Welcome to Episode Two of the podcast series SUBSTANCE by Collecteurs. Here, we take a deeper dive into the figures included in our SUBSTANCE 100 List, which features a diverse group of artists, activists, and collectives making substantial change in the world today.

Our guest is Edgar Heap of Birds, an Oklahoma-based artist and academic from the Cheyenne and Arapaho nations. For more than 40 years, the multidisciplinary artist has been advocating for indigenous communities and social justice through his works, which have been exhibited and featured in collections worldwide.

In this episode, we speak to Edgar about his unique blend of activism and art, starting with his 1990 project Building Minnesota, which honored the 40 Dakota men killed in the largest mass execution in American history. He also discusses his most recent project, Surviving Active Shooter Custer, shown at MoMA PS1 in 2019. Last but not least, Edgar shares his thoughts on the landmark decision by the Supreme Court, made at the time of this recording in early July, declaring half of Oklahoma Native American land.

Listen to the podcast episode here:

For this podcast episode, Edgar Heap of Birds has made available some of his unique ink on rag paper works exclusively on Collecteurs.

Purchase Unique Works by Edgar Heap of Birds

Evrim Oralkan (EO): Edgar, first of all, thank you for joining us. It’s really an honor to have you. I have a lot of respect for your practice and long history of works. I just want to ask you, first, can you share your thoughts about the current situation of protests and the brutal racial oppression we are witnessing as a society today?

Edgar Heap of Birds (EHB): Well, it’s… We kind of go back to, in a sense of, you know, my piece I just created a few years ago, called Surviving Active Shooter Custer. And, so, there’s been so much racial violence highlighted in the contemporary society in America. But, of course, if you go back to Native American life and history, you know, ours began 500 years ago, the terrorism and violence.

And, so, we want to remember how this country was founded on violence. The armies, the colonies, the British government, you know, all the European governments that came here to actually brutalize the Native citizens and kind of rape this whole natural world of the Americas.

And it continues, the issue with the pipeline and Dakota was similar. So, all these things are very violent and very invasive and continue. But, of course, the visuals, the video and the documentation of this blatant violence in Minneapolis and elsewhere, it makes it more of a pivotal moment. But, of course, for Native people, we suffer and we’re challenged every day.

EO: There has recently been a wider discussion on the civic monuments that are standing symbols of a colonialist and racist past. Since Donald Trump’s speech at Mount Rushmore on July 3rd, debates on whether the monuments should be destroyed have increasingly come to light. You’ve addressed civic monuments in your work before, in Native Host, which began in 1988 and addressed the formation of cities and monuments over Native lands. Could you tell us how you started with this project and what you hope to see in terms of the destruction and replacement of these statues?

EHB: What I did with that project, it began in ’88 in New York City, at City Hall Park. And I was with a group of artists that were given a commission. It’s a very, very tiny amount of money, but, to do an intervention or present their work. And, so, I really take it very personal and in a very honorable way to come to different locations in America and elsewhere in the world as a welcomed visitor, a welcomed traveler, in a sense, hosted by whoever the Indigenous population is in that location.

So I already challenged the first precept of Native America, which is that it doesn’t exist, you know, there’s over a thousand nations in this continent, maybe more than a thousand. And, so, they’re all different nations, different local governments, different local ceremonial people.

image left: Edgar Heap of Birds – Native Hosts, 1998 – ongoing. Courtesy the artist.

And, so, when I come to New York, I’m not coming to be a Native American. I’m coming as a Cheyenne man. I’m a leader of the Elk Warrior Society. I do have a certain distinction within my tribe and the ceremonial distinction in my religious practice. But I come forward as that kind of person from the Cheyenne Nation. But I’m going to have to certainly be honorable toward the nations of New York, or what we call New York. Many of us, Shinnecock Nation on Long Island and so forth, Mohawk, Tuscarora, Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga. And so that was my premise was to come to New York and honor the tribes that are already there and say, I’m really very fortunate to be welcomed by those tribes on that island.

Edgar Heap of Birds – Native Hosts, 1988 – ongoing.

And, in doing so, I wanted to have the rest of New York pay homage to the hosts that they’re being welcomed by or they sort of put up with them, I guess, more or less, to be there as well, though, the white people. And they don’t really think of that. And Mayor Koch was the mayor at the time. And so everyone thinks Mayor Koch is the host of New York. Well, no, no. It’s the tribes that are from that area of the world, they should be the host, seen as the host. And, so, I think when you take that kind of premise, you’re going to be more respectful and more honorable. And history will be represented in a much more fitting way.

But you have all these statues all over New York City that are mainly white people, white men. You have the Dutch who are said to have founded New York, you know, it’s really ridiculous as well. And it has been there for 20,000 years or longer, you know, as far as a civic community of Native people. So, to challenge that Eurocentric history of self-identifying as the leadership and the owners.

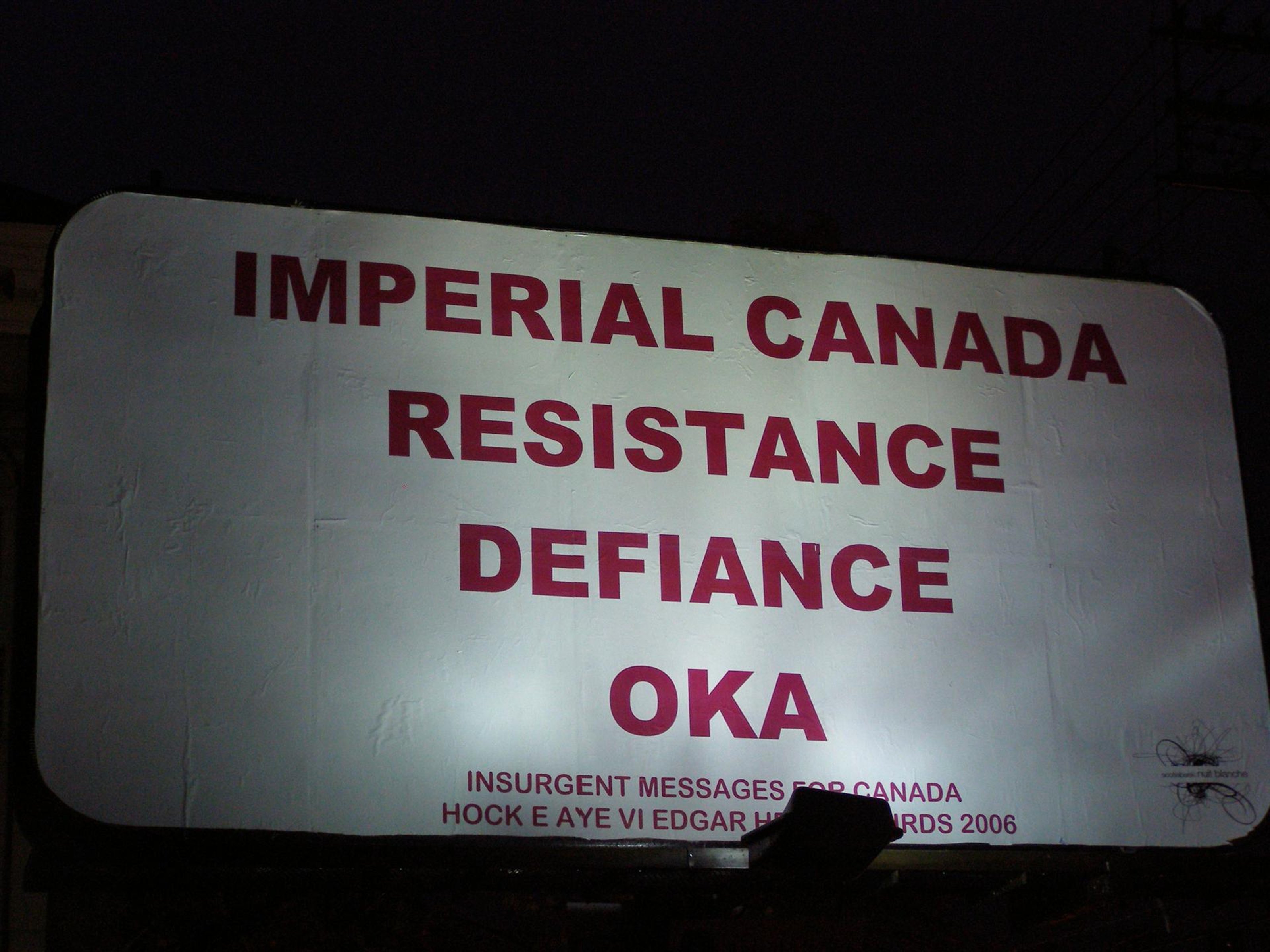

My Native Hosts signs are very humble ways of honoring the tribal people. So, I’ve executed those sign panels in Vancouver, you know, Chicago, LA, all over Arkansas, all over the country. It’s been going on since ’88.

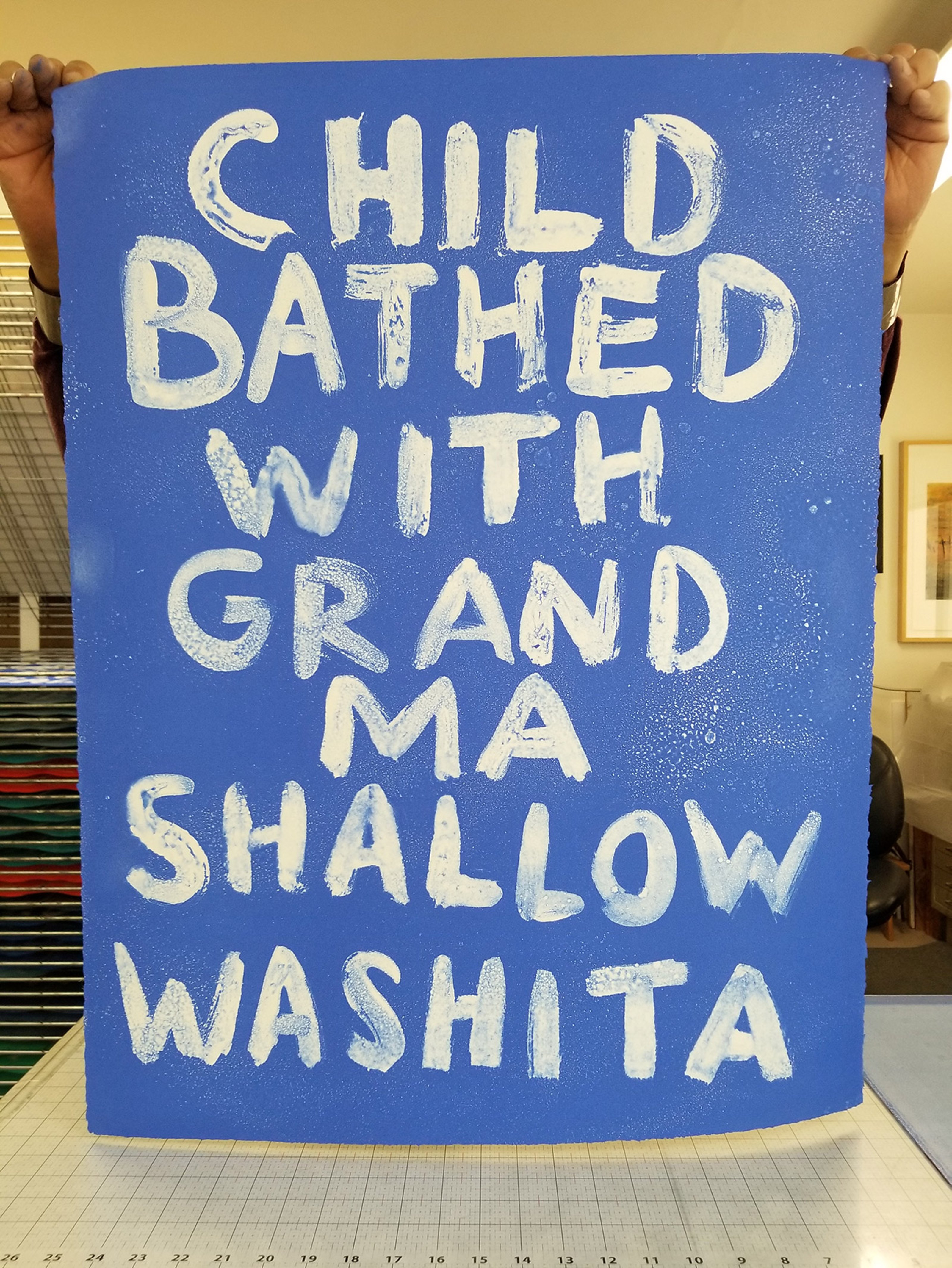

EO: I know that you’re Cheyenne and I was looking at the print that you recently sent to me: Child Bathed with Grandma Shallow Washita. And when I was looking at the battle of Washita River, as the white perspective says—or the Washita Massacre, as you probably would call it—I noticed that, you know, your exhibition at MoMA was titled after Colonel Custer, as well. So, there are several statues of General Custer, as well, and this battle happened in your hometown, in Cheyenne. What are your thoughts about Colonel Custer’s legacy?

EHB: Well, we have to really challenge it. We have to take down the honorable monuments to Custer. We have to understand how vicious and how it was terrorism. You know, they killed children, they kind of coaxed the tribe to be in a stationary position, by treaty, so that it can be attacked. You know, they attacked them in the winter, when they couldn’t be very mobile, and they actually built a fort, called Fort Supply, to restock Custer so he could kill the Cheyenne. You know, so, very, very horrible, typical, violent episode in American history. They also took the tribe away later, the men, and put them in prison in Florida and Fort Marion, Florida. My grandfather was one of the prisoners of war. And I linked that up with what’s happening in Guantanamo Bay today, with the so-called Middle Eastern enemy combatant.

So, America keeps reflecting this kind of violent behavior to the world. So, we have to really challenge that in Oklahoma and elsewhere, with Custer. There’s a county in Oklahoma called Custer County, which is near the massacre site. And when you go, if you got in trouble in Custer County, you had a problem with the law, you have to go to court. And if you go to court, it’s a white court. And you walk in the building, and there’s a big portrait of Custer in the building. And you’re a Native Cheyenne person who was massacred by Custer, and then you go to court and Custer is in the court, you know? So all these things…. I’m not going to show you any kind of, like, fairness. So, so, yes, to challenge all these symbols is very important.

Edgar Heap of Birds – Child Bathed With Grandma Shallow Washita. Courtesy the artist.

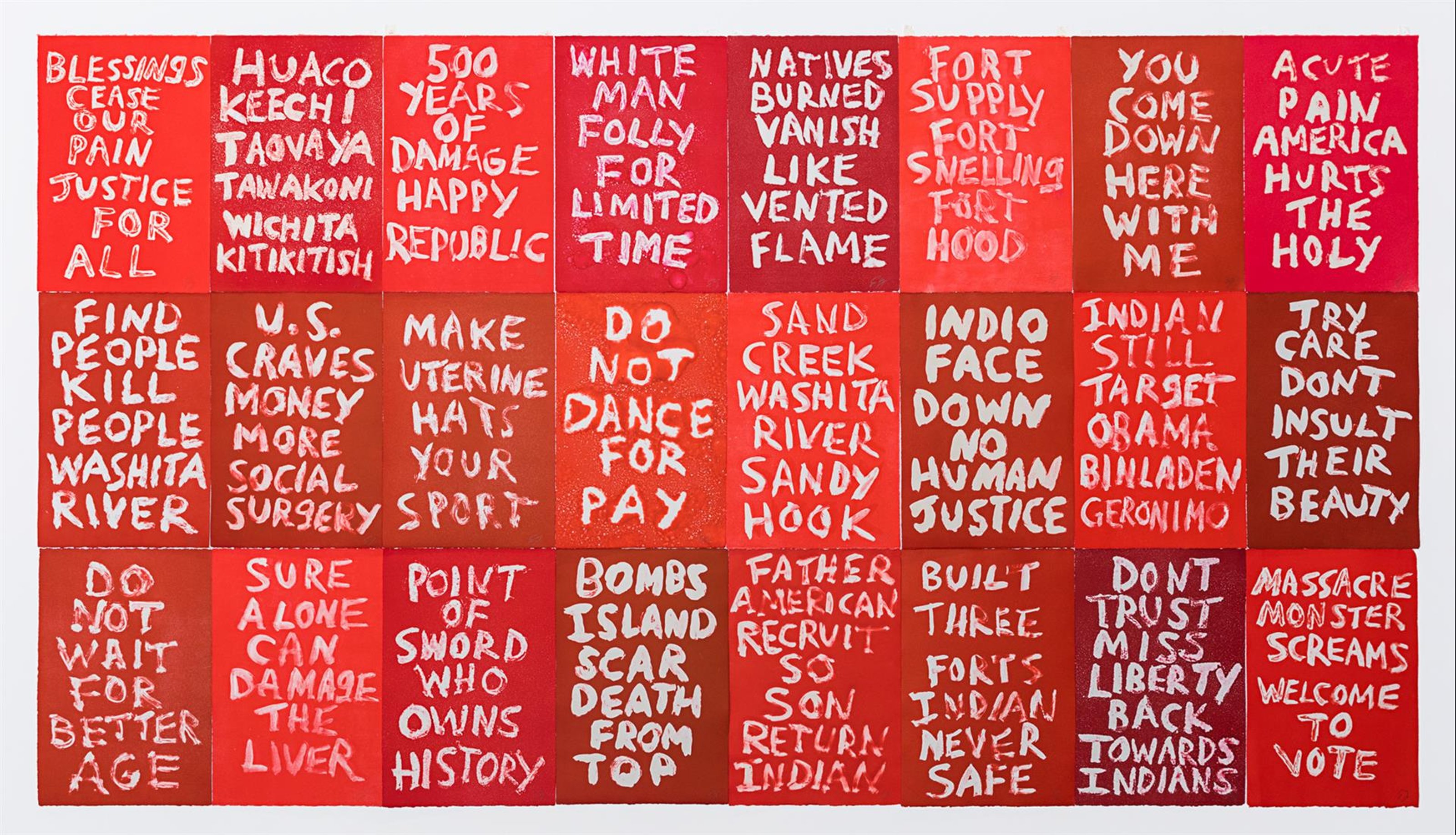

Edgar Heap of Birds – Genocide and Democracy. Courtesy the artist.

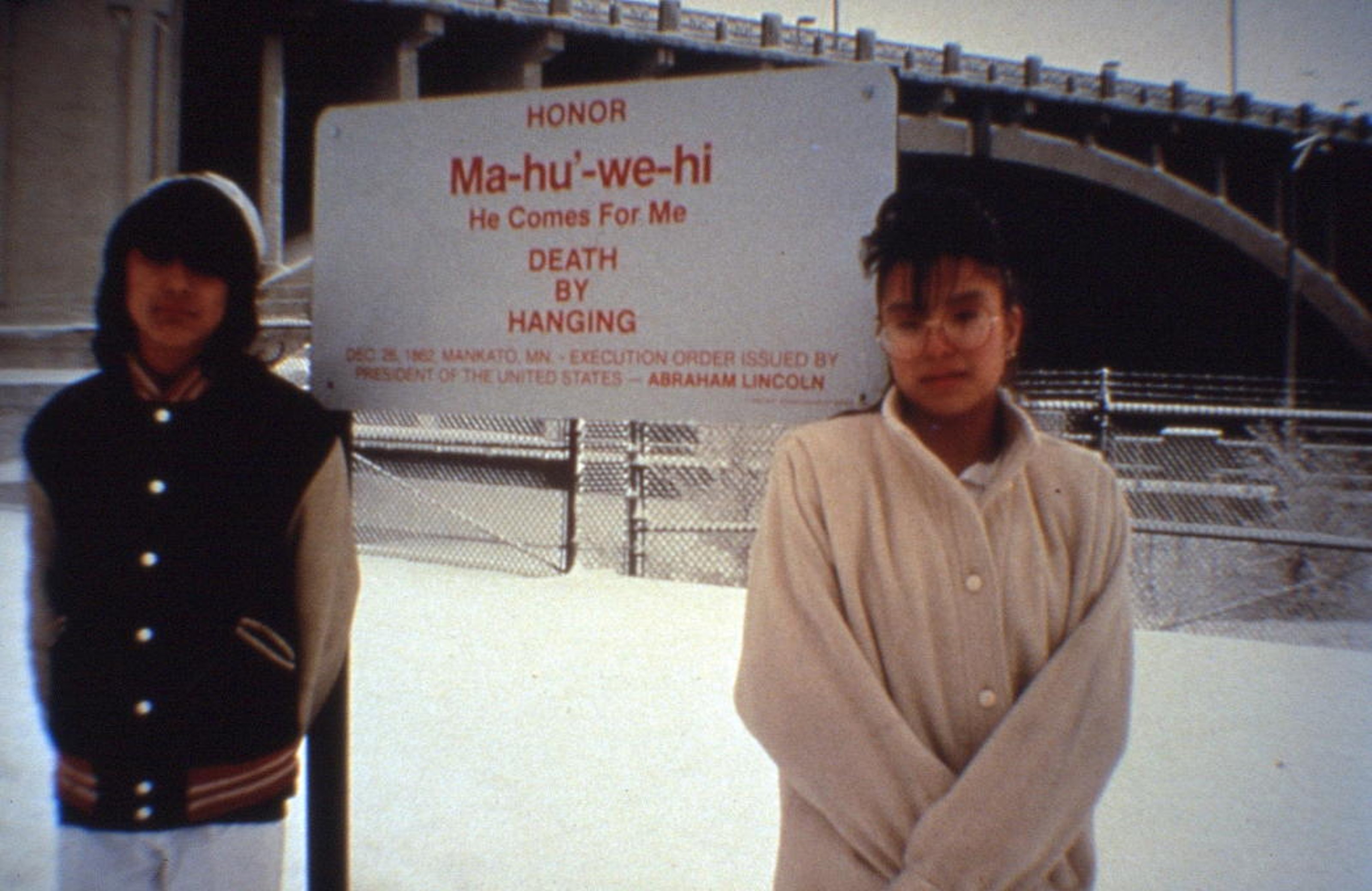

EO: Absolutely. Thanks for pointing that out. One of the strategies that the Black Lives Matter movement employs in holding the state accountable is to keep the memory of the victims alive by saying their names. You know, we’ve all heard, “Say their names: Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Elijah McClain.” In a way, you are the original “say their names.” When I look at your Building Minnesota in 1990, which was commissioned by Walker Art Center, you created 40 metal signs, which imitate the look and lettering of public street signs. On a white background with red letters, it bore the names—in English and Dakota—of the 40 Dakota men, prisoners of war, who were hung by executive order for the role they played in the Dakota-U.S. conflicts of 1862 and ’65. So, these 38 plus two people are considered the largest mass execution in American history. By using the signs to engage people in Minneapolis, you drew this attention to a history that is nowhere near resolved. I want to tie this into today. I feel like this work is a masterpiece and, you know, going back to it, being in Minneapolis, you know, what are your thoughts about today, what’s happening in Minneapolis? And the past that you… you created this in 1990.

EHB: Minneapolis is a very, kind of, provocative location. As you said, it’s the site of the largest mass execution in America’s history, which was perpetrated by President Abraham Lincoln. And, so, there’s been a lot of amnesia and denial. My work was very feared when I created that work with the Walker—and they have since never bought that work, it needs to be clarified. They paid a small fee to have me create it as part of my solo exhibition, but they never really acquired it. And they never wanted to put it back out permanently, even in their sculpture garden. So, hoping to shed any kind of relationship to it.

EO: In the work you clearly identified the perpetrators of these violent acts. You know, the signs bear the name of Abraham Lincoln, who signed the executive order for the 38 by Andrew Johnson. The piece quickly became controversial because a lot of people started objecting to this portrayal of Lincoln, a great hero in their opinion. In your opinion, what is the importance of remembering the names of the victims of state violence? Can this be a way of reckoning with history to remedy the present?

EHB: Well, certainly. And the reason I created that piece, of course, again, I was coming from Oklahoma, coming to the Walker, having been celebrated, having a solo show in the museum. But I wanted to not just have all the attention paid to me. When I found out about the massacre, I was appalled and I had to comment about it.

And, particularly, I asked to work with middle school students who were from the Dakota tribe. And I had maybe 30 children that I worked with, and some of them were descendants of those men that were executed. So, you know, you have to be honorable and have to think, well, what should I tell these kids? These kids are living with his legacy, this dysfunctional, violent American legacy, and they’re still suffering.

Edgar Heap of Birds – Building Minnesota, 1990. Courtesy the artist.

We went to the graves of the men that were hung. We met with the tribal chiefs. You know, some of the students came and helped me put the signs in the ground. We had prayers offered, you know, so it’s not only like a newspaper story or a media event. These issues and events are really about people and their lives and their legacies.

I felt really good to share this with the children in the community, in Minneapolis. But, of course, Minneapolis was very fearful and it became controversial, but it’s just the truth. And so be it.

You know, we had a problem. I’m not sure if you’re aware of Sam Durant. You know Sam Durant?

EO: Yeah.

EHB: To bring up a good example of how to work with communities, which my project I think was, and to bring it forward with the named project and what’s going on in Minneapolis. And, as I said, the Walker kind of shunned the project and disowned it, in a way.

But still the tribes and the people there in the community remember my efforts. And of course they remember the legacy of those 40 that died. And I have all the work here at my studio, they shipped it back to me. So when Sam messed up that stuff, I went up there to help him a bit with another project. And then they came to my hotel. And the Indians wouldn’t go to the Walker, they said, “That’s an evil place. You got to put tobacco down, you got to pray to go inside.” So, they said, “Don’t go in there anymore.” I said, “Okay, I’m not going to go in there.” I said, “You got to come to my hotel to meet me.” And they came and they said, “Well, we want to buy your piece, but we want to pay you in 1990 prices.” Again, like the Public Art Fund, they wanted to cheat you.

I was like, oh man. I said, “You can’t go back to that time.”

image left: Edgar Heap of Birds – Building Minnesota, 1990. Courtesy the artist.

EO: Absolutely. I also know in Native Hosts in 1988, we spoke briefly about the installation at City Hall Park, which was a series of signs dedicated to the tribes that once lived in New York, and the Public Art Fund was behind the initiative. At that point, Mayor Koch censored the installation. I believe there could only be six signs, even though there were 12 tribes. You know, and you said afterwards, “I feel very strongly that whenever you step out of the door with art, it’s a dialogue.” Well, I think I have to add that there was graffiti that was painted over the signs, right? And that you felt very strongly that when you step out of the door with art, it’s a dialogue; you have to allow people to respond to your work. If they graffiti it, well, it’s a part of their response. But the Public Art Fund back then said, “If we let them graffiti on your works, then we’ll have to let them do it on everybody’s work, so we have to clean it.” Apparently, you responded as “Okay, clean them.” Then when you went to get your final payment, they billed you for the cleaning, which I found super absurd. And I want to hear your thoughts on this.

EHB: Well, yeah, I was a young artist, you know, and it was a big time thing in New York City. And it wasn’t great working with the Public Art Fund, but I felt good getting, again, representing the tribes on land, challenging Mayor Koch, in a sense, but then when they wanted to clean it and they deducted my fee.

EO: How much was the fee, out of curiosity?

EHB: My fee was like, I don’t know, like, $1,000. It was like nothing, really. And then they took like $150 out for the cleaning fee, and it was just so terrible. And they left me a check, and they wouldn’t even come and do… they left the doorman [to] do it for me. You know, it was like they were really ashamed. But here we are talking about it again. But it’s the insult and not the respect you want to pay to the tribes. I mean, you took away their land, you murdered their people, all these things, and still you want to insult the memory by doing that kind of action. It’s terrible.

Edgar Heap of Birds – Insurgent Messages for Canada, 2006

EO: Your work is especially interested in health and healing for Native communities. In your project, Health of the People is the Highest Law, you created prints that outline the health problems Native communities face. Specifically, diabetes and lack of resources that prevent communities from accessing healthcare. We know that the coronavirus crisis has hit minorities especially hard in the U.S., the Navajo nation being one of the communities that suffered major losses. Are there any initiatives or movements to go back to traditional ways of eating and healing? And how has your experience been since the crisis started?

EHB: Well, it’s been very detrimental on the Navajo reservation, and that’s mainly from people coming from the outside, coming into the nation. They’re very removed from society as far as urban situations, they’re very isolated. And so the Cheyenne and Arapaho have a similar situation where we’re isolated and we’re far healthier to be isolated. If we have people coming in from the outside, then we’re going to have more stress to be ill. No, but we have a very good effective eldercare program on my reservation. And they’re active with… We have a buffalo herd, for one example, we have a large buffalo herd. And the buffalo are very low-cholesterol, high-protein, you know, low-fat. So the elders all get free buffalo given to them. And so there’s always initiatives to kind of get people back into a healthier diet, which was perpetrated on them from the army. The army came here and restricted the tribes to live on reservations. Wouldn’t let them hunt their natural game and gave them preservative food, high-sugar, high-salt food. And all that kept into the diet and it became this pseudo…what they call a traditional food, which was preservative foods. So, we have to go back and restart beyond the interaction of contact with Europeans. But we’re more involved with health and those issues now. And I’m very, very optimistic that things will change.

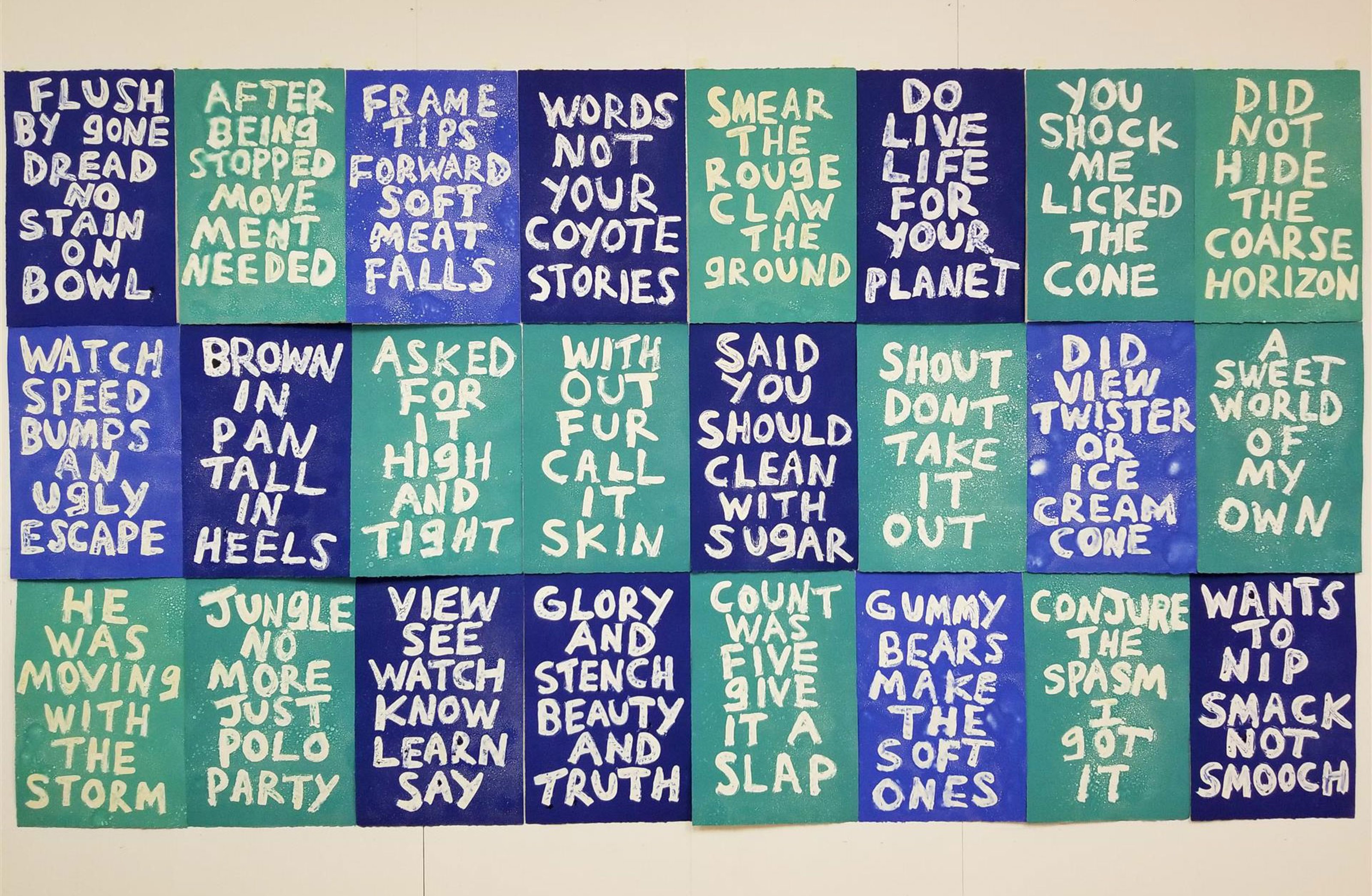

Edgar Heap of Birds – Not Your Coyote Stories. Courtesy the artist.

EO: That’s good to know. Your most recent project, Places of Healing, shows Native ceremonial sites across North America and Hawaii for communal healing and prayer. With the current state, how do you look for healing in your life? What are things that bring you hope during a time of crisis?

EHB: Well, I’m really, really excited right now… Because corona has been a problem in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma as a state. And, so, we’ve had to delay our ceremonial earth renewal because [of] the way things are going in Oklahoma. And so we’re going to move it. We moved it off the solstice and we’re moving it into, you know, in about two weeks, about three weeks from today. So, from that point, we will be doing our ceremony. And I do work with a young man to renew the earth through his sacrifices in the ceremony. I’m his instructor. I’ve been involved; I’ve been dancing for 16 years myself, and then about 30 years total. So I’m really happy that we’re going to be able to go and create the lodge and make all the offerings and prayers, and do our traditional religious practice we’ve had for hundreds of years. So, we’re very, very healthy in a ceremonial way to go forward and make this renewal.

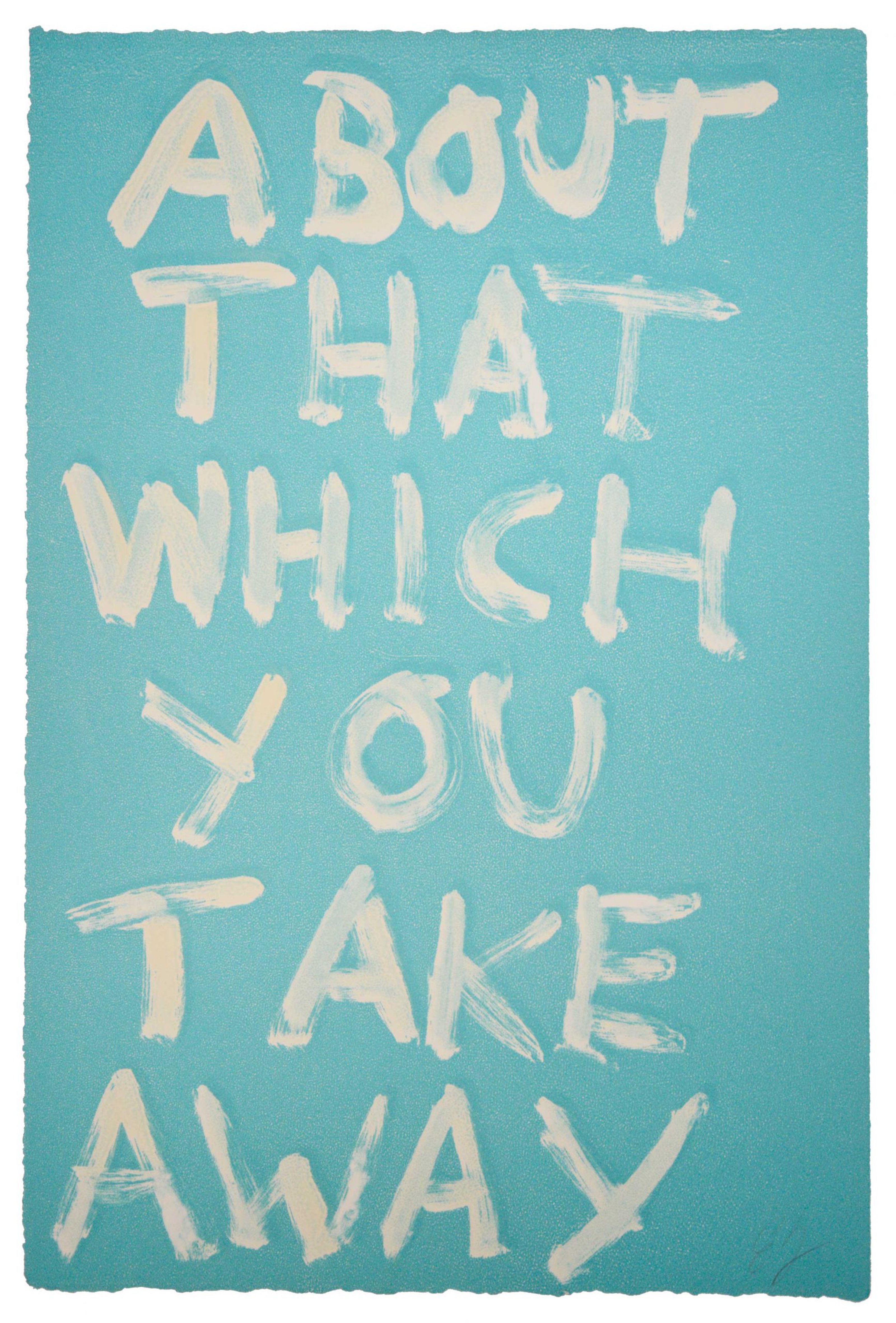

Edgar Heap of Birds – About That Which You Take Away, 2000-2010

EO: You create ghost prints with a special technique; I’m really fascinated by how you describe the concept of a ghost. When you’re making, there’s still a residual amount of ink on the plate when you do the first fold, so you can make a second, fainter print. You use this as a metaphor for the marginalized life of Native people in the U.S. You previously said, “We’re so faint. We hardly exist in contemporary society. And history is so biased.” On that note, the Standing Rock protest was able to unify the many Native tribes that were so separated before. How do you think the spirit of unification that was formed during Standing Rock will take shape in the future? What are some possibilities going forward?

EHB: Well, I think that was really one of the most important events since Wounded Knee, really, was to have Standing Rock, and I made a series of prints about that, and the tribes coming together and gaining energy from each other. And actually contributing to the effort to sort of sustain that attack, sort of this rebuttal against the pipeline construction.

You know, so, all that kind of brought together unity within the nation of the U.S.A. of Native people. And we need to have that continue on… You know, there are some public groups like the Congress of American Indians, that’s a political arm that goes forward. And, actually, there’s a letter going out just yesterday to challenge the Washington football team, by many artists of different nations. And that’s part of that kind of unity that we can actually challenge that football team being renamed. So those efforts going forward have spawned out of that Standing Rock experience.

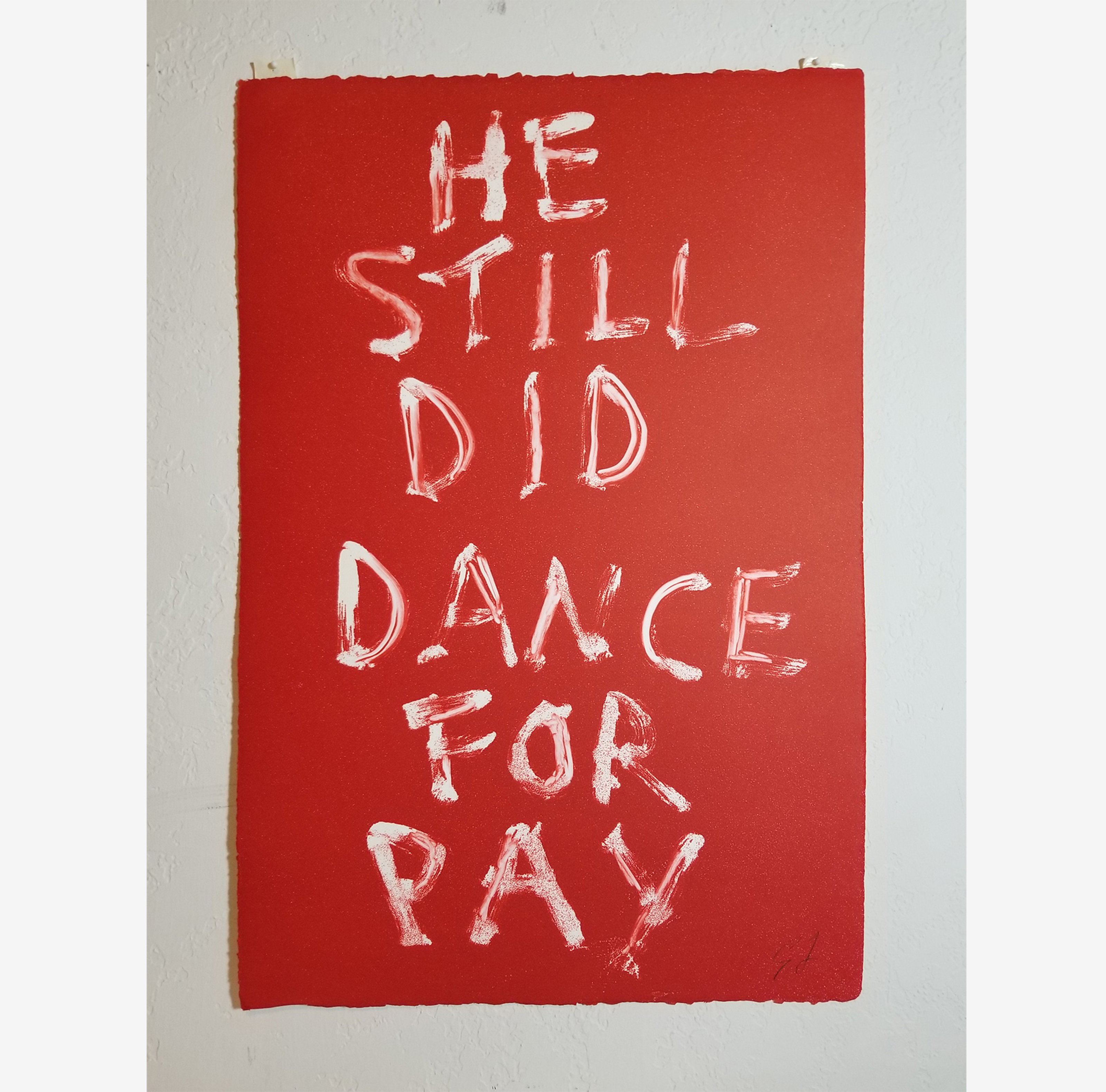

image left: Edgar Heap of Birds – He Still Did Dance For Pay, 2000-2010

EO: I want to point out something that happened a few hours back, before we started the conversation, about the Supreme Court’s ruling that eastern half of Oklahoma, your home state, is Native American land. The decision was five to four. Almost half of the state of Oklahoma is Native land for certain purposes. What do you think about this? What are some of the things that might come out of it for your tribes and for the others that are on the eastern side of Oklahoma?

EHB: Well, it’s a landmark decision that’s very positive. It’s historical, but it’s just… The reality is what the treaty stated. And there were almost 40 tribes brought here from across America, from as far as Oregon, New York, Florida. They lost their territories in those locations and were promised a homeland in a place called Indian Territory. And then that was around the time of Custer being here, as well. So, very turbulent time. And they were promised this autonomy and sovereignty. Then, of course, Oklahoma wanted to become a state within the union, and they took the land away. Primarily most of the land. And then they left a little bit for the tribe to have, and they took it and gave it to the white settlers and made the state of Oklahoma out of it.

So, that was really a breach of protocol and treaty rights. And, so, to have this Supreme Court decision, it is a wonderful, kind of, correction of what has already been defined as Indian Territory and treaty rights. So, with that, you get autonomy from paying taxes. You have business leverage going on, you know, as far as gaining income and so on. Gaming, you know, all kinds of things that are just very good for the tribe.

Even to this day, the Chickasaw tribe is probably the strongest economic apparatus in the state of Oklahoma, from their gaming. And they bought properties in Oklahoma City. They run racetracks, you know, they run baseball stadiums. So, it’s not like something that is going to take away from the state of Oklahoma. It’s actually for an apparatus that’s very healthy and very profitable and it goes back into the state. So, the state can’t really lose… Just that the money shifts to Indian pockets. So, it’s important to have some kind of strength from your own tribe.

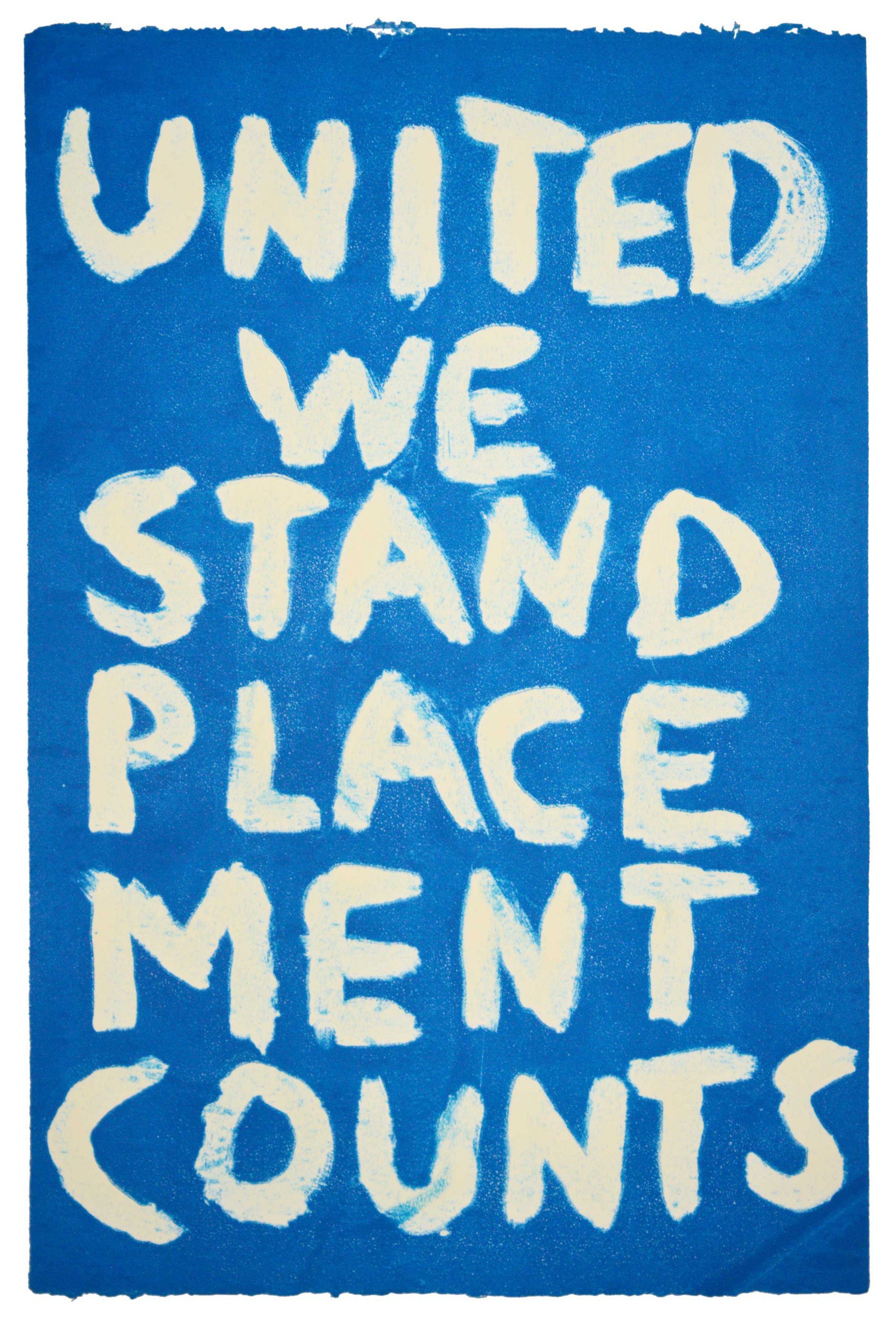

Edgar Heap of Birds – United We Stand Place Ment Counts, 2000-2010

EO: Yeah, amazing. That’s true. I found one of your… You know, we’re what we call the collective museum of private collections. It’s something that hasn’t been done before. But I found one of your statements from the past that says, “The individual does not matter. The collective matters. The tribes have always been about the collective, the seasons, the water, and the plants.” Looking at the current climate with Black uprising, People of Color, Native Americans after George Floyd’s murder, what is… out there? What can happen to unite us—the minorities and the Natives and the Black people—to use this once-in-a-lifetime chance to change, bring really important change. Is it possible?

EHB: Yes, it is. It’s really a matter of empathy, collective empathy, and the care, as you said earlier, about not the individual—which is an American kind of trait in the Constitution; it’s all about the individual. But in the tribal sensibility, you know, you have the elders, you have the youth, and then you have the people of middle age in the center. And everyone should care for the elders. Everyone should care for the youth. You know, everyone should care for the schoolchildren. You know, schools should be the most important thing we have. So, looking forward to caring for others than yourself, you know, don’t put yourself first, put the collective for it, put your family first, your community first. And then you come last. You know, your desires and your needs are last as [an] individual. It’s the collective first. And if you have that sensibility, then you’re going to have a lot healthier kind of life and be more generous.

You know, as I mentioned in another statement I offered a few weeks back, you know, that the tribal identity of Cheyenne people is based upon the chief leadership because they give everything away. And when there’s a communal meal, the chiefs eat last. And so the most generous people, the most honorable people become leaders because they can give everything away and not put themselves first. And that’s how they become leaders. And, so, if you could take that same kind of protocol and use it, say, the most generous people will lead us, the people that are the most selfless will lead us. You know, the people that are most generous and healthy with the environment will lead us. That’s how we will make progress.

EO: What is the next exhibition for you? What is in the works?

EHB: Let’s see, there’s a project in Houston at the Rice University, and that’s going to be in September. I’m doing a piece there called Genocide and Democracy. It’s a series of monoprints. But making this work in Santa Fe was my big push to get the new work on, about water, created. So right now I have a big collage in my studio, and I’m putting together the formation of how to hang it and photograph it, all that. So, this is good.

EO: That’s amazingly well put, Edgar. I think this is all I have. I want to thank you again for joining us, for giving us your opinion on the current landscape.

EHB: Very good. Very good to be with you, and you have very good questions, and I’m hoping for very positive change. Thanks.

EO: Thank you so much.

End.