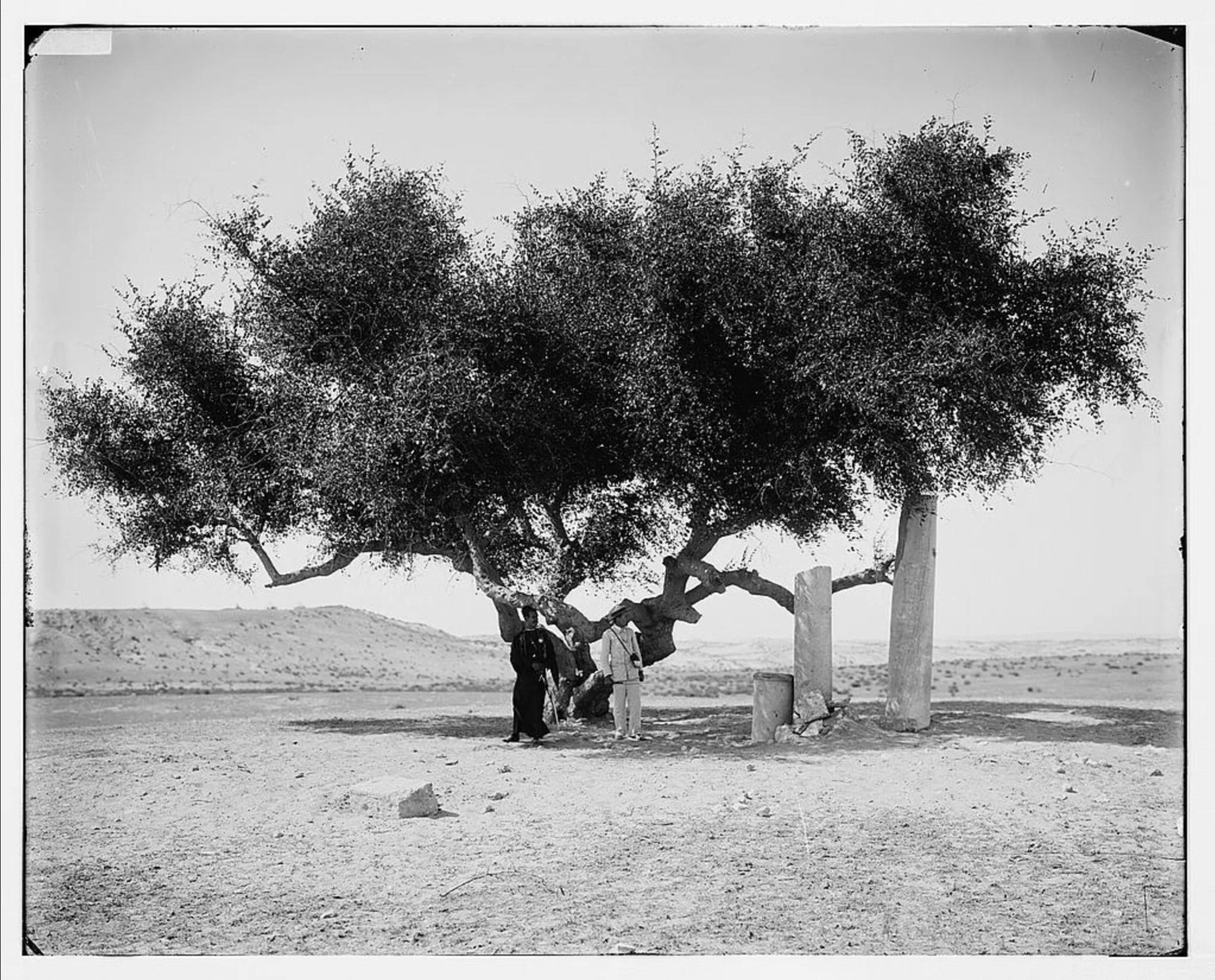

The olive tree has become a symbol of Palestine and resistance. The oldest trees in this region are believed to be 4,000 years old, predating the Roman occupation of “Palaestina.” They have been a constant companion to the people and the landscape regardless of changing rulers—they have fed and shaded villagers for millennia. Today, some of the oldest trees are in danger of being uprooted by occupation forces to build walls and settlements. Adam Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez have been photographing and documenting Palestine’s olive trees, issuing a call for their preservation in the face of the relentless advance of bulldozers.

The Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) was founded in 1891 by Baron Maurice de Hirsch in London to establish Jewish agricultural colonies globally. Initially focused on South America—transporting 150,000 Eastern European Jews to colonize Argentina by 1920—the JCA extended its support to Jewish settlements in Palestine in 1896. By 1899, the JCA assumed management of nine struggling colonies previously supported by Baron Edmond de Rothschild, which had, up until that point, failed to become self-supporting and settler-owned.

Despite internal disagreements, the partnership lasted until after World War I, with the Palestine Commission overseeing the colonies' management, and Baron de Rothschild providing financial support. Rothschild later established the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association in 1924, acquiring more land in Palestine, creating settlements, and supporting various communities, including winemaking businesses and kibbutzim.

The Ottoman government bans the sale of miri land (private usufruct State land) to both Ottoman and non-Ottoman Jews. The decision was later retracted, after complaints by European powers—giving Jews legally residing in Palestine the right to buy land.

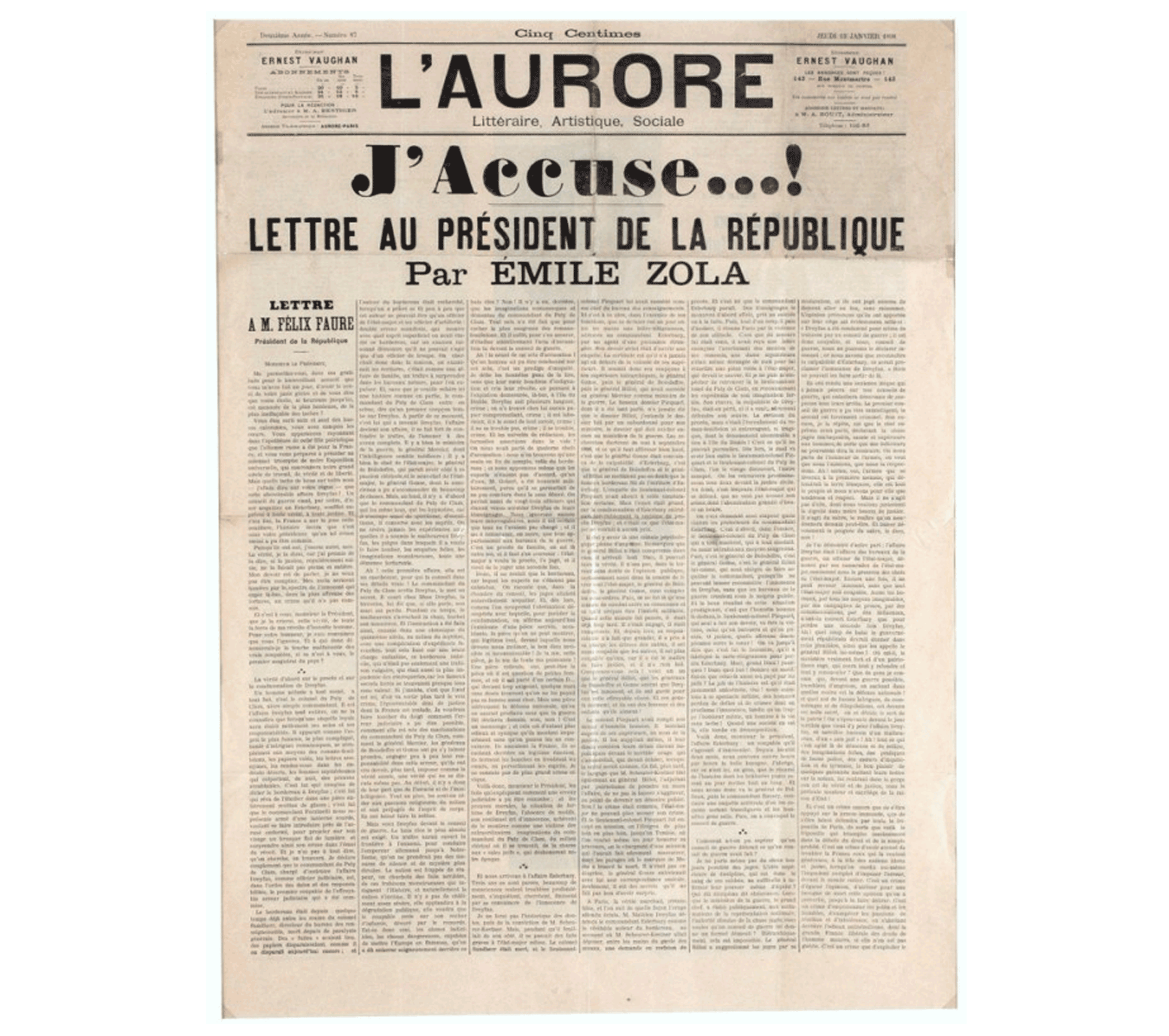

In 1894, a French officer of Jewish origin, Alfred Dreyfus, was falsely accused of passing military secrets to the German Empire, specifically regarding French artillery to the German military attaché in Paris. He was targeted primarily because he was Jewish, and the prevailing anti-Semitic sentiment in French society at the time fueled his wrongful conviction. The accusation led to his wrongful conviction for espionage and treason.

Given the unsubstantiated nature of the allegations and the fact that they were motivated by anti-Semitism, the “Affair” exposed deep-seated anti-Semitism within French society and institutions and sparked a major public debate over issues of justice, nationalism, and religious prejudice. It ultimately resulted in Émile Zola’s famous open letter to the French government, titled "J’Accuse…!." In the letter, Zola publicly accused the French government and military of anti-Semitism and of wrongfully convicting Alfred Dreyfus. Zola's letter was a powerful denunciation of the injustice surrounding the Dreyfus Affair and played a significant role in bringing attention to the case both nationally and internationally. It ignited public debate, galvanized supporters of Dreyfus, and ultimately contributed to the eventual exoneration of Dreyfus and the reexamination of the case.

The profoundly pessimistic picture of French anti-Semitism that the affair painted convinced Herzl that assimilation into European society was pointless. Though this is now questioned by scholars, Herzl claimed that The Dreyfus Affair bore his advocacy for the founding of a Jewish state.

In 1894, Herzl, an Austro-Hungarian journalist, famously published The Jewish State (Der Judenstaat), a seminal text of early Zionism advocating for an independent Jewish state as a solution to the “Jewish question.” Anchored in nineteenth-century European political maneuvers—which included the notion that European governments held sovereignty over non-European colonies—and conscious of the lack of uninhabited territories to be had, the pamphlet emphasized the need for a European power to award Zionists a charter to establish a Jewish state under its protection.

Herzl envisioned gradual Jewish migration to establish the state, describing his plan as a colonial scheme. The book contemplated Palestine or Argentina as potential locations for the Jewish state, considering pragmatic benefits rather than solely religious claims. In line with Herzl's guidance, Max Nordau, his associate, sent two rabbis to Palestine to evaluate the feasibility of a Jewish state. Their resulting report depicted the situation as follows: "The bride is lovely, but she is already wedded to another."

Herzl offered to pay £20 million, which is around $2.2 billion in today's currency, to the Ottoman Sultan to issue a charter for Jews to colonize Palestine. The money would have relieved around 20 percent of the Ottomans’ debt burden. It has been reported that Herzel exclaimed that "without the help of the Zionists, the Turkish economy would not stand a chance of recovery."

Sultan Abdul Hamid II refused the offer outright in 1896, saying, "if Mr Herzl is as much your friend as you are mine, then advise him not to take another step in this matter. I cannot sell even a foot of land, for it does not belong to me but to my people. My people have won this Empire by fighting for it with their blood and have fertilized it with their blood. We will again cover it with our blood before we allow it to be wrested away from us."

The First Zionist Congress, convening in Basel, Switzerland establishes The World Zionist Organization (WZO) and issues the Basel Program, the first manifesto of the Zionist movement, which stated: “Zionism aims at establishing for the Jewish people a publicly and legally assured home in Palestine.”

In response to the First Zionist Congress, Abdul Hamid II initiated a policy of sending members of his own palace staff to govern the province of Jerusalem.

Having fought Jewish immigration and land purchases since the early 1880s, the Mufti of Jerusalem, Muhammad Taher al-Husseini, presides over a new commission that scrutinizes applications for the transfer of land in the Sanjaq of Jerusalem and succeeds in stopping all purchases by Jews from 1897 to 1901.

Cairo journal al-Manar warns that Zionism aims to take possession of Palestine.

In his 1899 letter to Herzl, Yusuf Dia Pasha al-Khalidi, Mayor of Jerusalem, agreed that the Jewish people had the right to find refuge. Yet he also warned about the dangers he foresaw, highlighting the presence of a Palestinian population that would never accept conquest, and the crucial role of Palestine in the Ottoman Empire—pleading with Herzl to leave Palestine alone.

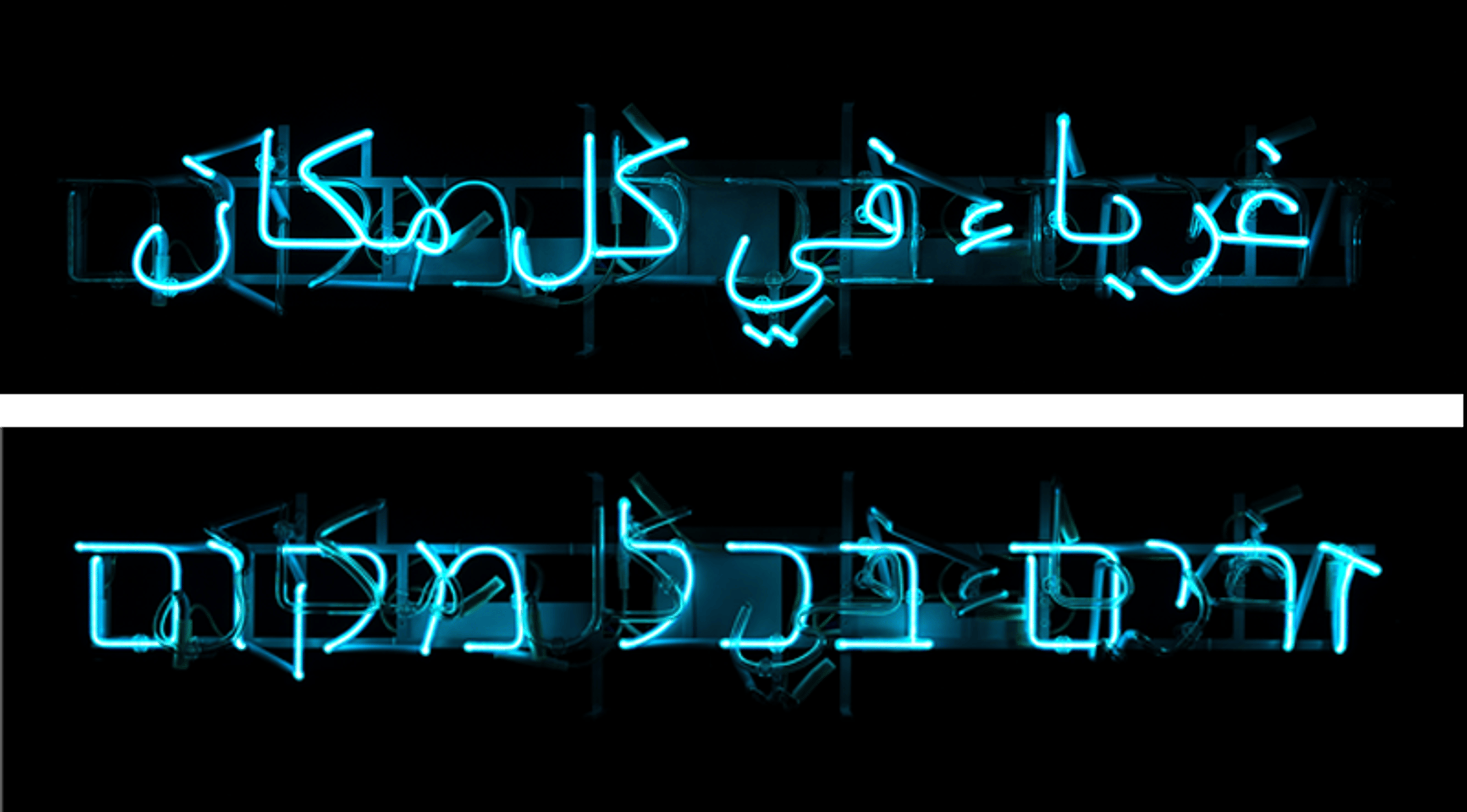

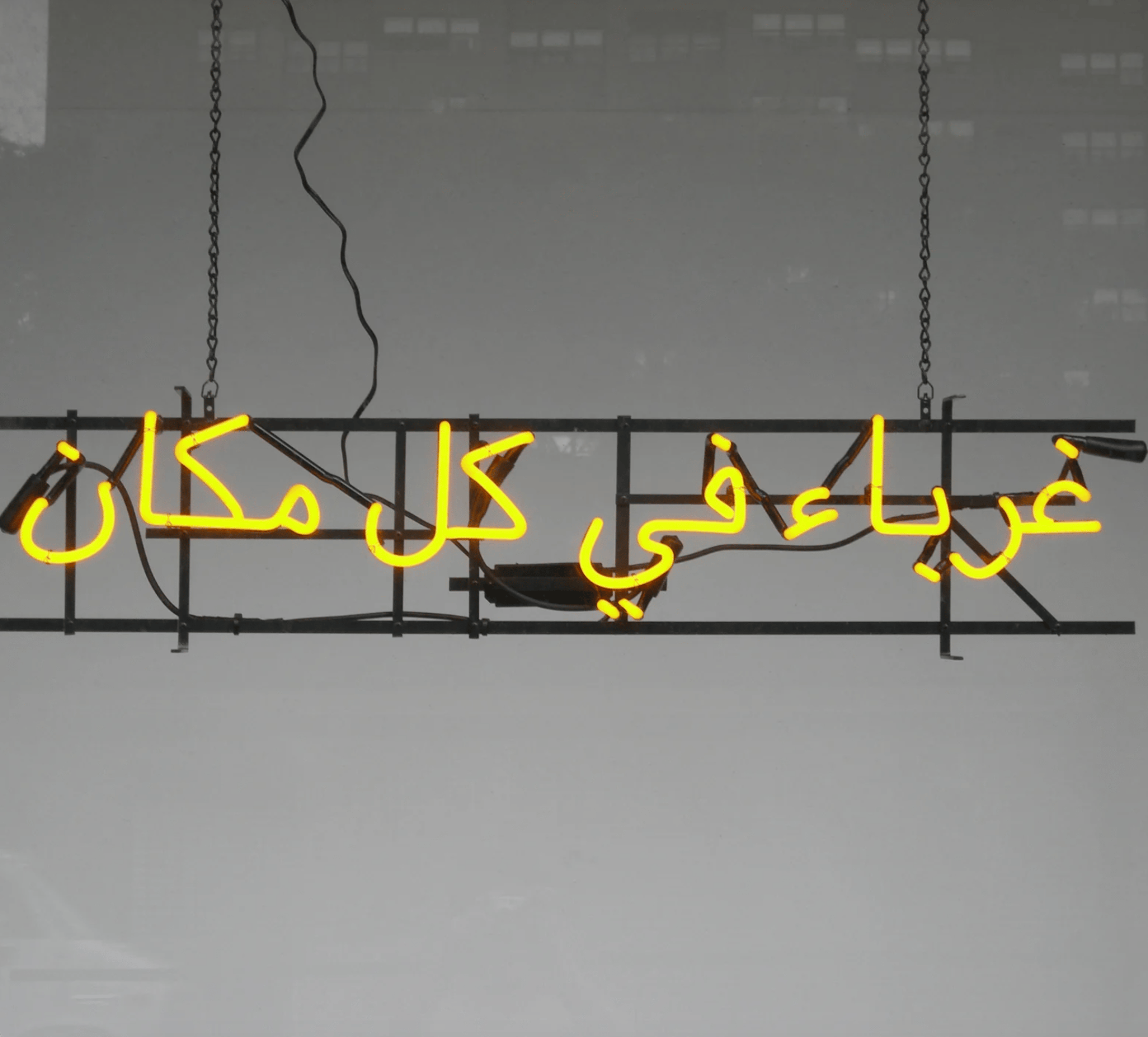

Foreigners Everywhere (Arabic/Hebrew) 2010, is a work that conceptually confronts the identity of the foreigner with that of the displaced. The work is originally appropriated from an anarchist collective from Turin named Stranieri Ovunque and uses the ambiguity and suggestiveness in this name in different languages and spaces to reflect changing contexts. Despite political removals of special taxes for Jewish people, European antisemitism in the 19th century paradoxically saw European Jewish populations as foreign to the homogenous and patriotic nation-state. It was Napoleon who first pointed to Palestine as their origin and home, and newly conceptualised political unity tied ideas of blood to soil. Zionism thus emerged as a solution, conforming Jewish identity to the same ideas that would go on to create 20th century fascist movements. From one mass-displacement to another, the status of the foreigner was transferred onto the Palestinian population—a people who had nothing to do with the suffering of European Jews—expelled from their lands into exile.

"The Zionist idea, of which I am the humble servant, has no hostile tendency toward the Ottoman Government, but quite to the contrary this movement is concerned with opening up new resources for the Ottoman Empire. In allowing immigration to a number of Jews bringing their intelligence, their financial acumen and their means of enterprise to the country, no one can doubt that the well-being of the entire country would be the happy result. It is necessary to understand this and make it known to everybody."

In Theodor Herzl's reply to al-Khalidi—perhaps the first Zionist response to objections over the occupation of Palestine—he argued, in a staple argument of the Zionist movement, that Jewish immigration would benefit indigenous Palestinians, bringing intelligence and wealth to the region.

"You see another difficulty, Excellency, in the existence of the non-Jewish population in Palestine. But who would think of sending them away?"

In response to al-Khalidi's apprehensions regarding the non-Jewish majority population of Palestine, Herzl retorted with this rhetorical question, and cryptically concluded, "If he (the Ottoman Sultan) will not accept it, we will search and, believe me, we will find elsewhere what we need."

In 1901, another attempt to curb Jewish immigration to Palestine was made. The laws established in 1881 against the settlement of Jews had been largely inefficient due to the capitulations. Countries such as France argued that French Jews had rights and could therefore settle in Palestine according to the rights granted to all French citizens. The new edict also failed. It was not until 8 September 1914 that the Ottoman Empire abrogated the laws of capitulations, ending the centuries-long treaties.

The 5th Zionist Congress establishes the Keren Kayemeth Leisrael (Jewish National Fund) to raise funds for land purchase in Palestine, opens a branch of the Jewish Colonial Trust in Jaffa, and approves of a program focusing on developing Hebrew culture.

The fund still exists to this day and receives large sums of money from Zionist communities in the USA with all donations being tax-deductible. The organization aims to expand Jewish populations and settle the extremities of what is today considered Israel. The About Us page states that “Israel’s population cannot remain concentrated on a vulnerable coastal plain, and a vibrant north and south should be attractive new frontiers for Israeli families,” employing colonial terminology such as “frontiers” and pledging up to 40% of its income to promoting activities such as “North American Aliyah.”

The second wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine (which lasts until 1914) consists of around 40,000 immigrants, many of whom have a strong ideological commitment to Zionism and call for the "conquest of the land" and the "conquest of labor." This anti-Arab attitude, which expresses itself in the expulsion of Palestinian fellahin from the settlements in which they work, will aggravate the disputes in Palestine between Jewish colonies and neighboring Arab rural communities.

Theodor Herzl dies.

Claire Fontaine / Foreigners Everywhere (Arabic), 2005

Directions For a Possible Connected Manner to Celebrate the Listening Of “US & WE”

You and a minimum of 2 more people get together.

The space/room has, at least, two speaker stereo system.

You have something ready to drink. If Alcoholic, let it be a spirit.

You have something ready to eat. Anything ‘bread’ is recommended.

You turn off all the lights.

You toast. You drink.

You internally invoke your gratitude awareness. You break the bread. You eat.

You get comfortable.

You press play.

Together, you listen.

Once finished, silence is a suggestion; a discussion a possibility; a 50 second group hug a recommendation.

Be.

WE.iS

This artwork was on view for a limited time as part of the exhibition ‘Falastin.’ It may be back in the future.

The Ottoman governor of Jerusalem issues a report that describes how Zionist immigration and land acquisition evade the regulations in force.

Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann visits Palestine. He is later credited with bringing about the Balfour Declaration. Charles Dreyfus had introduced Weizmann to Lord Balfour during a visit to London in 1905.

Carrying out a resolution passed during the 8th Zionist Congress in July 1907, the Zionist Organization opened an office in Jaffa. This Palestine-based office focused on procuring land and founding Jewish settlements, serving as a hub for various colonization efforts initiated by philanthropic groups or immigrant associations.

Arthur Ruppin, a German Zionist proponent of pseudoscientific race theory and one of the founders of the city of Tel Aviv, emigrated to Palestine. Ruppin believed that in order to achieve Zionist intentions, the “purity” of the Jewish race would need to be preserved. These theories were influenced by the same racist sources that contributed to Nazi race theory. Ruppin argued against the immigration of Ethiopian and Yemeni Jews.

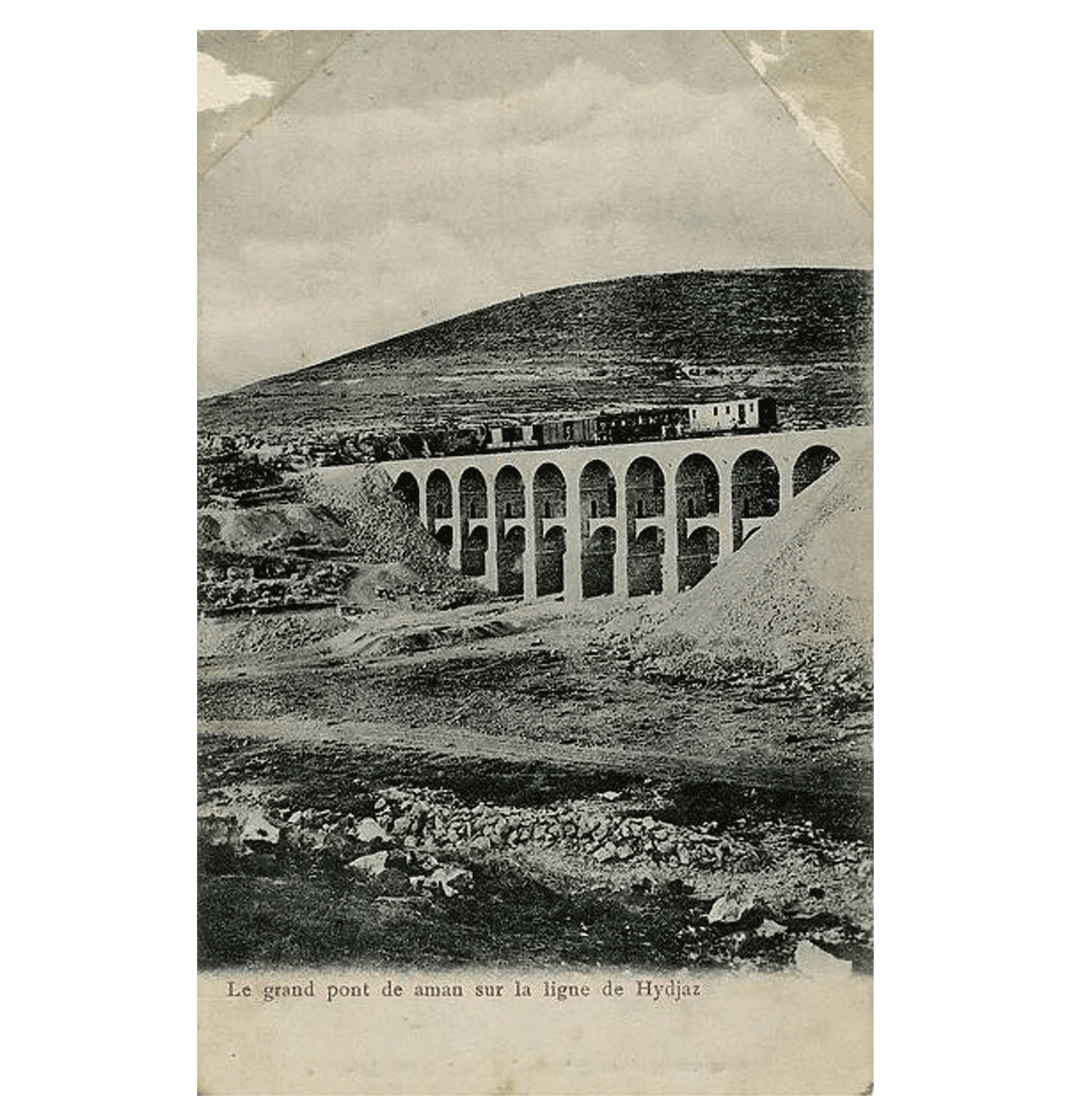

During the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, the Hijaz-Palestine Railway project emerged as a way to link the holy sites in the Hijaz to Istanbul, easing the journey for Muslim pilgrims. The Sultan presented this railway project as an important symbol in confronting Europe and its influence in the Middle East, a region that was still largely subordinate to the authority of the Ottoman Empire. It would also help the Sultan tighten his grip on distant Ottoman states far from the center of his rule in Istanbul and send military forces should a rebellion or revolution need quelling.

The railway was successful in developing cities such as Haifa from villages to bustling centers of trade that connected Mediterranean ports to inland routes.

The investments that poured into developing this region demonstrate the enormous potential that existed in the multicultural climate fostered by Ottoman policy. The rail line was eventually halted by Col. T.E. Lawrence in the battles waged by Britain against Ottoman forces.

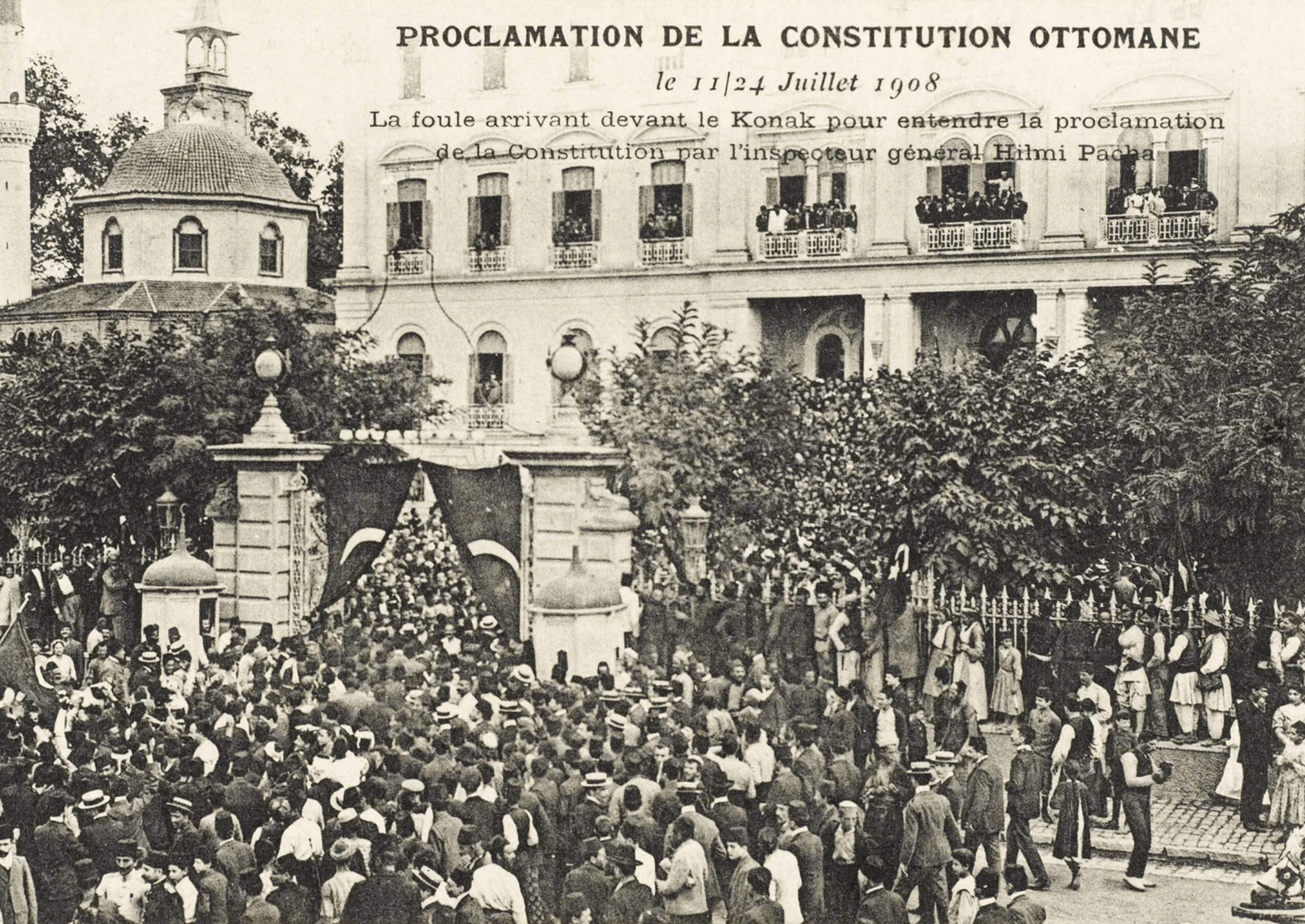

Army officers loyal to the Committee of Union and Progress take control of Constantinople and force Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the 1876 constitution and call for parliamentary elections. The revolution helped to establish the Second Constitutional Era, ensuring a multi-party democracy for the first time in the country's history.

Both Arabs and Turks participated in the "Young Turks" movement but, as World War I approached, tensions between the two peoples mounted.

In 1905, prominent Palestinian journalist, Najib Nassar, began campaigning against Zionism by publishing articles in the newspapers al-Mokattam in Cairo and Lisan al-Hal in Beirut. After the Ottoman constitution was restored, Nassar sold his property and purchased a printing press in Beirut. In 1908, he established the newspaper al-Karmel in Haifa, Palestine, which was published twice weekly and named after Mount Carmel in the Haifa district. Nassar consistently highlighted the Zionist threat to Palestinians and, as such, due to a Zionist campaign against him, his newspaper was shut down by Ottoman authorities for two months in June 1909. In 1910, The Jewish Chronicle featured an article by its correspondent in Palestine about a legal case involving Nassar. The correspondent reported: “The lawsuit against Nassar was attended by a numerous audience which after his acquittal carried him triumphantly in a demonstration hostile to the Jews.”

The Bar Giora Group was created in 1907 as an underground organization that met in the Kfar Tavor colony in the Tiberius subdistrict. The founders decided to establish themselves publicly and to merge into a new organization named Hashomer (the "Watchman"). This paramilitary formation was founded by Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and David Ben-Gurion, who would later go on to become Israel’s first prime minister. The group’s original slogan was “Judaea was lost by blood and fire and will rise again by blood and fire.” Its purpose continues to be to guard Jewish settlements in Palestine and provide training for an Israeli fighting force.

With the approval of the Jewish Colonization Association, the new organization applied for a license to form a unit of 10 armed Jewish guards. Tiberias authorities granted the license; it includes the provision to increase the size of the unit, if necessary. Israeli historians consider Hashomer as the nucleus of the Haganah and the Israeli army (IDF).

The ongoing project Uncertain Times covers the last days of the Ottoman Empire and the beginning of the French and British Mandates in Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine from 1913 to 1920. Lamia Joreige’s interest in this period is in the uncertainty about the region’s future which led to various speculations and alternatives to the historical timeline that played out to this day. It was a moment of rupture and fragmentation that led to the geographic, social, and political transformation of the region that dictates our present.

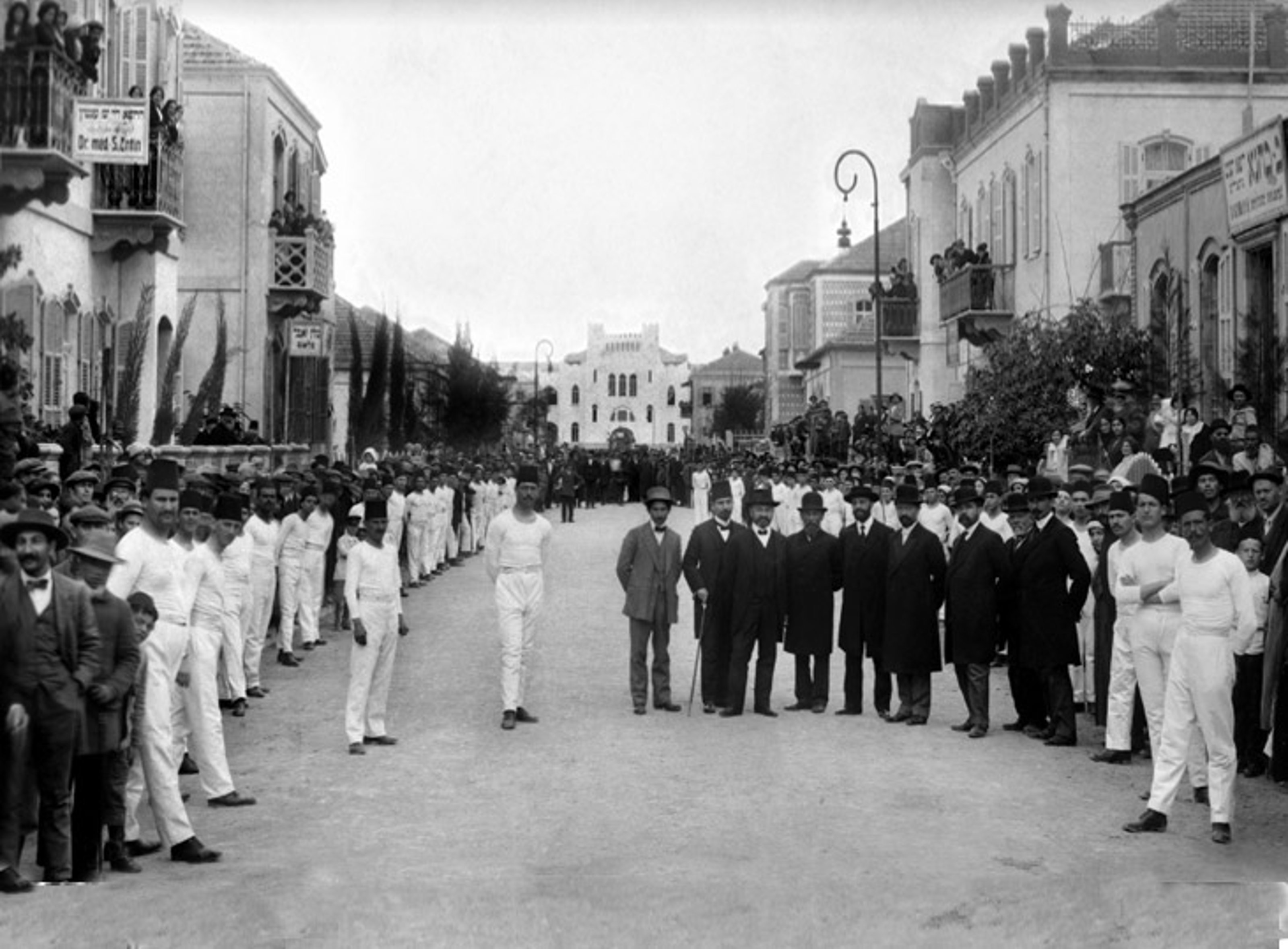

The initial parcels of land upon which Tel Aviv was established north of Jaffa were auctioned off in 1909, with the plots purchased from the Bedouin Tribes.

On April 11, 1909, 66 Jewish families convened on a sand dune to divide land through a lottery system using seashells. Organized by Akiva Aryeh Weiss, president of the building society, the lottery utilized 120 seashells collected from the beach, equally divided between white and grey shells. Names were inscribed on the white shells, while plot numbers were assigned to the grey ones. A boy and a girl were entrusted with the responsibility of drawing both names and numbers.

Tel Aviv, derived from the Hebrew translation of Theodor Herzl’s 1902 novel "Altneuland" ("Old New Land"), was coined by Nahum Sokolow. The name originates from a Mesopotamian site near Babylon mentioned in Ezekiel, which Sokolow associated with the Jewish people's return to their ancestral land.

The period spanning the end of 1910 to the first half of 1911 marked a significant shift in the opposition to Zionism in Palestine and neighboring Arab regions. Within this relatively short timeframe, key events unfolded, drawing the participation of Arab journalists, notables, and officers in anti-Zionist activities. Criticism of Zionism surged in the Arabic press during this period, reflecting a notable change in the attitudes of the educated Arab public toward Jewish land acquisitions, immigration, and the Zionist movement.

Arab deputies from Jerusalem, Beirut, and Damascus lobby in the Ottoman Parliament for legislation against Zionist mass immigration to Palestine.

In a telegram to Constantinople, 150 Palestinians from Jaffa demand measures against Zionist mass immigration and land acquisition.

Two Jerusalem deputies open the first full-scale debate in the Ottoman Parliament on Zionism, charging that the Zionist aim is to create a Jewish state in Palestine.

World War I breaks out, and it quickly leads to a series of events that affect the future of the Ottoman Empire. In September, the Ottomans decide to abolish capitulations that once afforded European powers special status within the Empire. In November, they officially enter the war on the German side. In December, the British annex Cyprus and declare Egypt a protectorate. In January 1915, the Ottomans occupy the Sinai peninsula. By February, the Gallipoli campaign begins to put Ottoman lands within the apex of the imperial battlefield of the war.

I am assured that the solution of the problem of Palestine which would be the most welcome to the leaders and supporters of the Zionist movement throughout the world would be the annexation of the country to the British Empire. I believe that the solution would be cordially welcome also to the greater number of Jews who have not hitherto been interested in the Zionist movement. It is hoped that under British rule, facilities would be given to Jewish organizations to purchase land, to found colonies, to establish educational and religious institutions, and to spend usefully the funds that would be freely contributed for promoting the economic development of the country. It is hoped also that Jewish immigration, carefully regulated, would be given preference so that in a matter of time the Jewish people grow into a majority and settle in the land, may be conceded such a degree of self-government as the conditions of that day may justify.

Sharif Hussein of Mecca and Sir Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner in Egypt began exchanging a series of letters wherein the Government of the United Kingdom pledged to acknowledge Arab independence and territory following the war. This commitment was made in exchange for the Sharif of Mecca's support in initiating the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

The Arab Revolt against Constantinople began soon after and, later that year, Sharif Hussein was proclaimed "King of the Arab countries."

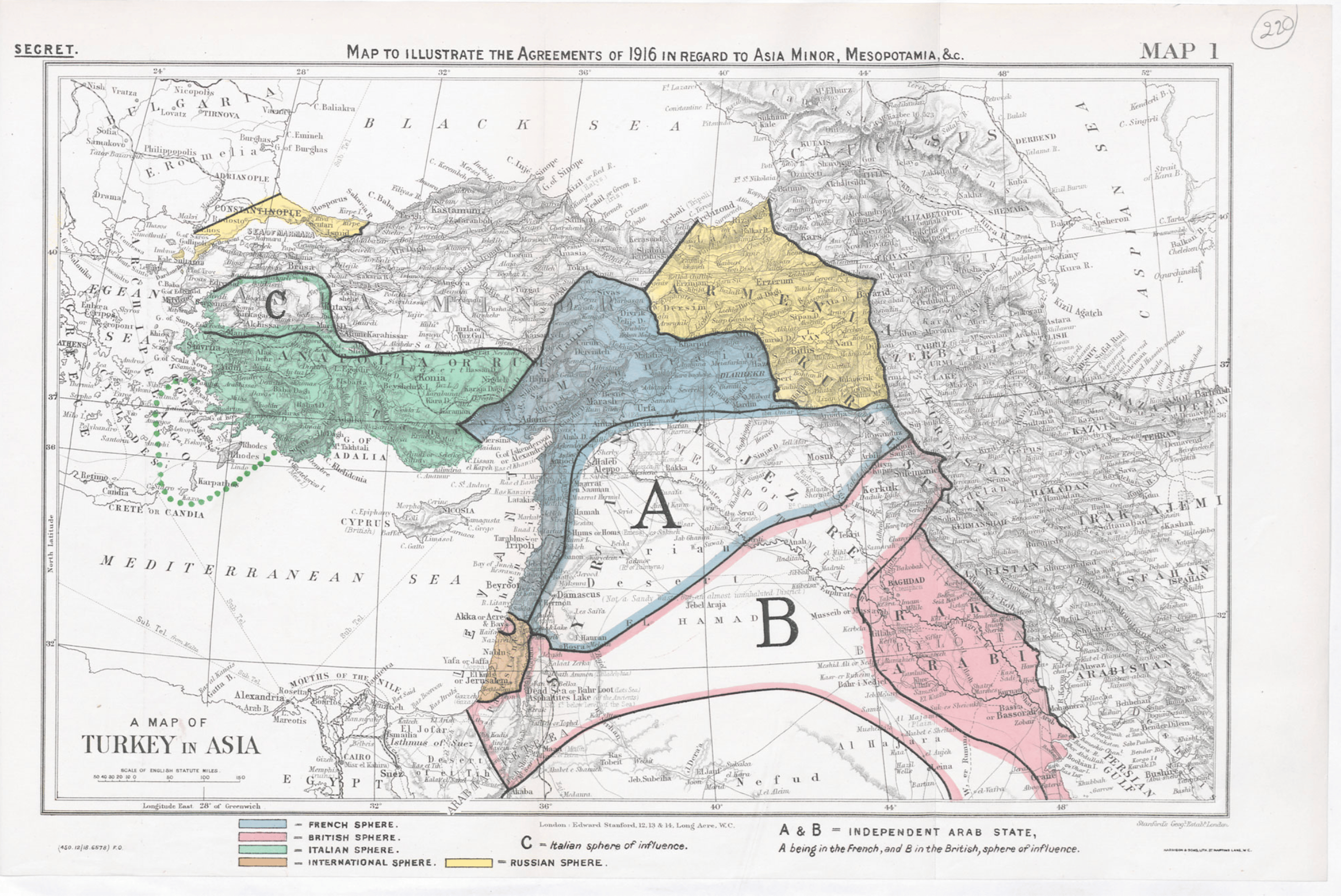

The secret agreement between Great Britain and France, with the assent of Russia, that defined their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in the declining Ottoman Empire. Named after its principal authors, Mark Sykes of the UK and François Georges-Picot of France, Sergey Dimitriyevich was also present in formulating the agreement representing Russia as the third member of the Triple Entente. Britain was awarded Palestine as its main interest was to secure safe passage to India through the Suez Canal.

Palestinians only became aware of the text of the Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1917 after the Bolsheviks overthrew the Tzar of Russia and published the signed agreement in Pravda.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 marked a significant moment in setting the stage for a series of brutally transformative events that would affect Palestinians for decades to come. With its clandestine inception and subsequent revelation to the Palestinians in 1917, the agreement acclaimed the beginning of British military administration in Palestine and furtively laid the groundwork for the establishment of the British Mandate. The subsequent incorporation of the Balfour Declaration into the Mandate further solidified the trajectory; symbolizing the triumph of Zionist influence within British political circles. This agreement isn't just a footnote in history books; it's the pivotal link connecting Palestine's past to its future. It represents decisions made in secret by oppressive forces against indigenous peoples, denying their right to self-determination and paving the way for the influx of Jewish settlers driven out of Europe by intolerance and antisemitism. The price of Europe’s expulsion of its Jewish population would soon be paid by the Palestinian people’s displacement from their ancestral lands.