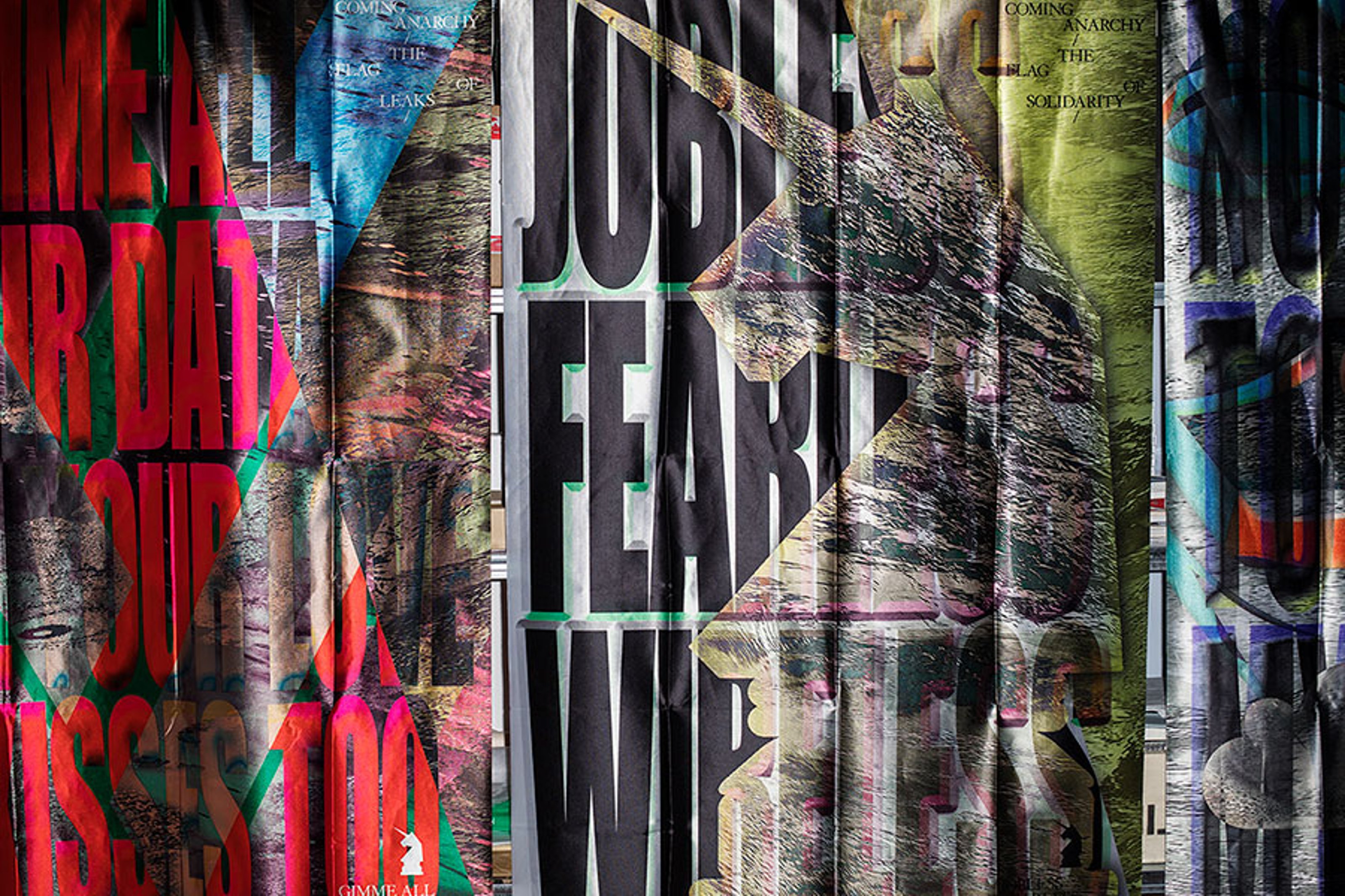

The artist collective, Metahaven, led by Daniel van der Welden and Vinca Kruk, works primarily with writing, design and film. Considering their approach as “critical design,” Metahaven investigates concepts of post-truth, transparency of institutions and accessibility in the age of the internet. In 2004, Metahaven created the visual identity of the Principality of Sealand, the off-shore sovereign nation which played an important role as a data haven during the “dotcom” boom and in 2010, they created the new visual identity for WikiLeaks. Now with exhibitions at MoMA, ICA, London, MoMA PS1 and Stedelijk Museum under their belt, they continue their groundbreaking, yet subtle, future-forward practice. Their published books include Uncorporate Identity (2010), that tackles the issue of the role of design and authorship in a consumerist society and Digital Tarkovsky (2018) which investigates the human experience with smartphones by tracing what cinema, storytelling and time mean in our platform-based world.

Published during the COVID-19 epidemic in 2020, Collecteurs co-founder, Evrim Oralkan began the conversation over email after Metahaven opened exhibitions at the ICA, London, and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, during late 2018. In 2019, they met in NYC again after Metahaven’s opening at e-flux, and walked through Manhattan’s Lower East Side talking about art.

Evrim Oralkan: I know your main objective is not to educate the public, but your work is very effective in informing the viewer while also creating transparency. What is it that you would like to achieve with your work?

Metahaven: With Collecteurs you are striving for transparency within a system—the art world of private collections—that is, by definition, anti-transparent. And you are striving for transparency within a medium—art—that is itself opaque. One of the ways in which art is necessarily opaque is in art telling a story that’s irreducible to being something else. The part of a work that’s actually “art” cannot usually be reduced further to something else that it is “about,” because it is that thing already. Increasingly, what we want to achieve with our works is a story, or a sensation, that’s intrinsic to them. Something non-descriptive and non-realistic.

Metahaven – Eurasia (Questions on Happiness), 2018

I watched Eurasia four times in a row. The first two times were about learning and only during the last two times was I able to meditate on the various topics presented. In a way, I was watching, but at the same time I was going deeper into some of the subjects. So in my case, you certainly achieved what you hoped for. Exhibitions like Islands in the Cloud at MoMA PS1 and Version History at ICA London allow you to reach wider audiences. What are some of the positive outcomes that could come out of this sort of exposure?

Watching a film four times in a row is only possible where and when there is the kind of affordance that makes duration not an obstacle. We don’t have to worry about the general availability of online and offline moving images anymore; the mere availability itself is not the point. We don’t need to worry about art adapting to a Netflix mentality. Hence, the logic of exposure does not really work that way in our opinion; it is not as if the bigger the stage the bigger the affordance.

Would you say the main purpose of Metahaven is to take action on political and social issues?

We wouldn’t say that. We’re skeptical about our own work’s abilities to directly affect social and political change, and especially for any art to be instrumentalized with the purpose of effecting such a change. We say this not to belittle any of the beliefs, hopes, desires and goals involved in contributions in such a direction. We see in our work somehow a form of abstract reporting—somehow absorbing and transforming the conditions of making into the work itself—and less so an instrument that achieves measurable external effects. To act in a situation with no way out is as difficult as can be. And every action, for sure, is always, in some way, the wrong one. There are no reasonable or balanced ways to be right. Being right is a form of being wrong. Political acts are acts of necessity. If there is a link between art and politics, it is there.

There is a recent shift towards moving image in your practice. It seems to me that the viral YouTube format and easy-to-understand narrative of Eurasia is very impactful. What was the catalyst and purpose for this shift?

The shift isn’t that recent if you imagine that we started making music videos in 2014. Doing so meant becoming immersed in the emotional flow of time, which created new feelings and a new kind of process for us. We started drawing and writing scenes and involve environments and atmosphere, becoming interested in cinematic texture. We went there because it reflected who we were and were becoming as people, it was about where our lives were leading. Lyrical poetry, as well as absurdist poetry became strong influences. We came to really like the aspect of production, and the collaborative side of it.

You successfully marry enlightening knowledge with appealing aesthetics. That being said, the style, subject and narrative of each work is different. What is the common denominator that binds them together?

Acknowledging the difference that exists between the works is kind of important for us. Eurasia opens with multiple iterations of its own beginning, the first being a reading of “I know the truth,” a poem by Marina Tsvetaeva, the third being a reading of sentences from treatises on the truth by Émile Durkheim. Information Skies has the question “who knows what’s true? who knows what’s not?” answered. While one of the two Hometown protagonists says:

Here is where we disagree, where one and one

makes three.

Because I say so, because it’s me.

But when one and one makes three

because it’s the decree that says so

that’s not me!—says who?

And is that so called

law that different

from a law that says that one and one makes two?

In Eurasia, there are several design elements that suggest “rewinding” and counter movement. What are you pointing to?

To playheads pointing backwards, to forgery and manipulating historical narratives. We tried to invoke questions about the changing relationship between Europe, Russia, and Asia. We paint the picture of a political geography and system that is on the verge of being, quite literally, consumed by its own obsession with a (largely invented) past, as has been the case in Europe. Think also of architectural megafictions like the über-kitsch neo-classicist plastic renewal project of the city center of Skopje, Macedonia, a country which was recently renamed into North Macedonia.

It certainly feels like the world is running backwards sometimes. Do you foresee that a people’s movement could create a better future for all humanity in the post-capitalist era or, as you mentioned in Eurasia about Lars Von Trier’s perspective, is humanity going to be punished for the damage they have done to the planet?

This is posing a challenge for art. Art does not, in a material sense, contribute to a solution, and at the same time does not operate independently from these problems, or outside their consequences. What is very interesting about poetry, for example, is the minimalism of its ecological footprint in relation to its ends, the enactment of art with and within the listener. You can collapse artworks into poems and poems then are like a .zip format for art as a whole.

In 2004, you created the visual identity of the Principality of Sealand, the off-shore micronation which played an important role as a data haven during the “dotcom” boom. In 2010, you designed a new image for WikiLeaks. Are there any exciting new collaborations we should know about?

After Sealand (2004) and WikiLeaks (2010), we collaborated with Independent Diplomat, and in 2016 attempted to do so with Sea Shepherd. That was the last collaboration of that kind for us. At the moment we are making our new film Chaos Theory, and preparing two new film works, one of which will be a single-channel music film and the other a film cycle. We are contributing to an art publication called Art Worker. We’re working on a conversation with the filmmaker Jazmín Lopez and are writing for a new book. We’ve also just finished a new strand of textiles. There are several collaborations underway too.

I think what makes your practice so different and unique is that you do not have an interest in being a part of the art market. Do you take any measures against your works becoming auction highlights one day? Is it possible to keep your works from being commoditized?

The effectiveness of Collecteurs is in part in recognizing that art is a commodity and it does so both within and outside of the strenuous environment of the art market. Thus you are interested in its opposite: art that doesn’t care about the art market. The question we would like to ask though is about collective and collaborative survival and about the privilege that one can have in declaring oneself “independent” or “outside” of anything. “Keeping one’s work from being commoditized” is a purposeful action vis-a-vis a commodifier, and the art market is by far the only source of commodification that currently exists. We are interdependent, not independent.

The majority of our moving image works are not on the internet, and probably won’t be. This is for a reason; one of the last ways of having a sense of agency over one’s work as an artist is in being able to at least co-decide on the platform of its display or dissemination. The film’s mode of display is part of its content. So in that way we are defining what the commodity of our work is.

What are the main benefits of being a collective?

We can learn together, let off steam to each other, and help each other.

Finally, I must ask, what can a straw do besides being used for drinking?

For us, this question, coming from a drinking straw manufacturer in Eurasia is a central philosophical dilemma. Like, what is the value of a thing aside from its function? In a sense, he seems to be pointing at a kind of absurd, childlike key role of art, an emotional surplus that he would like to unlock within an object . It’s a beautiful question, we think. Besides being used for drinking, a straw can be looked at. Or it can be abolished, as the EU has done with plastic straws.

This interview is part of a series of special features for the exhibition ‘1-31’ curated by Adam Carr.

End.

Interview by Evrim Oralkan

Photography by Christoph Mack for Collecteurs

Illustration by Berke Yazicioglu