Back in 2013, after three years of non-stop contemplation, César Cervantes decided to sell the collection of contemporary art that took him two decades to build. It was a radical decision by one of Mexico’s most avid art patrons—one that was not taken lightly.

With the proceeds from the sale, the ex-collector bought Luis Barragán’s Casa Prieto-López (now christened Casa Pedregal) with the hopes of preserving part of his country’s heritage. Little did he know though, the challenge of residing in one of Barragán’s most iconic residential projects and the pressures he would come to realize from the world that had, for so long, embraced him.

Once in his possession, Cervantes invited his friend Jorge Covarrubias, co-founder of Parque Humano, to convert the house back into Barragán’s original design, and make it habitable for his family. The house’s former horse stables were turned into _Tetetlán_—an intimate cultural center consisting of a restaurant, library and yoga space intended to introduce a sense of community to the neighborhood Cervantes had lived in from the age of seven.

Ever since officially exiting the contemporary art world, Cervantes has received a continuous wave of criticism from almost everyone in his immediate vicinity. From artists to collectors and gallerists, feelings of betrayal and abandonment have largely dictated Cervantes’ newly chosen life. Only a handful of the people he had come to know and appreciate throughout his time as a collector, defended his decision to sell and walk down a different path.

Some years ago, you were considered one of Mexico’s most avid collectors. Then the moment came when you decided to sell everything. With the proceeds from the sale of your collection, you bought and restored Luis Barragán’s Casa Pedregal. Why did you sell your collection?

Collecting art was part of a material manifestation. I wanted to learn, evolve and cultivate myself. I never collected artworks for physical, material or economical pleasure. I collected lessons; paths that would open and amplify—sometimes stretch—with every piece I bought. Every artwork, including the collection itself, merged music, literature, philosophy, psychology, even spirituality, all into one element.

Collecting—very much like its etymological meaning suggests, ‘accumulating lessons’—taught me a lot; some of the lessons are the best ones of my life. It also opened the path to understanding detachment itself, and not to contribute to situations that wouldn’t be positive for our community.

Neoliberalism, sustained within the economic market and its principal idea, is almost a synonym for corruption and imbalance. Just like it is for consumption and excess of production. All of this has been permitted for more than 20 years inside the art world. The majority of artists evolve into some type of businessman/woman, rather than into intellectuals; art fairs have stopped being discreet and have turned into rigid nightclubs, kermesses, malls and runways for fashion and status. Museums have started to surge like castles and cathedrals of their time. They’ve become mere gigantic symbols of social and economical imbalance.

I just didn’t want to participate in it anymore. Not that I could have learned everything I learned while collecting somewhere else. I discovered too much about its system. It was the opposite of what culture had taught me, and keeps teaching me every day.

Can you speak a bit about your collection, which artists it consisted of and when you started to get rid of it?

I’ve been interested in culture all my life, I even thought about studying art. At some point, I thought I’d be able to participate even further within the setting of culture without becoming an artist. This is likely what led me to collecting; it was 1994.

At the beginning, I mainly focused on Mexican masters like Rufino Tamayo, Jose Clemente Orozco, Rafael Cauduro, and other artists that were part of the new visual arts generation.

It wasn’t until 1999, when I assisted for the first time at FIAC, that I realized what I had done in terms of collecting and how it had developed. It was also there where I saw the work of On Kawara for the very first time, as well as a Mexican artist no one was willing to acknowledge or to collect: Gabriel Orozco.

Through Kawara, I was introduced to visual arts and other cultures starting from the 50s, and through Orozco and his ‘Friday Workshop’ I got to know even more about my own country. The point of encounter for both was Marcel Duchamp who, still today, continues to act as the rector in my life. I also started to collect and admire the work of Goya, and works of other young artists.

How did things continue from there on?

I would regularly assist international fairs. There would be moments I would even travel to Europe or Asia just for one night, so I could present exhibitions and biennales. That’s how the collection continued to evolve naturally.

Just now, during these past few days, I finally realized the breaking point: Art Basel Miami Beach, in 2002. Just the way it has been a huge business for the organizational company and the city itself, I think it also represents the start of collecting’s banalization, and, above all, its consecration to the system of neoliberal capitalism.

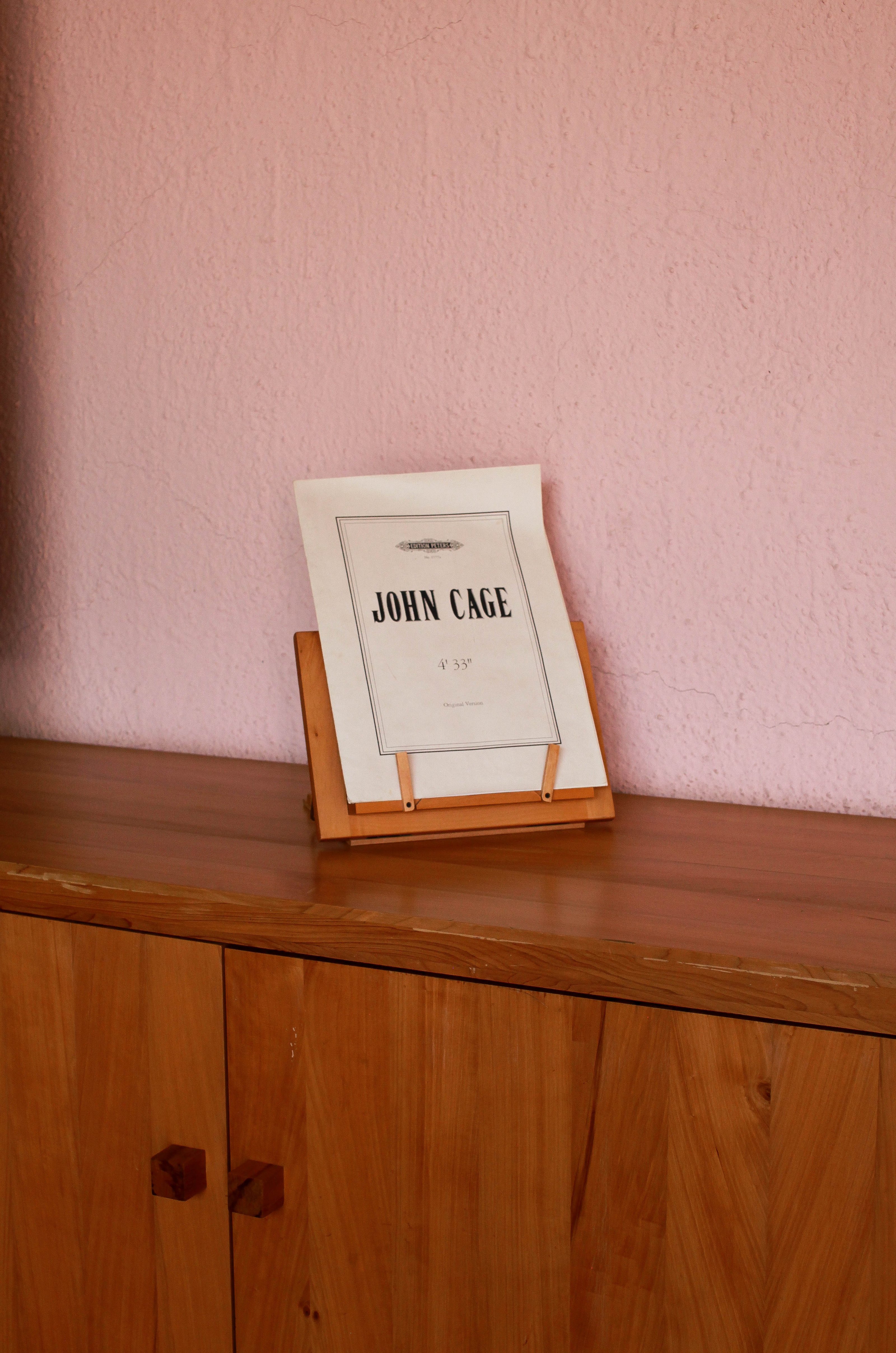

Ever since then, everything within me began to change. The hyperinflation of prices and careers of young artists prevented—or at least made me question—if I should buy their work; so this change was harmful, but also helpful in many ways. It inherently resulted in me starting to collect ‘forgotten” masters; like Duchamp, Goya, André Cadere, Rietveld, Bruce Nauman, the early works of Andy Warhol, Robert Filliou, John Cage, Alighiero Boetti, and others.

Starting in 2002, I would commission site-specific art for the house or city I lived in. This was another great channel that taught me about the nature of art—how it needs to be visible and public, and not be stored away inside storage spaces or other private conditions.

The last and wonderful turning point was getting to know the work of Jimmie Durham, and form a relationship with him. After our project in 2007, “Still Life With Sprite and Xitle,” I realized it would be difficult to do something else as a collector. Today, I think it was the peak of my change and fortunately, soon after, I began to recognize that it was the beginning of the end. It was actually during this final period that I committed most of my mistakes, merely stemming from my discomfort and having made the decision to stop collecting.

In 2011, I made the decision to stop. I took care of some final previously-engaged commitments. The dissolution of the collection began in 2013. It was the most critical, criticized and questioned moment in my life, but at the same time, the moment I learned the most.

I let go of my collection, every piece of it, with the same love and passion as when I found, acquired and lived with it.

Which works did you keep?

I couldn’t choose one piece over another. There were some works that were of extreme value to me, but all of them were part of a joint decision. I decided not to keep anything.

How did the Barragán house happen?

Casa Pedregal had been for sale for many years. I actually offered it to many collector friends in and outside of Mexico. But, for whatever strange reason, no one would buy it. Since I’m deeply committed to the neighborhood I’ve lived in all my life, as well as my culture, I eventually decided to buy the house and restore it the moment I sold the majority of my collection.

Back then, and still today, I believe there’s an overflow of production in art and architecture. I thought it was better to preserve one of the most important architectural works in Mexico, instead of being one more collector.

An anecdote actually comes to mind, which explains some of the things I’m trying to say here: About a year ago, a prestigious Irish, US-based American artist came to see the house. She showed little interest for the house’s architecture or its history, yet was very interested in what I had paid for it. Once she learned the house’s value in today’s market, she answered: “Not that I want or need the house, but it’s basically equal to 3 or 4 paintings of mine. So if you feel like it, we can trade one day…”

Aside from everything else, there was also a genuine impulse to lead a more spiritual life with less possessions, less attachments.

Could we read this decision of yours as an actual form of protest? Were you trying to educate people in some way? Education is not really the right word, but were you trying to somehow make people aware of the art world’s superficialness?

I don’t protest, I merely act according to my principles and beliefs. When I stopped buying contemporary art, I just wanted to stop participating in an environment that was so far from my own beliefs. I wanted to be more congruent with my life.

Since I’ve never believed in education, I never thought I could educate someone. My good friend Ajo said it well, “I started learning when I left education behind.” Or, like Einstein, who said the only problem with his learning was his education. I only did what I thought was best for my community and myself.

Before and after your collecting years, did you feel some kind of responsibility towards the artists and institutions you inherently supported?

I’ve always felt responsible for people in my environment, not just artists. Artists don’t need support, that’s a myth; a practice anchored in the renaissance. They’re big companies, great businessmen, and the government manages their publicity and communication. That’s why artists are continuously supported by programs as incredibly neoliberal as FONCA (National Fund for Culture and Arts).

An artist doesn’t deserve any more support than a carpenter, a doctor, a restaurateur. If they come to the point of needing support, it should come from the very inside of their community. Meaning, the artists with the gallerists—between them, there is so much money, like in any other sector.

I worked a lot with well-known artists and galleries. We had fun and learned a lot from each other. I would do my part, and they would do theirs, and that was a way of mutually supporting each other. I’ll always appreciate if I positively helped the career of some artists, or the consolidation of galleries.

What have you learned by officially giving up your existence as a collector of contemporary art?

I learned that the economic system is merciless, and that money rules in today’s society. I also learned that in many situations you’re a friend as long as you’re useful. When you stop being useful, you become useless as a person.

I also learned to what extreme people can be resistant to change and reinventing themselves. People live their lives thinking about other people. Reinventing oneself via exploration and widening one’s horizons is a great motor.

Imagine how my life would have been as this big collector… with that fame, that comfort, that label. It’s been such a reward to take the risk and leave everything behind. I’ll be forever grateful for all the lessons I’ve received; before, throughout and after.

What caused this big change of letting go?

The moment was very clear, I realized I couldn’t give collecting what it needed. Though it seemed to give me plenty, in the end it was taking from me much more than what I received in return. The collection and persona around it became more important than me. Money become more important than its actual value; the quantity of time erased time itself.

When did you realize everything? Was there also a part of you that was smitten by the perks of being a well-regarded collector and arts advocate?

It was a long process of observing, accepting and reflecting. I questioned my own comfort zone, and decided to change it.

From the very start I had my doubts, but I decided to do it regardless. One day, the moment came when all of my initial questions returned. The art market was so vulgar and fake that it was easy to make the decision to go down another path.

But doesn’t the art market’s perversion begin with the actual human? In ways, I think the (art) world has become this way, because people much rather live a life of being idolized and loved by strangers than actually loving themselves — meaning, living a life that pertains to a clean(er) consciousness.

The market is a human creation, so everything falls into that. This could be humanity’s worst moment, worse than the world wars we’ve had. The market is racist, imperialistic, sustained by power and ambition, as well as guns.

It’s no surprise that the world’s main country is lead by Donald Trump. Right there [in the U.S.], where some of the biggest contemporary art collections are, where 65 % of the art is marketed, where you have the most museums in the world… the country of ‘instantaneous happiness,’ the country with the biggest consumption of legal and illegal substances.

What were the responses of the artists you collected? I assume most people—artists, museum directors, curators, etc.—immersed in your former world didn’t want to understand your decision, at least not publicly.

Well, there was a demonstration against me. And, sadly, it was lead by people I had been very close with; people who even at certain moments showed off our friendship, people I supported and who had given me a lot in return.

I might have been the very first ‘public’ collector in Mexico or any other country who made this type of decision. Many of them might have felt ‘betrayed’ for whatever reasons, so they decided to treat me like a ‘deserter.’ Religion and politics (great ancestors of collecting) get rid of people who are opting for change or planning to abandon their group of power.

Fortunately, I understood all of that from the very beginning, so I don’t have any resentment, nor the need to pardon anybody. With the passage of time, false rumors are clearing up, and that’s how everything will continue without me needing to say a word.

At the same time, people in the art world who I had considered very close, almost like family, became even greater companions by reinforcing their role as courageous and great friends. The rest, which is obvious, were mere friends of the success; the character, not the person.

Art used to be your passion. Has any of that changed since you sold the collection?

My passion wasn’t art. It was, and still is, culture. When I decided I was going to collect, I knew it was the instrument which would allow me to support the culture of my community.

During the 90s in Mexico, there were just a few collectors of contemporary art, and the majority consisted of locals and nationalists with works from previous generations. Eugenio López is an exception. The rise of contemporary art coincided with Gabriel Orozco’s gallery project Kurimanzutto, which started just a few years earlier.

Today, I also think the house helped in raising a certain kind of awareness regarding Mexico’s heritage, the Pedregal of San Angel, and the preservation of patrimonial properties that belong to my country’s culture. I’m not sure what will happen tomorrow. I just started to look in other directions and focus on tradition and customs, the origins and roots of my culture.

What’s been the biggest challenge with preserving Casa Pedregal?

Living in the house and preserving it has been a privilege and continues to be a lesson every day. It’s literally living in a supreme creation, and I only dare to say so because I had nothing to do with the creation itself. Everything you see here and everything that was, is a creation of Barragán, not me.

The only challenge is to lead a life that parallels the house itself; a life that continuously seeks intelligence, sensitivity, soberness, openness, and serenity.

Was it hard for you to make these changes?

They weren’t changes, but rather, evolutionary processes that came naturally. The hardest thing was to go against such a powerful and evil system.

When we met at Tetetlán, you said nowadays the word ‘artist’ merely applies to ‘visual art,’ excluding musicians, writers, designers. Why has visual art become the sole definition for art? How would you define art?

There is so much more money involved in visual arts. It’s where things can accumulate and where things can be speculated, since it doesn’t require any speciality other than having money in order to buy and participate within the world.

Reading a book or understanding music requires much more time and dedication. The market and technology also allowed for visual artists to expand into video, artist books, sound pieces, fashion, practical products; so much that a writer is still only called a writer, a musician a musician. The term ‘artist’ has been appropriated by the visual creator.

If I were to define art, I would go with a quote that Duchamp said more than half a decade ago: “Art is a game between all men of all eras.”

Why do you think you needed art before, and now you don’t? This reminds me of a quote by Piet Mondrian that you mentioned when we met: “If the human race would reach its perfect state, it would no longer need art.”

I’ll probably always need art in some kind of way, but I think real art isn’t inside galleries or museums. It’s in knowing how to perceive and how to feel and live the everyday. Art, according to Mondrian, should be a way of life, and not a thing that hangs on the wall.

What inspired you to open Tetetlán?

It might sound conventional, but my children Bruna and Lazaro are my world and the basis for all my inspiration. They are my starting point of community and action, and from there comes my interest for generating sustainable projects that allow them and us to live with dignity, equality, and sustainability.

After them, my partner and family, comes my community, which is this neighborhood. Tetetlán is for all of these people. It’s a place where we get to know each other, and where we share and generate culture in all senses—gastronomically, intellectually, physically.

Pedregal is such a wonderful urban project, but unfortunately it’s cut off from the city. We want to serve as a point of encounter, where people can unite. Connection is the greatest form of safety and growth.

Are there any institutions you avidly still believe in? Would there be a gallery/museum model you could have faith in again?

I believe more in individuals than in institutions. Actually, there are people who have become institutions. Like Francisco Toledo, or Remigio Mestas. I get inspired by people and their actions. I could never believe in a conventional commercial model, and even less in those which are sustained by the economic, neoliberal model like commercial galleries.

I’m sure there are very courageous people in the art market that have started to reflect, and perhaps are already on their way to creating new models. But for now, I don’t know any.

What is one of the most valuable lessons you’ve learned while participating within the art world?

Still today, I receive beautiful lessons from the contemporary art world. There are wonderful people in that segment, people who know how to reinvent themselves and—instead of being a banal accessory inside a banal world which strongly contributes to inequality and polarization—actually become part of a cultural detour.

The first lesson that comes to mind, is a quote on culture by Borges, which I adapted to culture and collecting: Culture “_is a labyrinth in a straight line._”

Then there’s another great quote, by Rochefoucauld: _“All passions make us commit mistakes._”

What would you need in order to join the art world again?

Today I’m much more active in the art world and culture. I was a collector and a big supporter, perhaps, at times, even a patron; I received a lot from visual arts and will always be grateful for that. True gifts never come to an end; they don’t stop circulating. Art has been a big gift to me. Now, I prefer to dedicate my attention to the roots of culture.

I don’t think it’s necessary to return to the commercial art world. People have invited me to join very interesting projects, even governmental opportunities. However, I think I can contribute much more to other scopes of art. Apologies for doing it again, but I have to mention another quote, this time by Robert Filliou:

“I am not just interested in art, but in society of which art is one aspect. I am interested in the world as a whole, a whole of which society is one part. I am interested in the universe, of which the world is only one fragment. I am interested primarily in the Constant Creation of which the universe is only one product.”

Don’t you think this idea from the 60s is a such a wonderful thought, and more necessary than ever?

End.

Introduction by Jessica Oralkan

Text by Lara Konrad

(Translated from Spanish)

Photography by Angela Suarez for Collecteurs