Our world has changed significantly within the last few months and along with it, our understanding of passing time. As our concept of time gets jumbled up, broken and repaired every day, we try to hold onto either smaller details, or look for solace in the sublime.

Artist Mungo Thomson is no stranger to thinking about time on a vast scale, as his series of Wall Calendars takes the viewer out of the grid of the calendar to the infinite planes of geological time. Here we talk about Thomson’s time in isolation, his opinions on the shutdown period, why he prefers gallery shows and how his works resonate with him now.

Can you describe your working conditions now since the quarantine?

Each day is different. Today I went to a bronze foundry in the Valley where I was looking at the patina on some new sculptures. We wore masks and practiced social distancing. Then I drove to the home of a project manager for the LA Metro Art program and proofed color for a mural I am doing for a subway platform downtown. We stood in her front yard and held the prints down with rocks. It was unusual. But things feel so frozen, it’s good to see some projects moving forward. And when you drive around LA these days the freeways are empty and the air is clear.

Have you set up a routine?

Not really. I set up a big table in the garage and I move things around on it. And I go into the studio here and there. I’m trying to think of this time as a chance to work on longer-term projects, but my wife and I also have to tutor our kids. So even if I wanted to be on my usual studio schedule I couldn’t be. I am normally pretty 9 to 5 but now there is 100% work/life overlap so most days I feel lucky if I get anything of my own done.

Has your relationship with technology changed since the quarantine, now that we rely on it more for social contact?

For myself, not a great deal. I can mostly get by with a laptop and my phone and a notebook. But helping my kids with their “distanced learning” has introduced me to Zoom and Google Classroom and Kahn Academy and Scholastic and Noodle and IXL, and that has been its own special hell.

Do you find your concept of time to be the same as it was before? Has it slowed down/sped up, is it less rigid, less monumental, or more so?

In my work I often apply anthropological or astronomical perspectives to cultural activity – so I’m trying to maintain perspective. I’m very lucky to be able to work from home. This is an incredible global event, probably once in a lifetime. And I was born to stay home. But a lot of people are suffering, and it feels very open-ended. So there is a wading-through-syrup quality to life now. And it’s hard to focus. I feel like I have already lived several lifetimes. There was the week of home repair, and the week of making collages, and the week of doing yoga, and the week of playing video games, and the week of drinking whiskey and being depressed. It’s boring and anxious, but then I remember the expression: Doubt may be uncomfortable but certainty is absurd.

artwork: Mungo Thomson – Mail, 2013. Installation view at Gallerie Frank Elbaz. Courtesy the artist.

How do you feel about the idea of pushing for increased productivity during this time of crisis?

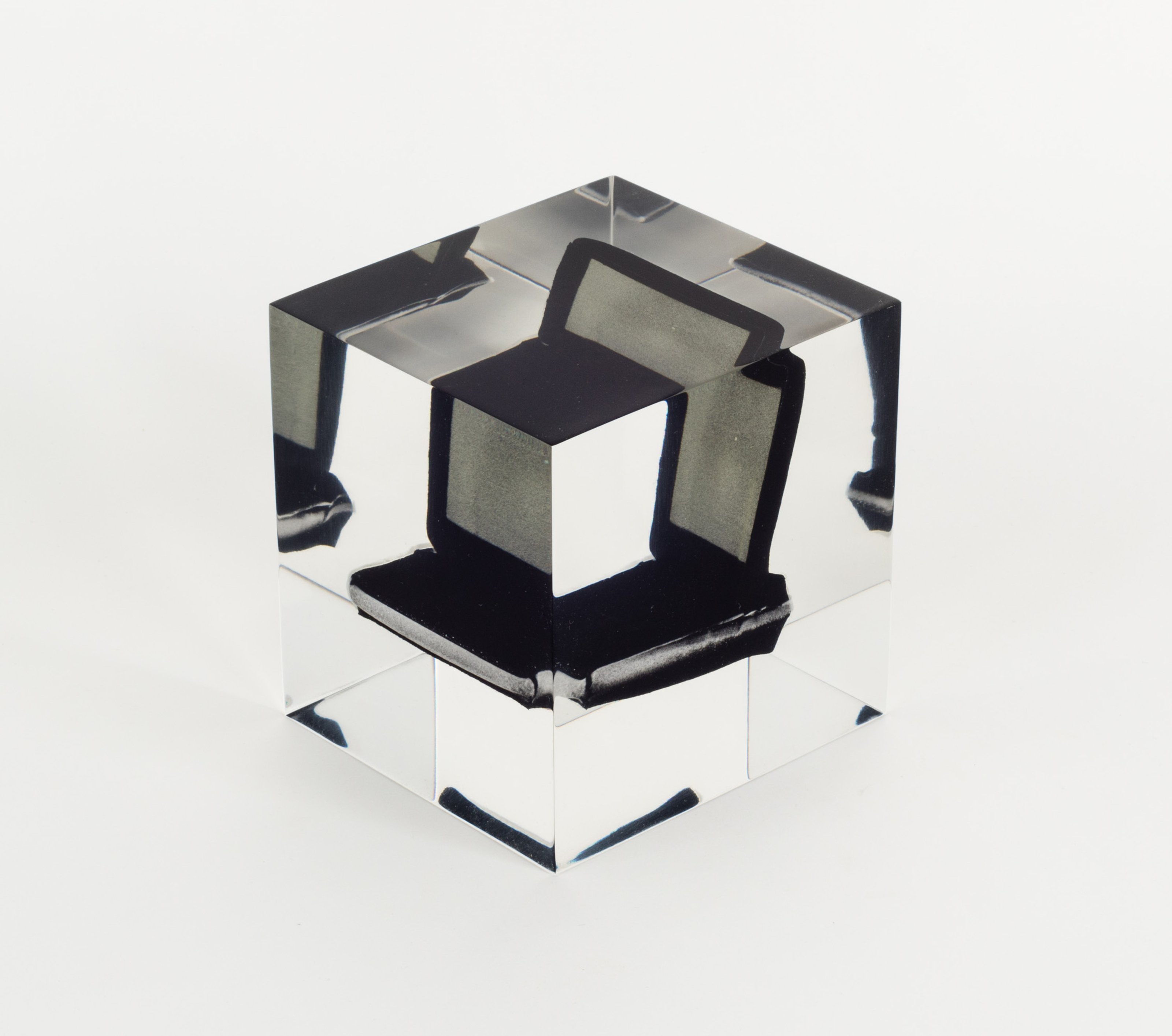

I think we should probably all take the hint and take a breath. I’m trying to think of the shutdown as an opportunity to work on some projects in video and sound that I’ve been neglecting because they need a lot of time-intensive attention that I haven’t been able to spare. But like I said it’s hard to focus. I have a project called Mail, which asks the host institution not to open their mail during the run of the show and let it pile up in the gallery. When I last did it at the Hammer Museum, there were about 5,000 items in the pile, and after the show we photographed each one for a book. Before the quarantine we were hustling to get the book done for the Printed Matter Art Book Fair, but then that was canceled, so this has been an opportunity to sweeten and refine it and make it perfect. Because what’s the rush. Likewise I patched a hole in a wall with like five coats over a couple weeks and got super fussy with it.

Mungo Thomson – Stress Archive (Laptop), 2014-18. Courtesy the artist. Photo by Shane Rivera.

What expectations do you have for when the shutdown is over?

There needs to be a New New Deal. If you didn’t see the importance of universal health care or meaningful political leadership before, COVID-19 has made it painfully clear. As far as the art field, I think a lot of artists would like to get off the art fair hamster wheel so we can focus on our longer-term projects, and maybe this is that opportunity. For me, I look forward to working on gallery exhibitions again. I like to work at that scale, and unlike both the fair and the museum an art gallery is free. Anyone can walk in. It doesn’t mean they do, but the potential exists, and I always thought this meant art should be accessible and democratic. I would like a return to more of that: more gallery exhibitions, and more democracy. But with gallery attendance falling before the coronavirus, you have to wonder if we’re just in a new attention-span regime now and there’s no going back. Maybe the shutdown will flip that around again, and people will explode out of their homes determined to see works of art in person in galleries again. But the longer this lasts the more it’s just training us to live completely online.

Your works are intimately related to the passing of time, marked moments, calendars, publications and chance. How have your ideas around these themes changed since the quarantine started?

What I would say is that certain theoretical ideas I have around the reception of these works have sort of figuratively come to pass, in that some of them imagine a world without humans in it, and the shutdown has made that world easier to imagine. Like I made a work for digital player piano that pairs a deck of 52 cards with the 52 white keys of the piano, and a computer shuffles the deck over and over, and the piano plays these shuffles as sequences of notes. And the math on a deck of cards is such that it should be able to play without repeating for trillions of years. And when you make a work like that you wonder who/what might be around to see it, should it survive. Likewise my new Snowman series, which are stacks of trompe l’oeil Amazon boxes in painted bronze, were meant to be my idea of outdoor sculpture, sort of monumentalizing this temporary tower on your doorstep that you come home to sometimes, just making it durable and weatherproof and permanent. But now they feel like public art for a depopulated world.

Mungo Thomson – Wild & Scenic California 2019 (September-December), 2019. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Shane Rivera

Your work World’s Greatest Mountains 2019 (March), 2019, is a large lightbox work that juxtaposes the front and back of a page from a wall calendar, with an image of a mountain on the face and the month of March 2019 showing through from the back. It is a testament to the sublimity of geological time and how much smaller and how constructed our systems of time look in comparison to their long enduring existence. How do you reflect back on that work now? Is there anything different in your thinking?

When I was developing these lightboxes I was reading a lot about geological time and mass extinction, not in an apocalyptic or nihilistic sense but in a Saganist sense of seeing human endeavor in scale with deep time and the cosmos. And what you come to is the understanding that the record of human civilization will ultimately be strata in rock. A stripe on a mountain. And this layer will contain all our art alongside all our pollution, everything we ever made. To me this is not so much depressing as beautiful and humbling, and somewhat outside perceptual comprehension. Which incidentally is another way to describe the sublime.

artwork: Mungo Thomson – Snowman, 2020. Installation view at Frieze Projects. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy the artist.

End.

This interview is part of a series of special features for the exhibition ‘1-31’ curated by Adam Carr.