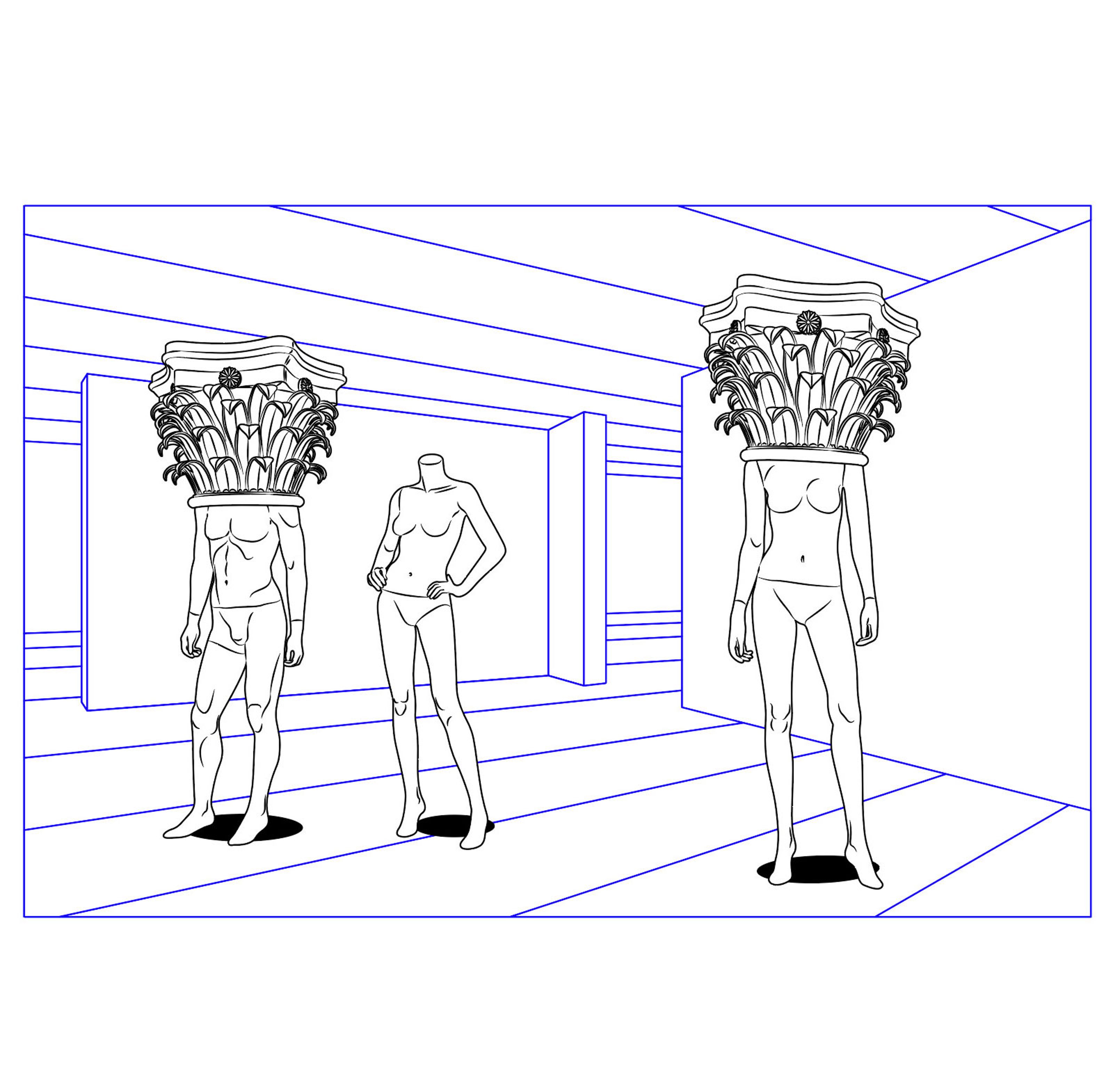

This text is a proposal for a thought-experiment. Its intention is to question the traditions of exhibition-making which today seem natural and eternal. The white-cube format developed in the 20th century is still considered the equivalent of a “neutral” space, even after scores of texts and criticism about the falseness of this neutrality. Art likes to posit itself as an area of radical change, a place where tradition can be challenged and advanced – but what of the conventions present within its own structure? There is a regular format, a temporal interval, that dominates exhibition-making. In commercial galleries, exhibitions last one month; in museums, from 3 to 4. The new biennial-format takes things slower with a more ambitious output, and are punctured by the temporal ephemerality of performance on the opening night.

In other areas of culture, there are clear reasons behind standard temporalities, for instance, the reason that most songs and hit singles are between 3 and 5 minutes long is due to restrictions on the recorded length of an outdated technology. In the 1950’s, singles had to be released in a 45’ format that held approximately 4 minutes of music, in order to appear on the radio, musicians complied with their contemporary technology. Today we have been handed down the legacy of the history of recording technology and artists still release hit singles of approximately this length not because of technological necessity but out of what has become a standard format of time.

Thinking about time and temporality in exhibitions in the same way creates ground for the speculative exercise of “Standard Exhibition Time.” Although cases of experiments in temporality of exhibitions are plenty, and a huge range of models exist outside of the typical duration, it is still possible to describe the natural time of exhibitions and to recognize deviations. The more an exhibition deviates from this standard, the more likely it is to be held within an independent space, a student exhibition, or to be encapsulated within the idea of an artist as an artwork in itself.

In a report from 2002, the department for policy and analysis of the Smithsonian Institute lists duration as a key element of exhibition design, but does not articulate which duration is appropriate. These dry and managerial analyses recognize duration as an important factor in the exhibition’s effectiveness, but the answer to how long an exhibition should be seems so obvious that little thought or writing is put into even recording the present standard of the institutional exhibition. While there is no clear technological or technical limitation as is the case in the music industry, it is possible to speculate on the origin of the three to four month exhibition based on the history of the curatorial role.

The curator, originally from the Latin verb curare was a “caretaker” of objects in a collection. Unlike today, when the curator busies herself with the communications with living artists, the commissioning of new works, and the budgetary restrictions of these projects, the traditional role of the curator was much more entangled with that of archivist, restorer, and art historian. Could it be nothing but a coincidence therefore, that the recommended length of exhibition time for archival material and fragile paper borders between three and four months? This formula based on the chemical sensitivity of paper to light exposure is calculated on the basis of the relative deterioration of objects under the duress of “exhibition conditions” relative to the benefit of its being displayed. While this connection is only a speculation, it could indicate that it is the very chemical composition of objects which have enforced their time onto our professional tempos.

Is this relevant anymore? While a nice nod to the power of objects to manipulate us into their own demands for eternal preservation, contemporary art no longer has the same needs or restrictions. Some projects which have been successful attempts to question and break this tradition include Fatos Ustek’s Fig 2 at the ICA in London which saw an opening each week for an entire year. Later, she founded Art Night London which institutionalized the ephemeral format suitable to performance and site-specific production. The radical experiment in the most recent Oslo Biennale questions the biennial format by prolonging the project through a string of invitations and events in public space over the course of five years, questioning and experimenting with new temporalities.

Today, as we move further into a time of “biennialization,” we have already seen the challenging of this popular temporality in various forms. In the biennials that present themselves as the most relevant and up-to-date, the timing which is standardized and enforced by its very name, has now become a standard to regularly refute. In the accelerating speed of the art world we now see the normalization of constant events, lectures, and workshops dotting the time between biennial exhibitions, because, in the furore of capitalist artistic production, not visibly producing is equal to death.

The purpose of this thought experiment is not only a challenge to curators and cultural actors to think deeply about why we do the things we do, but also a stepping ladder towards radical new formats. Tradition is a comfort that is easy to adhere to from stances of insecurity. This is an important notion to understand where we are today as a collective, as well as imagine how our formats will evolve in the unfolding future.

End.

This essay is part of a series of special features for the exhibition ‘1-31’ curated by Adam Carr.