On August 28, 2015, at 3.33 pm Khaled Barakeh posted seven photos showing six dead children on his Facebook account. All of them had met their death in the Mediterranean. Under the title “Multicultural Graveyard” Khaled’s posts, as he wrote it, ran: “Last night more than 80 Syrians and Syrian-Palestinian asylum seekers have drowned in the Mediterranean close to the Libyan shores trying to reach Europe.” These images, censored by Facebook, ultimately changed the way the West viewed immigration.

Anne König: Where did you find these photos?

Khaled Barakeh: Since the beginning of the revolution in Syria, as a kind of alternative way of making things happen on the ground, people have been organizing themselves in groups in Facebook to have a place to meet and plan events away from the eyes of the Syrian regime and its spies. One of these groups was created by some asylum seekers so that they could help each other find the best way to get to Europe through Turkey and Greece. One of the guys from this group, which has about 200,000 members, posted these images, and, without thinking for too long, I decided to repost them on my Facebook page.

AK: What is the Facebook group called?

KB: It’s called “Immigration Garages for the Displaced.” It includes a team of twenty volunteers called “Rescue and Follow-Up” who follow refugees from their starting point until the moment of their arrival in a safe haven. Members of the team are continuously present throughout the day on the group page. They communicate with the refugees via WhatsApp to make sure they are safe, and, when necessary, they contact the coast guard if the boat engine has stopped or there’s been some other problem.

AK: Khaled, your post crossed between two cultural realms—the Arabic-speaking world and the English- speaking world. Was there a moment when you were thinking, should I or shouldn’t I be posting these images?

KB: I saw them and my immediate reaction was to repost them. Of course, I try to be sensitive about what I post because once I posted a harsh image from the Libyan revolution and a friend from Denmark had a strong reaction to it, asking me why I would post something like this on Facebook! I understand that we live in different realities, if not parallel worlds, but how can we help form public opinion if we don’t show reality as it is? Think about the image from Vietnam taken by Nick Ut in 1973, The Terror of War—the little Vietnamese girl who was running scared and naked, and how much it changed the attitude toward the American war in Vietnam. That’s why I thought that these images should be seen. I also think the title of the album and its description added something to the story. It kind of opened a discourse, a call for people to wake up and to see this. In her book Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag says, “Remembering is an ethical act, has ethical value in and of itself. Memory is, achingly, the only relation we can have with the dead.”

AK: You mentioned that you did a selection of images. What was shown in the other images that you didn’t post?

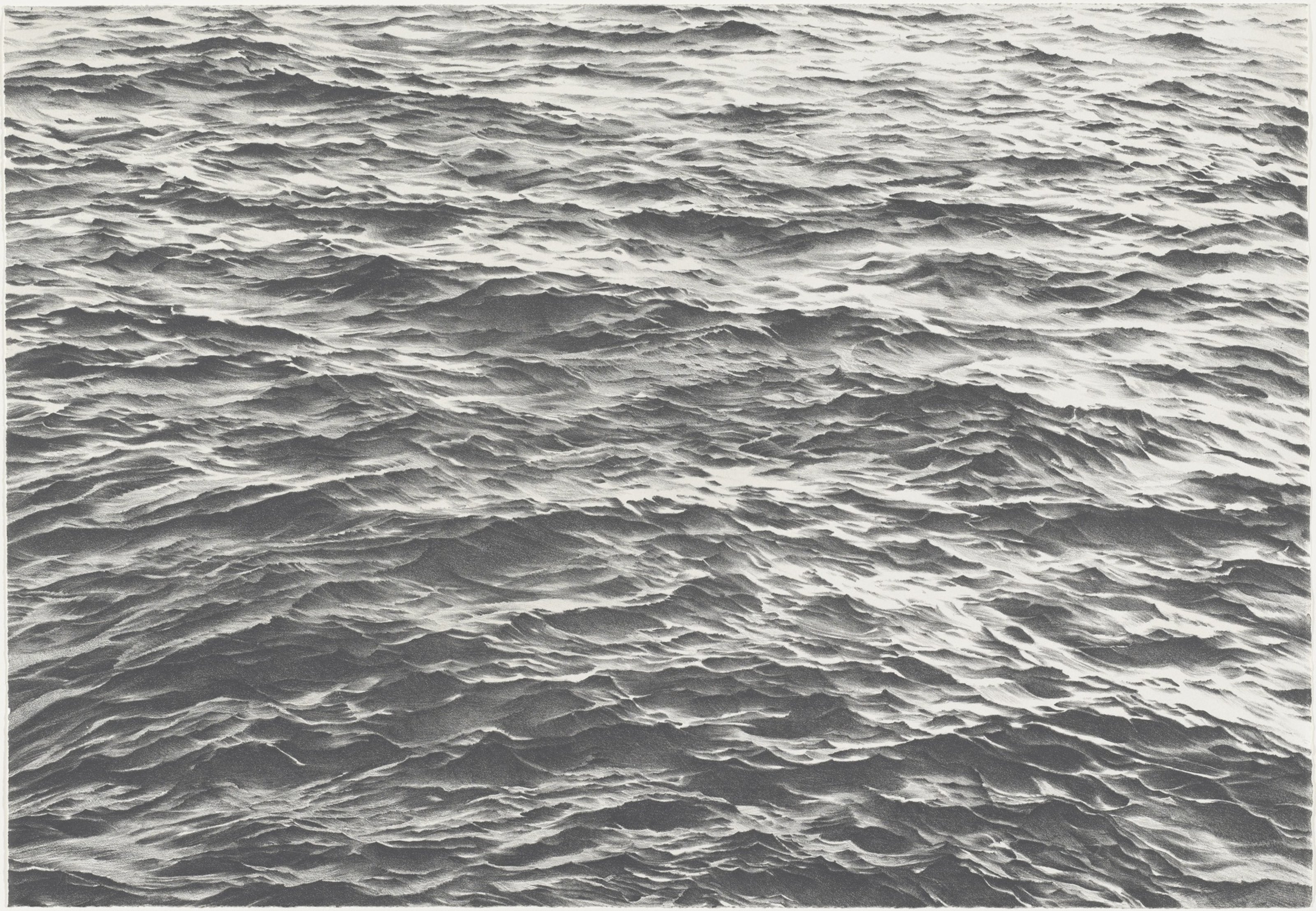

KB: There were a few more images, but in some of them you could recognize people’s faces, or the bodies were in very bad shape. There were also photos of adults, but I took the ones of the drowned children where you don’t see their faces. Just to save their dignity. I tried to be responsible about what I was posting but I didn’t think twice about it. I titled the album “Multicultural Graveyard” because I think that the Mediterranean is becoming the biggest graveyard in the world, as a lot of people from all over the world have drowned there, especially from the southern part of the globe. I found a description of this tragedy in Arabic that I translated into English and posted together with the photos, but later I figured out that the text had some mistakes. I discovered that the story was different from what I’d first read.

AK: How did you find out the story and what did you discover after you had posted the “Multicultural Graveyard”?

KB: When I posted the images I didn’t expect them to get that much attention from all over the world. A lot of newspapers, both national and international, contacted me, wanting to know what exactly happened that night, where and to whom. But because I didn’t have the facts, I didn’t respond, but instead I decided to start my own investigation by searching the ocean of Facebook images to come up with some solid information.

I traced the photos from one profile to another trying to get to the source. To the person who was standing on the beach that night.

AK: What was the aim of your research?

KB: I wanted to know what the real story was, as well as to find out who took the photos! Later on I discovered that the boat started its journey from the beach at Zuwara in Libya heading toward the shores of Europe! It had around 470 people on board, and more than half of them drowned. Some volunteers from the Libyan Red Crescent tried to save the ones who were still alive, while documenting the death of those who weren’t so lucky. They took photos of the dead bodies and samples of their DNA for the ones they couldn’t identify.

AK: **Why do you need to know who was on the boat?

**

KB: Because these people have names, faces, and stories that must be heard, and I feel it is my responsibility to do this! It’s like finding a baby in a basket at your front door … You can’t just close the door and ignore the fact that it’s there. Also since that date, if you search my name on the web, you’ll find my photo side by side with the images of the drowned children.

I still don’t know what exactly happened on that journey and I want to know! So I decided to go to Libya to find out more. I’m now in contact with people from organizations in Malta, Libya, and Italy, and with some locals from Zuwara in order to figure out what happened during the night of August 27.

AK: I remember that I saw your post on the evening of August 28. Three days later, all the images you’d posted disappeared. What happened?

KB: On August 31, after it had been shared over 140,000 times, many people who had shared the photographs noticed that the link had disappeared from their timelines, including myself, of course. I didn’t receive any notification from Facebook as to why they had all been deleted, even though I wrote them asking for an explanation! However, after many newspaper and websites commented on it, a Facebook spokesperson told mashable.com, “This content was flagged in error by our systems as spam, and we have since corrected it. We apologize for the temporary removal of this content.” They stated that the album had been deleted due to an internal bug. However, by making this mistake and playing the role of censor, Facebook drew even more attention to the images after they put the album back. Writer and professor of media, culture and communication at NYU Dr. Nicholas D Mirzoeff wrote, “With close to one billion users, Facebook is, like it or not, the public square in this fraught moment of globalization. In particular, it is being used extensively by refugees themselves and by those seeking to help them. We now need to find ways to hold them to appropriate standards for this vital resource and to agitate to make sure such censor- ship is not happening elsewhere.”

AK: I remember that people on Facebook responded immediately. I also felt cheated because I wanted to show the images to a friend, but then I couldn’t find them anymore. So I got into the public discussion of censorship on Facebook, which I followed with a great deal of interest.

KB: In the album itself, and in each picture, there are thousands and thousands of comments and sub-comments. I also received hundreds of messages in many different languages. Some people thanked me for posting the images because “I opened their eyes” and “everyone should know” and “I changed the world,” while others blamed me for doing that and told me “to go to hell” or asked “how can I dare to post such images online?” or “what if they were my children?” etc.—all kinds of things. Some people wrote me long texts privately describing their opinions, which I found very thoughtful.

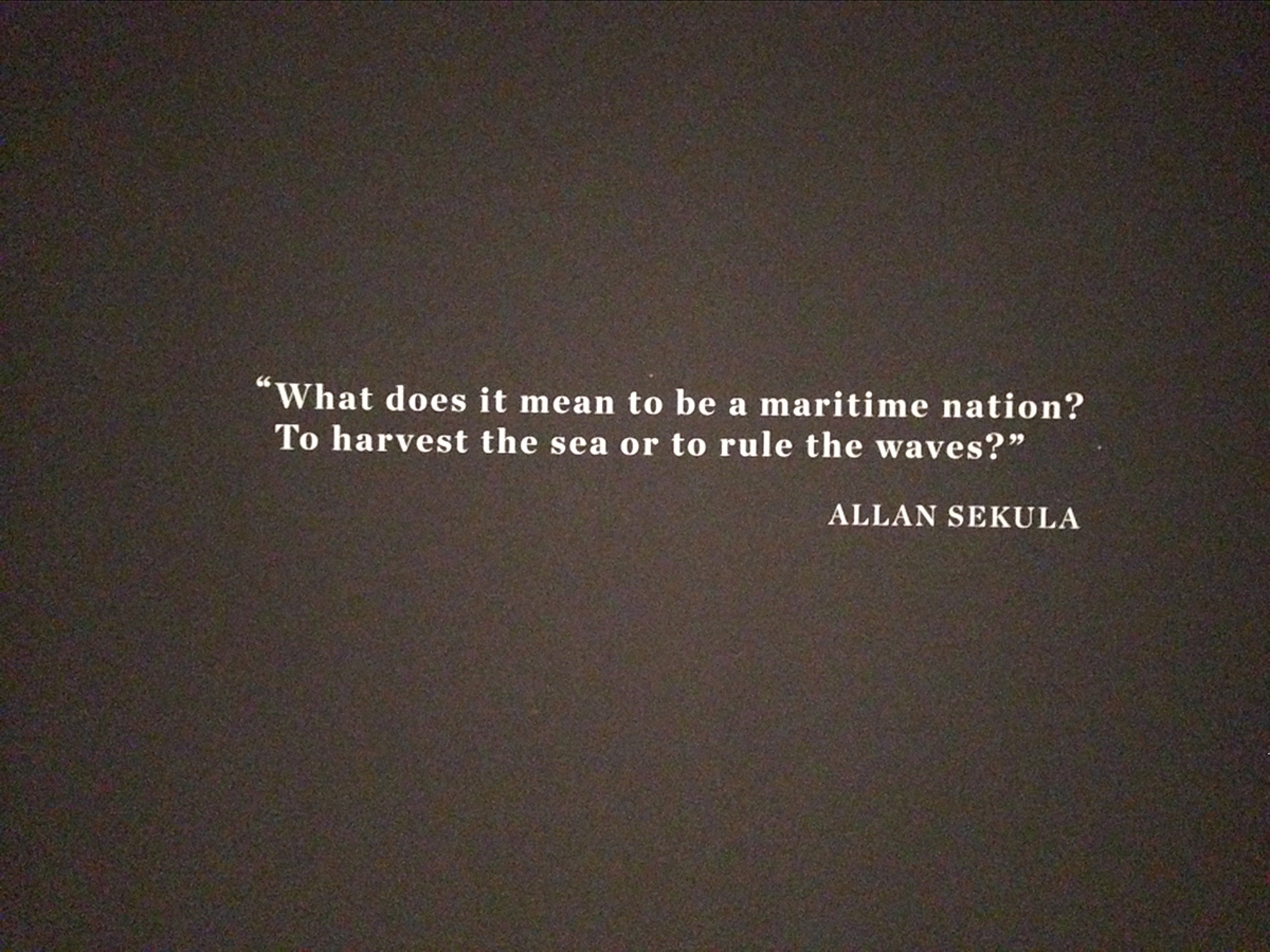

The controversy, from both sides, became a substantive debate where people raised interesting questions: Should, or shouldn’t, such images be seen? What is the role of photography in our modern mass media societies? What are the community standards in social media—and who has the right to decide these standards? Aren’t our values and cultural standards different anyway? Why should the ethics of a company such as Facebook force their capitalistic values on everyone? The answers indeed were no less important than the questions, which prompted me to think about collecting them all and make a book, written collectively, about how we deal with images in our contemporary societies.

AK: It was September 3, 2015, when the photo of the dead Alan Kurdi, the child who drowned on the Turkish shore, was published internationally—you could find this image on the cover of all the major newspapers. There was a big discussion about whether newspapers were allowed to publish such things—should they or shouldn’t they print this photo—but then the whole conversation disappeared very quickly. The problem I have with this is that it’s so focused on one single shot. But there are so many others. And I actually think it’s so misleading to have only one image when there are so many other children and adults dying at sea. The single photo is always a simplification, a cutting-out of a part of the reality, and it denies the rest of what’s going on around. So I found your post much more effective and closer to reality than the image of this little boy. I remember how long I was staring at each of these seven photos. One child who was already ten or eleven had a diaper on. The diaper was soaked with water and when I first saw it I couldn’t make it out properly. It took me a moment to understand why this girl was wearing diapers. The reason was quite simple: they didn’t know how long they would have to stay on the boat and they hadn’t got a toilet there. Every image spoke to me and gave me a strong impression of what’s going on, on the other side of the Mediterranean.

KB: I don’t think the images I posted were taken by professional photographers, which makes them even stronger and more real for the viewer. Personally I don’t like where we are at now with photojournalism, particularly war photojournalism! The aesthetics of photos make death prettier and more acceptable. Look at any international press and photographic agencies: the editors and photographers want to make a bigger impression or be more artistic, with the result that photos lose their function of delivering reality as it is. Susan Sontag, in her book On Photography, says, “Although photography generates works that can be called art—it requires subjectivity, it can lie, it gives aesthetic pleasure—photography is not, to begin with, an art form at all. Like language, it is a medium in which works of art (among other things) are made.”

I think we are drowning everyday in thousands of irrelevant images that leave our brain doped. So photography must be shocking to cut through this anesthetization (the image of Alan Kurdi, as an example, and all the reactions that followed). By the way, I agree with you that it is only a single shot, but I am happy nonetheless that one, at least, finally got into the international newspapers! Otherwise we would have continued our death in silence, as we have over the past five years. Also I don’t think that the image of Alan monopolized the refugee crisis but rather became a symbol of it (like many other iconic images in history). What really matters is to keep the subject present in the political discourse.

AK: But a lot of newspapers did not publish the full image. Very often the Turkish policeman who picked the boy up off the ground was cut out. You could only see the little boy looking like he was sleeping on the beach.

KB I see your point but at the same time it doesn’t really matter, because the photo was circulated around the world anyway. Even right-wing newspapers weren’t able to ignore it and published it the day after. And it was good, it was a call for people to wake up; and that’s why it made a difference, even if it was just a single image. The whole attitude toward refugees became completely different. We really had a turning point between the time before that image appeared and after. Also look at the other side, the survivors; I’m happy for them. They reached a point where a lot of people sympathized with their cause. Germany, for example, took in one million refugees, which wouldn’t have happened if those images hadn’t been made public.

AK: **Why this image and not another?

**

KB: I can’t really answer that question but I will try to analyze the photo: we see a dead child alone on the beach. No past or future (no parents even), only his death is present. He is the final result of a war where it doesn’t matter anymore who is fighting whom. The position of his body tells his story: his head points to the sea, and what’s beyond it, while his feet are pointing to the land where he came from, and his little body stuck in the middle. In an isthmus.

He is wearing jeans and a red T-shirt like any other child. His face is down where we can’t see his features. We can’t tell if he is Middle Eastern, European, African, or Asian! He could be the child of any of us. Everyone can identify their children or themselves with this image.

Also there is the contrast between his death and the vitality of the beautiful beach and the blue sky. Finally there is this authority guy, the Turkish policeman standing on the beach, writing notes about his short life. Taken all together, these things make it very strong, because it’s very peaceful, this image.

From Colophon: Published in conjunction with the 7th Festival for Photography f/stop Leipzig

This article has been reprinted with permission.