The origin of the word “censor” can be traced to the office of censor established in Rome 443 BCE. While free speech and expression have always been a threat to established interests, whether in Ancient Rome, Medieval Christian Europe, through to the Soviet Socialist Republics of the twentieth century, censorship has a long, complicated history. Artists, journalists, and the intelligentsia are often the first victims of censoring bodies in times of war and conflict.

Though many governments and human rights defenders in Europe and the West rightly criticize the abuses perpetrated in new democracies and non-democratic countries alike, we should remember that the violent history of censorship and colonialism are closely intertwined. There is also a need to recognize the cruel suppression of Indigenous cultures, languages, artifacts, and non-written materials that have been appropriated or muted for centuries. This article proposes that censorship has evolved from its early days to the present, reacting to the ethical demand for the freedom of speech and operating in new, covert ways – ones which we must analyze and resist.

I have spent the better part of the last five years researching the way censorship is employed in various contexts. In 2015, I embarked to Oman where I was hired to work as a curator in a newly established contemporary art institution in Muscat. Less than 4 months later, we lost our license as an exhibiting institution before we had even opened. I was informed that this was due to conservative forces in the country that feared contemporary art. Not long after, I found myself in Istanbul, Turkey. An exhibition called Post-Peace1 curated by Katia Krupennikova was called off only hours before the scheduled vernissage, likely after the institution got wind of Kurdish content.

Censorship is like a vortex that consumes all in its wake. To this day, artists operating outside the law in countries that restrict speech and expression face serious legal and potentially violent consequences. Qualitative differences concerning punitive measures aside, one should note that censorship exists in nearly every country and every society. Powerful works of art tinker with the social engineering of the censoring body, usually from the perspective of an underclass or minority struggling to gain equality.

According to Dr. Srirak Plipat, the Executive Director of Freemuse2 – the main independent organization defending freedom of expression for artists worldwide – the conditions of censorship differ from one country to the next. Nevertheless, he notes, several underlying trends point to bleak prospects for artistic freedoms in the wake of growing anti-immigrant and nationalist movements worldwide. “The practices of silencing others continues,” Dr. Plipat pointed out to me via email. “With security dominating the world agenda,” he continued, “we have seen an increasing number of artists being prosecuted and imprisoned as a result of anti-terrorist measures” and “together with right-wing movements in Europe, and the status quo of traditional repressive regimes, the world is moving to a new low on freedom of expression.”3

In Russia, the ongoing house-arrest of a leading theater director comes amidst a growing cultural crackdown that mirrors the country’s Soviet past. In the 1930s, during the Stalinist purges that witnessed widespread perceptions of the country’s intellectual and cultural elite, artists had to either conform to the demands of state propaganda promoting Social Realism, work in secret, or leave. The prosecution of Kirill Serebrennikov, the artistic director of the Gogol Center, an avant-garde experimental theater, and three of his associates, mirrors the forms of censorship popularized during the Soviet Union under Stalin. Serebrennikov stands accused of embezzling more than $2 million in government funds,4 a popular tactic the Kremlin uses to sully the reputation of its critics.5 Many in Russia’s cultural sector point to a more sinister plot: that being Serebrennikov’s award-winning plays, which are often critical of Putin. “Now the Kremlin is coming for the young and the talented—to control the theater, to push out independent cinema, to cancel concerts,” Mikhail Zygar, a journalist and the author of a best-selling history of Putin’s presidency, said recently.6

Perversely, censored artworks and individuals can become typologies of cultural martyrdom, at best going viral and coming to the attention of Western artists and activists. In such cases, the social antagonisms of a censored event, art work or individual, are given increased visibility. Paradoxically, and by virtue of the very act of being censored, they are infinitely multiplied by social networks online. Ai Weiwei is an excellent example of this. In 2011, Weiwei was arrested and brutally interrogated by Chinese authorities and given a sentence of four years house arrest. As a result, Weiwei’s career skyrocketed in the West, taken up by institutions eager to reap the cultural capital of platforming a politically engaged and socially relevant artist.

In Turkey, censorship happens on a much clearer level. One notable case is that of Zehra Dogan (On Sunday, February 24, 2019, after two years, nine months, and 22 days in jail, Dogan was finally released from prison), the Kurdish artist and journalist who was imprisoned for over two years on account of painting an image based on a photograph distributed by the Turkish military. The painting was of the predominantly Kurdish city of Nusaybin in ruins with Turkish flags flying above.7 Dogan’s case is one case among many in the Turkish arts sector, where today a sense of hysteria prevails, leading to widespread self-censorship in nearly all facets of culture.

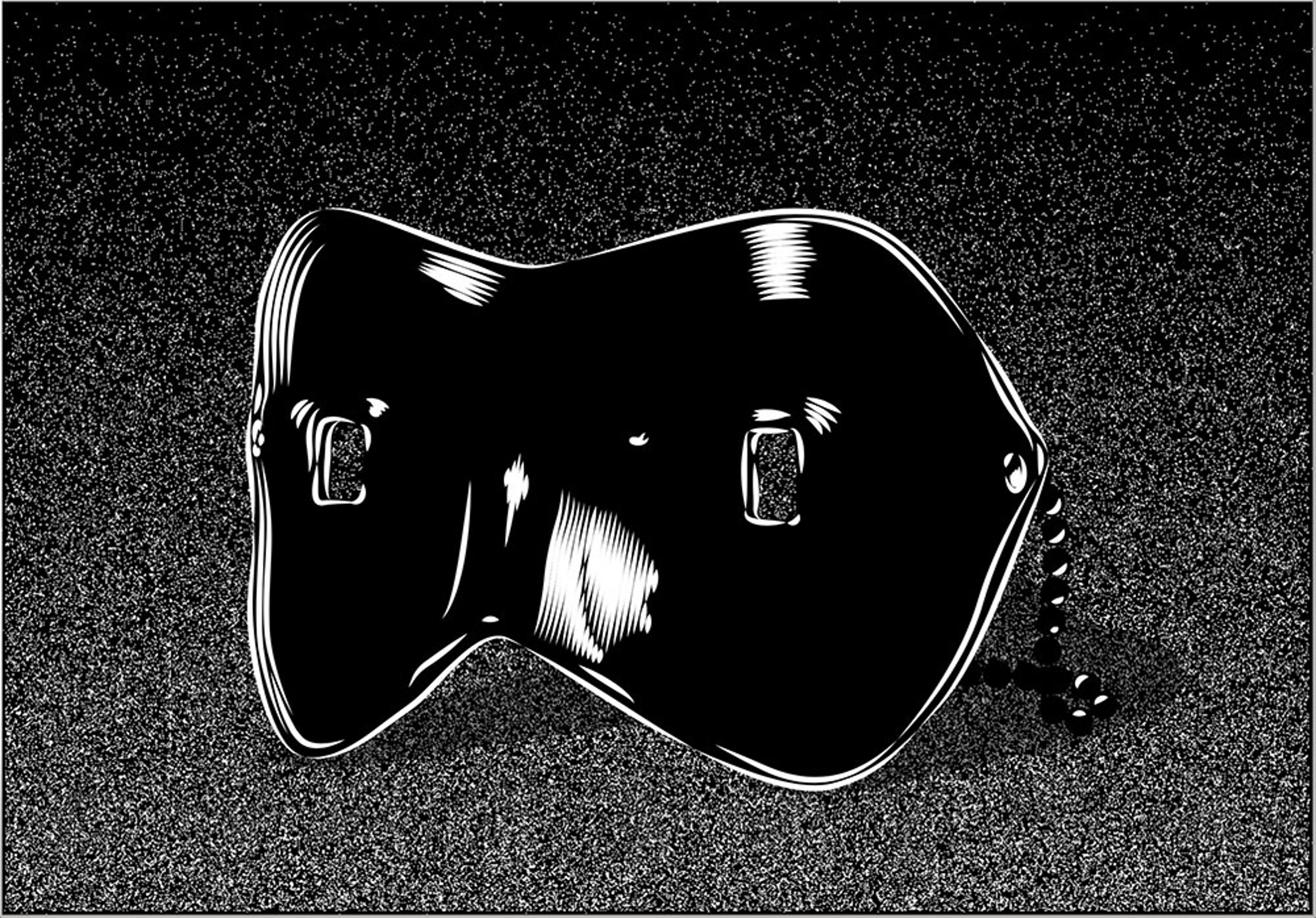

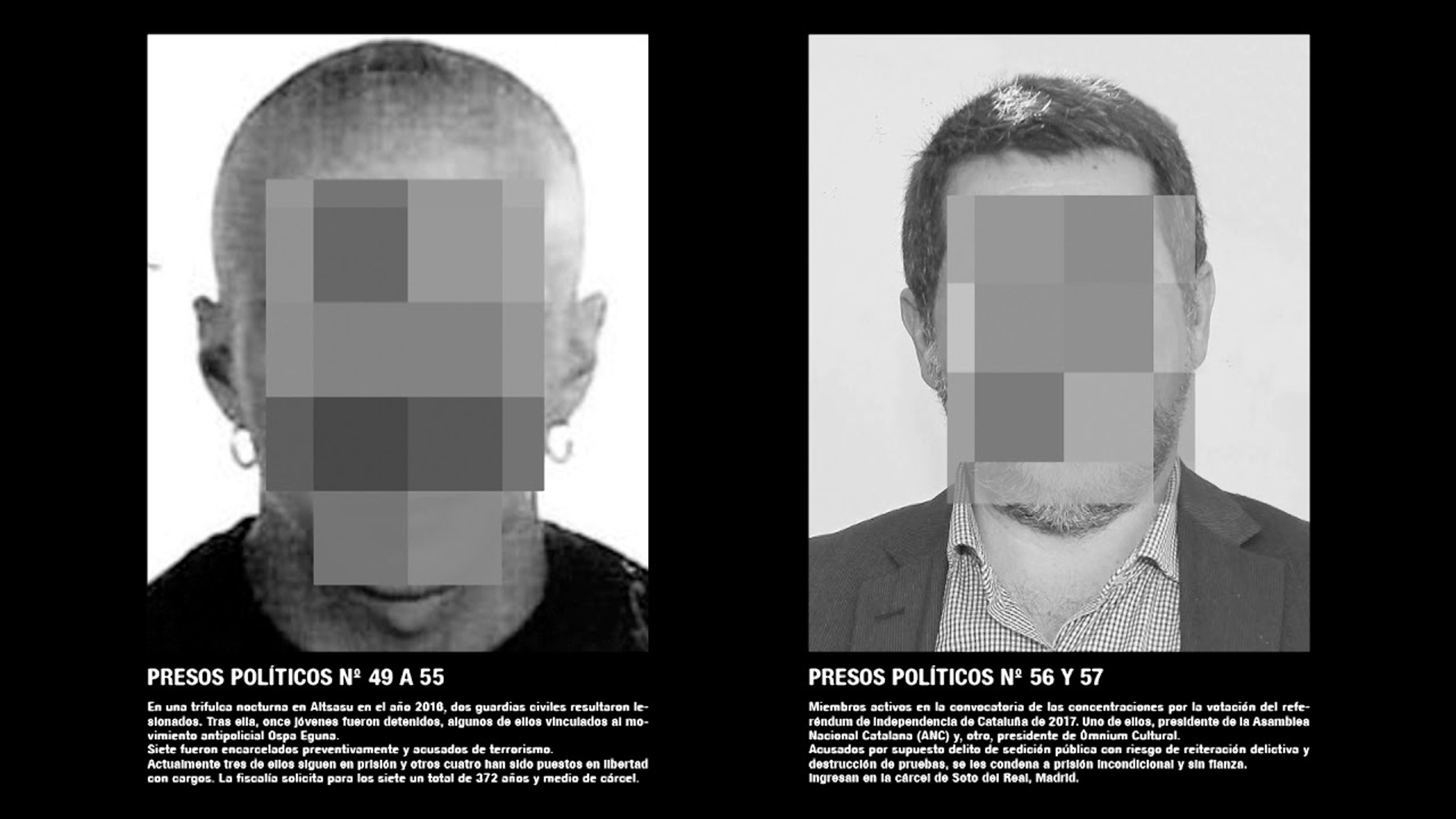

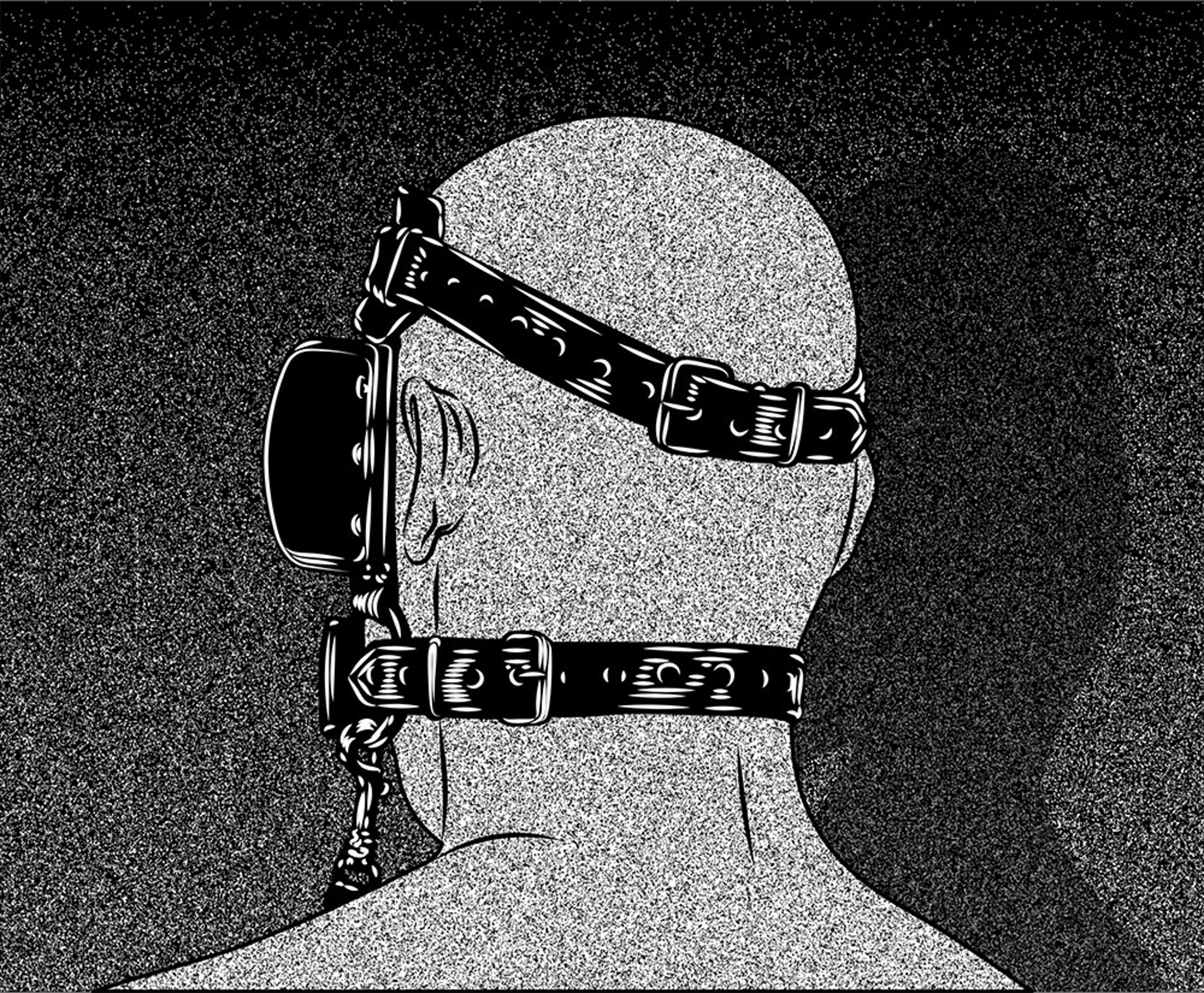

Europe fares only slightly better. In 2017, Spanish authorities in Madrid issued an arrest warrant for Mallorcan rapper Valtonyc. His arrest came following the release of a song critical of the monarchy, which Spain uses to assert control over regions like Catalonia and Basque Country that have been fighting for greater autonomy since before the fall of Franco. Over the last two years, the case for censoring art works and songs that support Catalan independence has reached a near fever pitch. ”Persecution for reasons of conscience is normalized,” said the artist Santiago Sierra, after his work was censored at ARCO Madrid in 2018. The censored work, entitled Political Prisoners in Contemporary Spain, was taken down after authorities found it to be platforming the words and images of Catalan political prisoners. The work consists of a series of 24 pixelated portraits of recognizable figures of the independence movement, Oriol Junqueras, President of a Catalan Nationalist and Democratic Socialist political party; Jordi Sànchez, President of the Catalan National Assembly; and Jordi Cuixart, of Òmniun Cultural, all of whom remain in preventive detention accused of rebellion and sedition as a result of their participation in the Catalan push for independence. Sierra’s work was censored at the art fair in Madrid for platforming these individuals, their faces blurred, but their words visible.

Santiago Sierra Political Prisoners in Contemporary Spain, 2018

According to Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, in the West, “Society develops a type of self-censorship with the knowledge that surveillance exists,” which can lead to “a double language” where no one “says what they really mean,” producing, in the long run, “low-level fear” and “conformity.” The same occurs within arts institutions, where censorship works akin to selective hearing, i.e., the decision to platform one exhibition or artist and not another. “That’s the way that the bulk of censorship occurs,” Assange points out, “decisions [that]” may seem arbitrary in nature, “are made as a result of personal or shared experience. And what happens if you don’t tow the party line? People are compromised,” negatively impacting “their employment [sic] or social opportunities.”8

In December 2018, for example, news broke that Ralf Beil, director of the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany, was without warning let go. Suspicions became rife about possible reasons behind his dismissal. His departure came as a surprise to the public, visitor numbers at the museum were good, public relations with the local and international art press were healthy, and there were no financial scandals to report. The problem? An exhibition in the works planned for 2019 centered on fossil fuels: Oil—Beauty and Horror in the Petrol Age. At issue was that Wolfsburg, where the museum is located, is the global headquarters of carmaker Volkswagen, which maintains an art foundation that is the sole sponsor of the institution.9

What’s clear is that the nature of censorship today has evolved, therefore requiring new strategies of resistance.

During the prohibition of culture in the Soviet Union, Roentgenizdat became a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc. Roentgenizdat, or “ribs” as they were also known, consisted of improvised gramophone recordings made from X-ray films. Mostly made through the 1950s and 1960s, they were a black market method of smuggling and distributing prohibited music by foreign and emigre musicians. Artists such as Pjotr Leschenko or Alexander Vertinsky, or Western artists such as Elvis, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys, Ella Fitzgerald and Chubby Checker were banned from broadcast in the Soviet Union. Ribs became a means of evading censorship in the 50’s and 60’s. Today, new tools are needed to evade censorship in environments that manufacture consent through a more subtle form of propaganda.

Founded in February 2017, the University of Underground10 in Amsterdam is a hybrid design institution that supports unconventional research and practices that “makes innovative use of design, linguistic, experiential, political, musical and film practices as tools to engage members of the public with the experiences and the debates created.” They are actively involved in bringing to light how educative structures can be built to combat “the commodities of knowledge, power and politics.” At the threshold of a nonlinear approach to critical pedagogy, media literacy and production, the University of Underground supports critical practices in art and design through a free education model that challenge existing circuits of self-censorship in the West.11

Another initiative called Artists-at-Risk (AR)12 (founded by Marita Muukkonen and Ivor Stodolosky), envelops the curatorial field as a site of cultural resistance at the intersection of human rights and arts. Building and partnering with a multiplicity of institutions (residencies, artistic initiatives, unions, state and municipal institutions) across Europe and beyond, Artists-at-Risk offers AR-Safe haven Residencies for artists who face acute prosecution and censorship, which they say has only become more difficult over time. “As the EU pulls up the draw-bridges of ‘Fortress Europe’ Artists-at-Risk has begun building AR-Residencies outside of the Schengen area, with residents currently in or passing through relatively safe countries such as Cote D’Ivoire and Tunisia. The rise of fascism in Europe is also increasing the applications from within the European continent, which is forcing us to revise our selection process.”

Since its founding, Artists-at-Risk has hosted approximately 30 art-practitioners (AR does not provide exact figures, as some residents “fly under the radar”). Ramy Essam, known to the world as the voice of the Egyptian revolution and “singer of Tahrir Square,” who was imprisoned and tortured repeatedly leading protests against Mubarak’s regime, SKAF, Morsi and lastly Sissi, was hosted by AR in Finland in 2016. AR hosts curated events, conferences and a dedicated “AR Pavilion” within and parallel to large art events. Recently these have been shown at Athens Biennale, Istanbul Biennial, Matadero-Madrid, Nordic Embassies, and Aufbauhaus in Berlin — where they platform artistic practices of AR Residents.

Strategies such as those employed by Artists-at-Risk and the University of Underground are exemplary of new strategies artists and curators are using to evade censorship and self-censorship today. Whether they are using geopolitical safe-havens and international protections, or developing tools to analyse how censorship is evolving today and the ways that information is weaponized by regional governments, new initiatives are clearly necessary in the Western states which openly accept the value of free speech and democracy. In democratic and demagogic societies alike, such methods can be used by cultural practitioners as means of re-locating channels of resistance.

2 “We believe that at the heart of violations of artistic freedom is the effort to silence opposing or less preferred views and values by those in power – politically, religiously or societally – mostly due to fear of their transformative effect. With this assumption, we can address root causes rather than just symptoms – if we hold violators accountable.” (www.freemuse.org) Accessed 4 February 2019.

3 Email correspondence in December 2018

4 “Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov goes on trial for fraud”, BBC, 7 November 2018. (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-46125108) Accessed 4 February 2019.

5 Tom Parfitt, “Russia Opposition Leader Accused of £1.1m embezzlement” The Telegraph, 14 December 2012. The charge of embezzlement is a popular tactic used to silence critics in Russia. Since 2012, Alexei Navalny, the leader of a major opposition party in Russia, has faced accusations by the Kremlin of embezzling $1.4 million USD, charges which often come on the eve of national elections. (https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/9745288/Russia-opposition-leader-accused-of-1.1m-embezzlement.html) Accessed 4 February, 2019.

6 Anna Nemstov, “A Theatrical Moscow Trial Draws the Ire of Russia’s Cultural Elite”, The National, 14 January, 2019: (https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/01/russian-artist-serebrennikov-culture-trial-moscow/580306/) Accessed 4 February 2019.

7 Jasmine Weber, “Imprisoned Kurdish Artist Pens Thank You Letter to Banksy”, Hyperallergic, 18 July 2018. (https://hyperallergic.com/452059/zehra-dogan-letter-to-bansky/) Accessed 4 February 2019.

8 Seung-yoon Lee, Julian Assange: ‘Western Civilization Has Produced a God, the God of Mass Surveillance’ Huffington Post Blog, 2017: (https://www.huffingtonpost.com/seungyoon-lee/julian-assange\_1\_b\_7560710.html)

9 Kate Brown, A Museum Director Planned a Show About Art and Oil. Just One Problem: His Institution Is Funded by Volkswagen, Artnet news, 2018: (https://news.artnet.com/art-world/we-are-living-in-a-world-with-ever-diminishing-ethic-values-ousted-museum-director-ralf-beil-on-the-urgency-of-artistic-freedom-in-the-face-of-big-sponsorship-1424839)

10 University of the Underground, “About”, (http://universityoftheunderground.org/about) Accessed 11 February, 2019.

11 In support of the University of Underground, a roentgenizdat vinyl record is being produced with contributions from Noam Chomsky, Jonsi of Sigur Ros, Peaches, Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth. The limited edition vinyls will be used to support the scholarships and endowment of the University of Underground, which relies on a tuition-free model to operate.

12 Artists at Risk, “About”. (https://artistsatrisk.org/about/?lang=en) Accessed 11 February, 2019.

Note: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of Collecteurs