Nowadays, we live in a world where our value is determined by how productive we are; where our time is considered useless if not spent in the dizzying pursuit of progress and profit.

In her book How to Do Nothing, author, artist, and Stanford professor, Jenny Odell, writes that with “24 potentially monetizable hours,” society wants us to believe that we can no longer justify spending our time doing nothing. “It’s too expensive,” she says.

How is it even possible to turn our backs on the system? The key to living meaningful lives, she says, is to “resist” the forces that are constantly vying for our attention. And just as the Greek philosopher, Diogenes, did, “neither assimilate to nor fully exit society; instead he lived in the midst of it, in a permanent state of refusal.”

Here, we are in conversation with Jenny Odell, alongside a selection of Gabriella Torres-Ferrer‘s works that focus on the stream of media content by which we are constantly surrounded.

How did we arrive at this state of 24/7 productivity?

I think there are several factors. The first is economic: more people are experiencing less job security — so you might have someone who works two or three gigs, and who can’t afford to think of time outside of productivity. There are also folks in the media, where using social media becomes a part of how they make their living. On the design side of things, the way certain platforms are designed encourages us to think in terms of output and evaluations, where the number of likes on a post can be seen as a sort of rating. There, we’re encouraged to perform and package our leisure, beyond just experiencing it. And below all of this I think there’s the undercurrent of the Protestant work ethic, where Americans feel it’s immoral to waste time, even if you have it.

Why does it feel so impossible to escape it for so many?

For many people there may be no current escape. Someone who is constantly doing the math–in terms of hours, money, and their own ability–just to get by can not reasonably be asked to think outside the framework of “time is money.” Then there are people who might be able to escape here and there, but find it difficult because so much of our culture is geared toward having something to show for your time. In that case it may feel just scary and unnatural to try and view yourself and your time differently. That’s something that’s exacerbated by social media, but it’s certainly not new. I really think it comes down to feelings about mortality. If we view our lives as products that we add achievements and features to, it supposedly protects us from thinking about the potential meaninglessness of our short existence on this earth.

You aren’t simply arguing against the use of technology; this is something deeper, right?

I think it’s important to remember that technology is a really broad term. It gets vilified these days and becomes shorthand for things like social media or surveillance, but technology is also a bicycle or a pair of binoculars: an extension of the human body that allows us to do or see something we couldn’t otherwise. There are plenty of examples of technology that let us see more — for example, into the stars, or into the cells of an organism — and could help us feel more connected to and invested in the physical world. In the book, I give the example of the app iNaturalist, which lets you take photos of plants and identify them, something that can completely change your experience of walking down the street. If there’s anything I’m arguing against, it’s a specific sliver of technology that is commercial and cynically designed for short attention spans, producing and running on alienation.

What’s the way out?

For me, the way out is both simple and profound: it’s just awareness–of oneself, others, and the environment–driven by earnest curiosity. This is why taking a pause, even a brief one, is so important — to actually refuse something, rather than react in a habitual way, takes a lot of attention to the thing it is you’re trying to refuse. It’s possible, maybe even useful, to become morbidly curious about social media and advertising. For example, if I’m forced to look at or listen to ads, I sometimes imagine them as the ads that someone wrote a long time ago for a dystopian sci-fi novel that’s set in the future (now). You can begin to look around the supposed boundaries of the question. This is part of the reason I’m so inspired by the phrase “I would prefer not to” in Herman Melville’s “Bartleby“: it doesn’t comply, but it doesn’t refuse; it illuminates an entire space around the question itself.

End.

Artworks (in order):

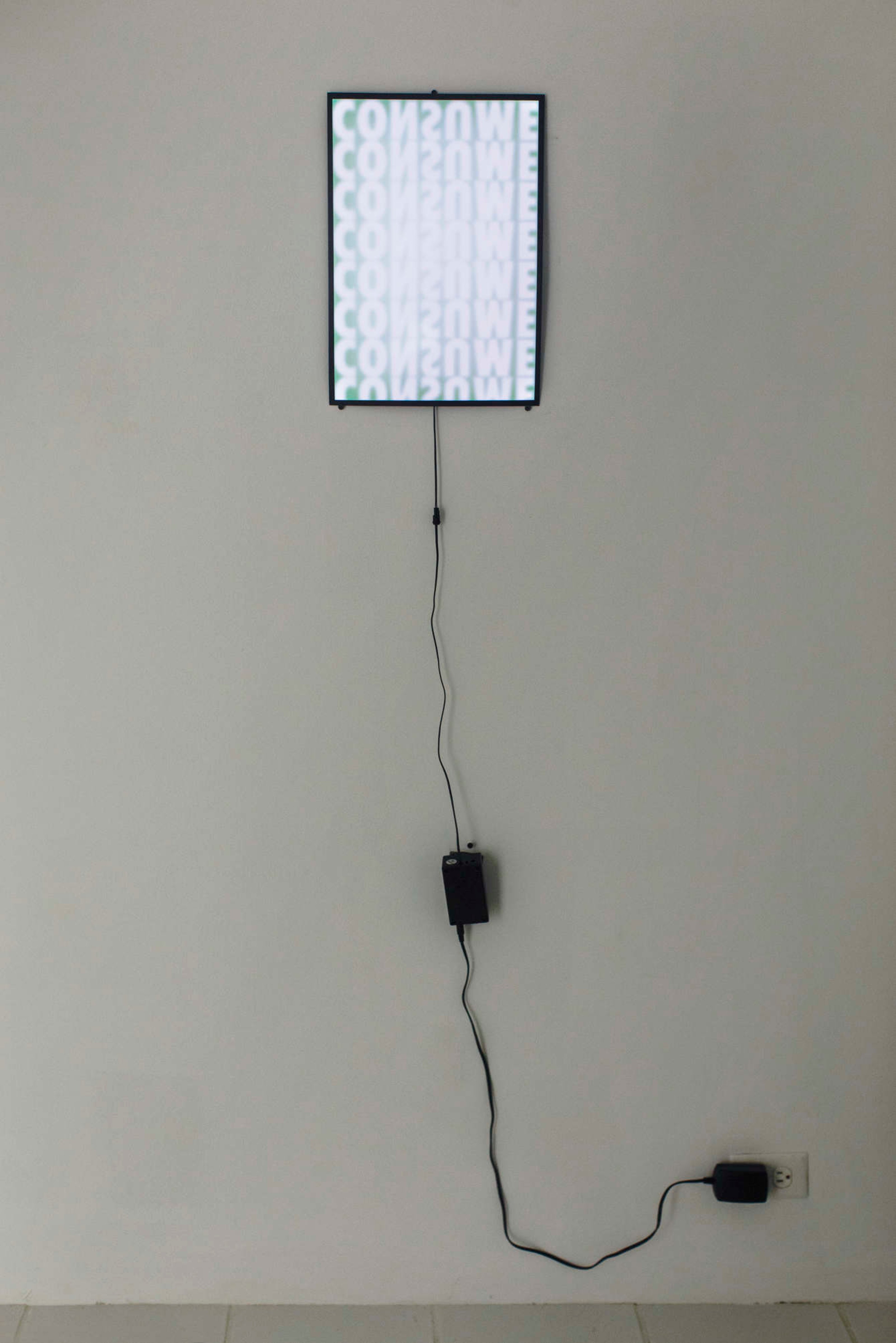

Gabriella Torres Ferrer – Consuwe from the series Untitled (Advertise Here), 2018 (electroluminescent LED panel, electric cord and plug)

Gabriella Torres-Ferrer – Vida Silvestre from the series Untitled (Advertise Here), 2018.

Gabriella Torres Ferrer, Auditoría (Totem), 2018 (15 suspended stainless steel leg cuffs) Courtesy Embajada Gallery.