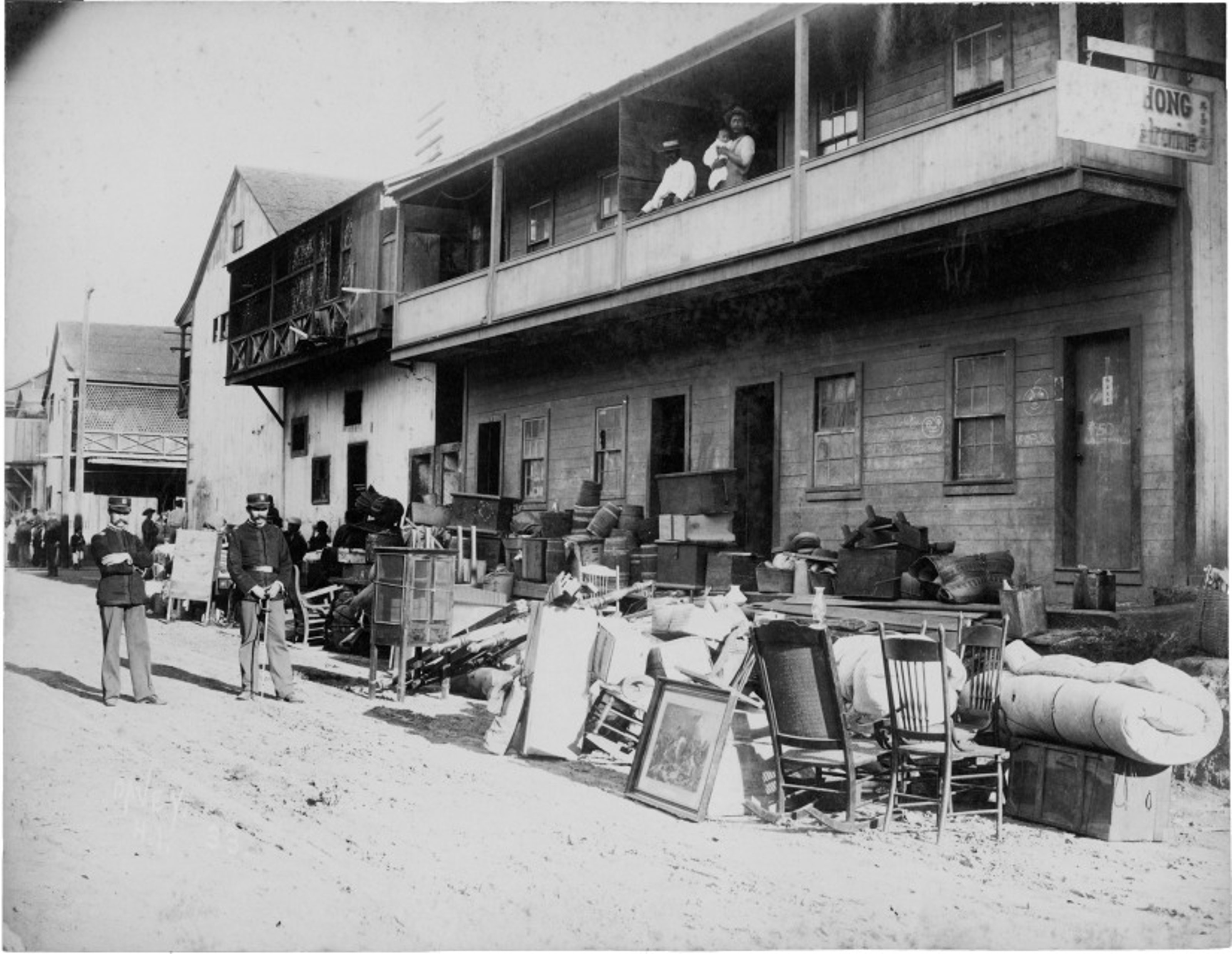

Quarantined area of Honolulu’s Chinatown.

This article is the third installment of a collaboration between Collecteurs and Working Class History, a project dedicated to bringing to light the everyday actions of citizens; the working class. As much of history is written by the powerful and the wealthy, Working Class History aims to highlight the struggles of the unheard, to enlighten and impact the world of today. Check their , follow them on and listen to their .

Honolulu Chinatown Fire of 1900

On 20 January 1900 health officials in Honolulu, Hawaii, trying to fight an outbreak of bubonic plague attempted to conduct controlled burnings of homes and businesses in Chinatown which quickly got out of control. The fire accidentally set light to the wooden roof of the old Kaumakapili church, then continued to spread for 17 days, devastating an area of 38 acres, including 4000 homes of mostly Chinese and Japanese residents.

Authorities disregarded evidence that rats spread the disease, and instead scapegoated Asian residents for the disease which had killed a Chinese bookkeeper. They based their tactics not on science but on racist stereotypes about Chinese homes being dirty. So they set up a cordon sanitaire, effectively quarantining people of Asian descent in the city for weeks.

Their possessions were thrown out into the street, their homes sprayed with carbolic acid, and they were forced to shower in public in mass, makeshift cleaning stations. Officials then began burning the homes of Chinese and Japanese people.

Residents of Chinatown under quarantine.

When the January fire first started spreading out of control, residents fleeing for their lives were turned back by the National Guard, backed up by white vigilantes. Eventually a single exit in the cordon was opened to allow people to escape the fires.

The Honolulu Advertiser declared that “intelligent Anglo-Saxon methods” had been employed to combat a “disease wafted to these shores from Asiatic countries”. Another local paper celebrated the fire for supposedly eradicating the plague while also clearing valuable real estate.

After the fire, many of the residents made homeless were never able to return to live in the area, and its demographics were permanently altered.

Racist scapegoating of Asian-Americans continues to this day, with the far right and US President Donald Trump attempting to rebrand the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus”.

Honolulu Fire, 1900, Gabriel Bertram Bellinghausen via Wikimedia Commons

Bath Riots of 1917

On 28 January 1917 Carmelita Torres, a 17-year-old Mexican maid who worked in the United States, refused to take the mandatory gasoline bath given to day labourers at the border, and convinced 30 other trolley passengers to join her. Her protest spread in what became known as the “Bath Riots.”

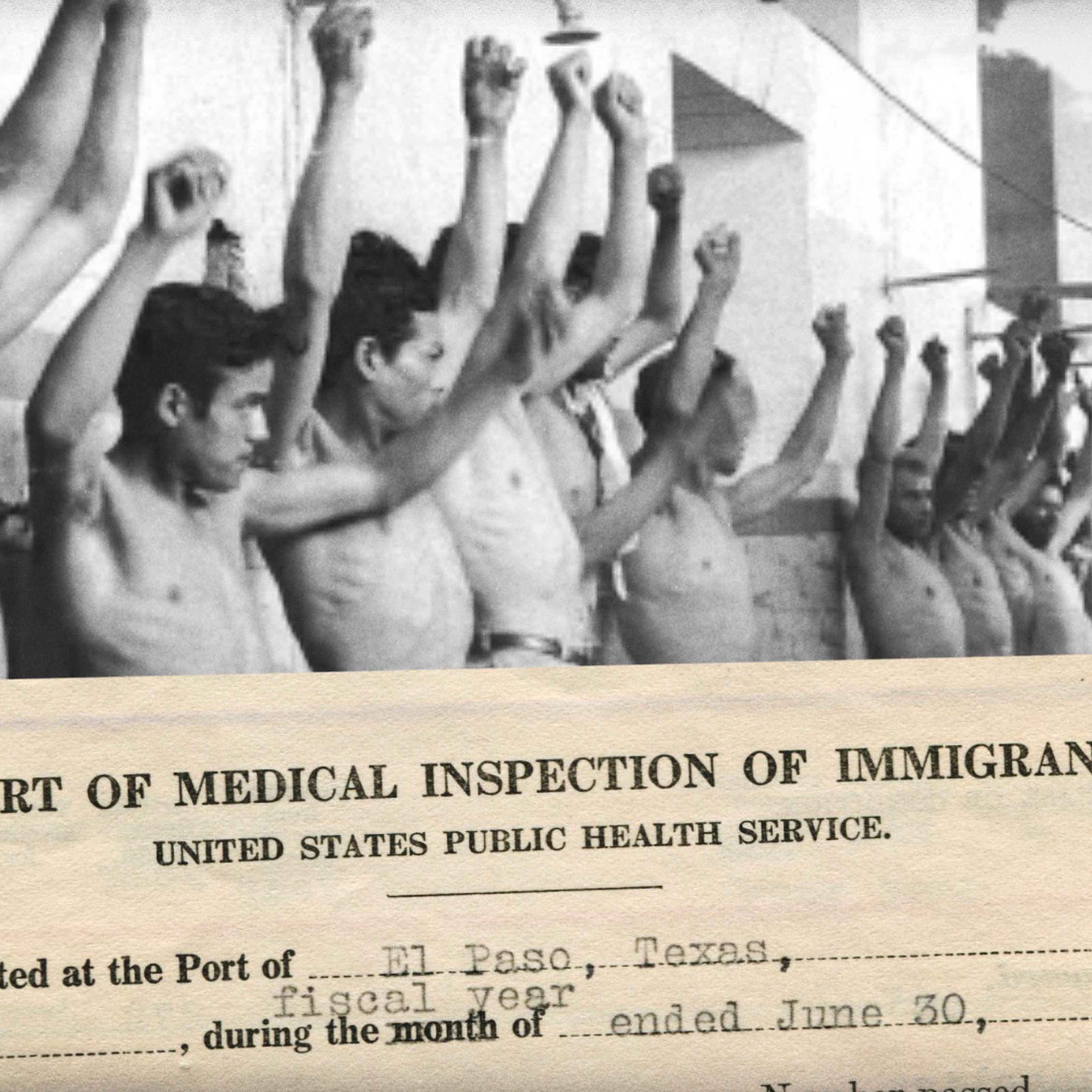

Torres was one of many workers who crossed the border between Juarez and El Paso each day. In the name of public health, Mexican workers were frequently subjected to degrading and humiliating treatment.

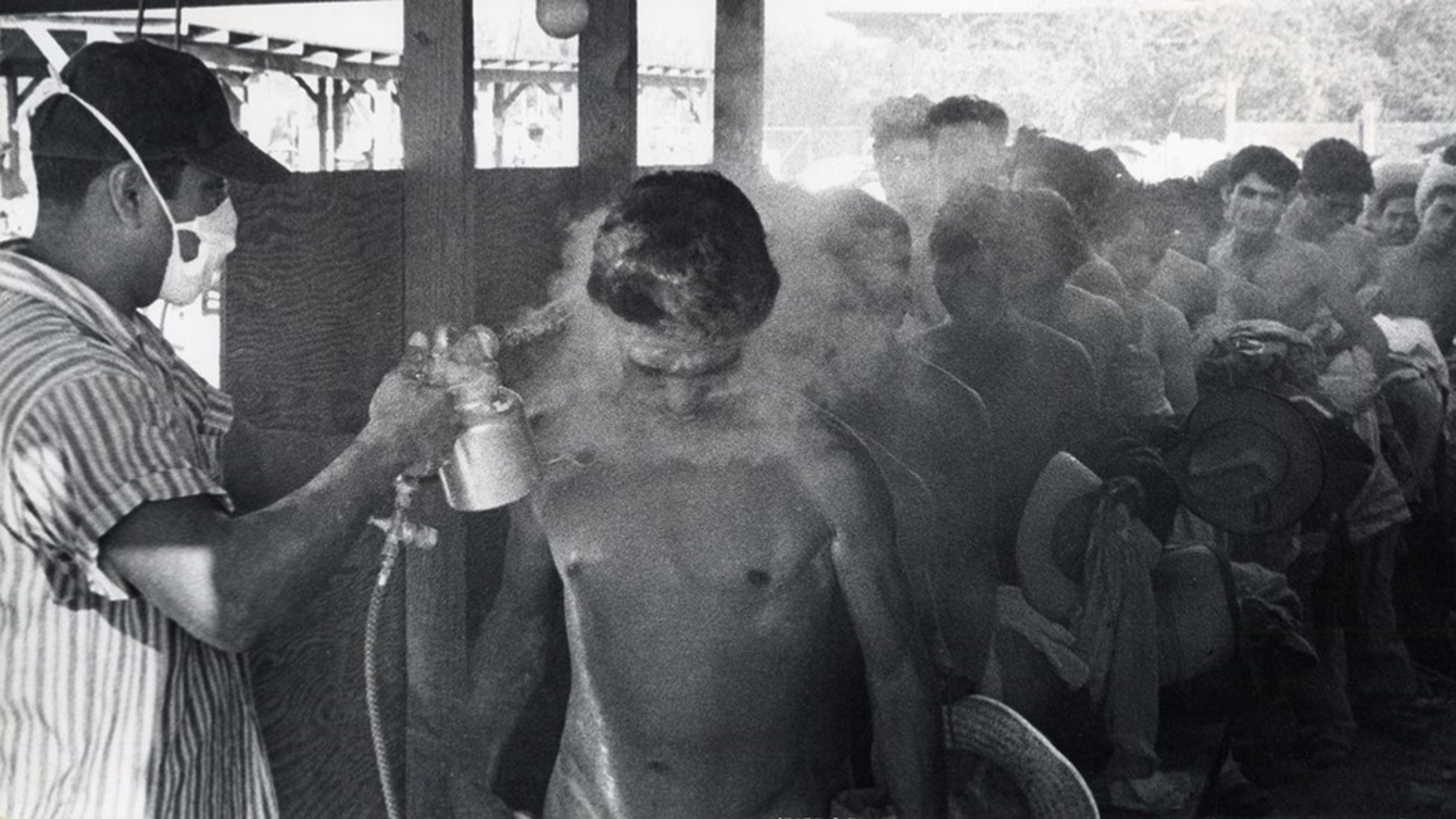

They had to strip naked, brave, undergo a toxic gasoline bath, and have their clothes steamed. The stated aim of the programme was to kill lice, which can spread typhus. However, it was not applied to everyone crossing the border: just working class Mexicans.

Mexican workers sprayed with toxic gas when crossing the border.

In addition to gasoline being poisonous, it was also a deadly fire risk. A group of prisoners in El Paso being treated with gasoline were burned to death in an accidental fire. Furthermore, US health workers were secretly photographing naked Mexican women.

Anger at the practice finally exploded, and within a few hours Torres had amassed a crowd of several thousand mostly women protesters. They blocked all traffic and trolleys into El Paso. They pelted immigration officers with rocks and bottles when they try to disperse them, and when US and then Mexican troops arrived they received the same treatment.

The riots were eventually suppressed by the soldiers, and Torres herself was arrested. This appeared to have the effect of discouraging future protests.

El Paso Newspaper, 1917

The enforced bathing and fumigation of Mexican workers with toxic chemicals like gasoline, and later DDT and Zyklon B, continued until the 1950s.

The use of Zyklon B at the border appealed to scientists in Nazi Germany, who in the late 1930s began using the agent at borders and in concentration camps for delousing. Although notoriously they later used it to exterminate millions of people in the Holocaust.

End.

This article is part of a series of special features for the exhibition ‘1-31’ curated by Adam Carr.