The Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (RIBOCA), founded by Agniya Mirgorodskaya, a Russian oligarch’s daughter, has brought significant investments into Latvia’s cultural scene since its inception in 2016. Her father, Gennady Mirgorodsky is a prominent Russian businessman, both a fisheries tycoon working in the arctic as well as developing extractive industries in Siberia. With the outbreak of the ongoing war in Ukraine, the biennial halted its activities but now plans to resume.

In response, Latvian artists Ēriks Božis, Maija Kurševa, Armands Zelčs, and Amanda Ziemele, withdrew from the biennial and local curators and critics have published articles revealing the biennial’s deep involvement with Russia’s oligarch class. RIBOCA recently issued an open letter saying that “In March 2022, RIBOCA ceased all funding from Russian individuals and sources, as well as reviewed and made changes to their board,”1 but this has not convinced local cultural workers that enough has changed.

This interview has gathered active members of Latvia’s cultural scene. Maija Rudovska is a curator, researcher, and writer who has recently co-authored an article with critic Santa Hirša in the Latvian newspaper Delfi.2 They are joined by Žanete Liekīte, a curator who has worked in various spaces in Riga and has also published about the subject in the journal Satori.3 Maija Kurševa is a Riga-based artist who withdrew from the biennial citing the need to resist Russian funds considering the ongoing war in Ukraine. RIBOCA did not respond to a request to include a representative in this interview.

Àngels Miralda: What happened when the first news about RIBOCA appeared in Riga?

Maija Rudovska: If I remember correctly, the news about RIBOCA's emergence was circulating among art circles in Riga internally some time before the biennial publicly announced its first edition. It was known from the beginning that the funding was coming from Russia and that the biennial was being created by someone who was not from the local art scene. Internally, it was also known that the support from Riga council, which at that time was led by a pro-Russian party, was requested by Pjotr Aven, a Russian billionaire who is currently subject to international sanctions. He was amongst the supporters sitting in the same room when Putin announced a “special military operation” in Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

All of these interesting facts back in 2017/18 raised suspicions about the aims of the biennial, especially asking why these people, who are not originally from Latvia, want to set up a biennial in Riga? During the Soviet Union, Latvia and Riga were strategically important places for the soviets due to our ports and infrastructure. Historically, Riga has been one of the central cities in the Baltic region. RIBOCA has done all of their communication not only in Latvian and English which is standard within the cultural scene but also in Russian.

Within the art scene, two different views were taken - firstly, there was criticism from the very beginning noticing colonial rhetoric, which explicitly stated that this event was being presented to Riga as a “gift.” Curator Katerina Gregos, who was selected to curate the first edition of RIBOCA initially was presented as a key voice of the Biennial - more details about this can be found in an interview conducted by curator Inga Lāce.4 Secondly, some people in the local art scene were looking forward to the event with curiosity, knowing that a biennial of this scale could not be organised in Latvia with local funds - and hoping it would bring international attention and audiences, placing Riga on the map of international art tourism.

Àngels Miralda: RIBOCA seemed to have solved these initial issues as there was not much renewal of this discussion in the second edition - what did they do successfully?

Maija Rudovska: The criticism diminished as the local art community saw that RIBOCA was not a one-off event (as some initially thought), it also actively collaborated with local art institutions financially supporting some of their activities, giving the impression that the biennial was successfully integrated into the local art community. In the time between biennial editions the foundation started MicroRIBOCA - a programme of events giving continuity to the endeavour and focused on building collaborations with the local art scene. I think that these activities and presence in the local art life diminished the voices of critics, including my own. And of course, I cannot deny that from this point of view it can be seen as a positive contribution to the local arts ecosystem.

These collaborations, friendships, and contributions to the local environment have also acted as a successful strategy to diminish criticism from those who are not backed by their own money or influence by setting up networks of dependency. We can see that now, in the context of an ongoing war, many people in the Latvian art scene are silent about RIBOCA, or defend it, because they have been closely involved over the years and have benefited from the biennial in some way. I'd like to use a word recently stated by an art friend - we have adopted a new conformism that consists of self-censorship and fear to go against art institutions, people, or processes because of precariousness and the highly unstable conditions that most of the art world lives in.

Àngels Miralda: Žanete, you published an article in Satori recently that addresses these issues. What is different about the situation now than during the first edition?

Žanete Liekīte: The political landscape may have seen an escalation with the onset of a full-scale war, but this conflict traces back to 2014: we were all fully aware of the situation, yet our actions fell short of addressing it effectively. The mere fact that this is already the third edition of the Riga biennial is a testament to our ignorance. From its inception, this institution has been intertwined with Russian billionaires, marked by questionable funding - and I do not consider the explanation in the open letter of how they set up offshore accounts as a resolution to any problem whatsoever - and accompanied by condescending and imperialistic remarks aimed at the Latvian art community.

I wrote the article you mention while working in NYC. Distanced from the reality being addressed, and temporarily liberated from the confines of the tightly-knit art community, I expressed my unfiltered honesty without concern for ruffling any feathers. I didn't love the idea of stirring up this messy dispute around my name, but the passive stance of my own art community became too embarrassing in the eyes of my Ukrainian friends and future colleagues abroad. How can we justify such an event unfolding in our art scene? We fervently rallied for fundraisers to support Ukraine, only to host an extravagant Moscow-art-soirée in our own city months later. This is hardly the solidarity Ukraine deserves.

The ability to criticise this event is now improving. After the recent publications by Santa Hirša, Maija Rudovska and myself, a ray of hope has emerged. It finally seems that there is a fair share of supporters after all, who have managed to grasp the sheer hypocrisy of endorsing toxic philanthropy in the art world. Back in 2018,5 Santa already shed light on the tangled web of intricacies, the response was nothing short of reproach. If someone dared to criticise this event, the remarks were commonly along the lines of: “Oh, so you don't appreciate high-quality art events in your own city?” or “is it envy that drives your scepticism towards the incomparable scope of RIBOCA?”

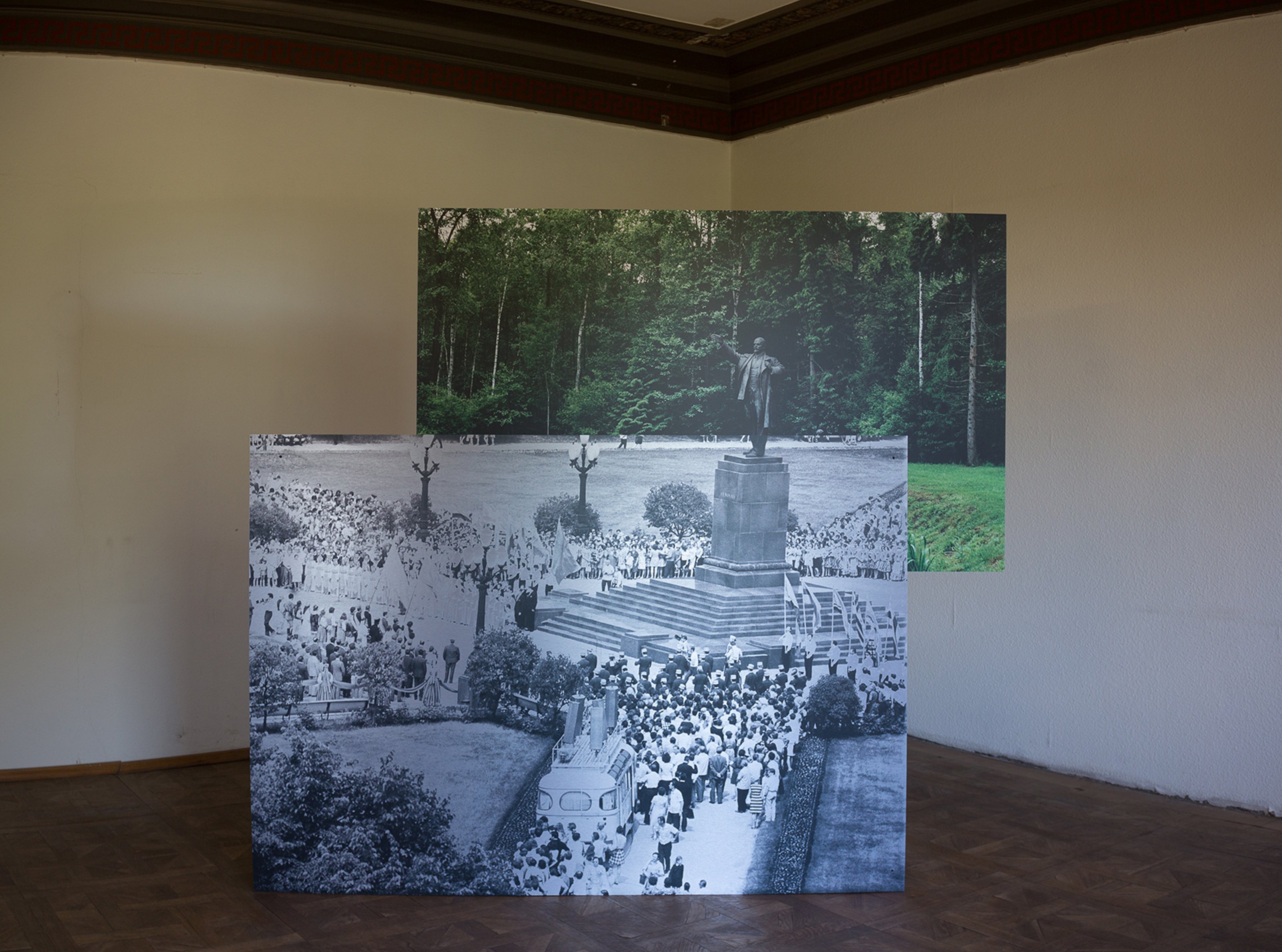

Installation view from RIBOCA2, “And Suddenly it All Blossoms,” 2021

Àngels Miralda: Maija Kurševa, you are one of the Latvian artists who has withdrawn their participation from RIBOCA. Why did you do this? Did you try to change things from within the organisation? What was their response?

Maija Kurševa: I withdrew my participation from RIBOCA because after the 24th of February 2022 our world had changed dramatically and I found it simply impossible to receive money from a Russian business to produce commissioned artwork. When there is an ongoing war, money that comes from the Russian Federation is toxic. On the twentieth day of Russia’s full-scale invasion, I wrote to the curator and urged the team to be transparent and clear, to inform international artists about funding and cancel the exhibition. I suggested we could continue only when Putin is dead or in prison. Now, I would like to add - and when a dangerous Russian empire is disarmed.

The argument given by RIBOCA that money for artist fees comes from other countries, like Switzerland is a calming compromise out of an account department. It is a legal argument but entirely unpersuasive. I think it is important for the organisation to be honest and transparent about its finances and origins. When the war is raging on our doorstep, the fact that the organisation’s money comes from a Russian business and that most of the founders and board members are Russian citizens and no one is Latvian at least should not be a secret. And it is good that these issues are discussed now and will become known outside the Riga art scene.

We had conversations with the curator, I spoke with the team about my concerns and discussed with some of the Latvian artists about funding issues. We concluded that each individual can take a decision based on their personal understanding of the situation. No one from RIBOCA asked me for advice, but I guess the concerns have been heard. Recently Agniya Mirgorodskaya announced that there is no more Russian money, the RIBOCA financing structure has been changed and they promised to deliver a public audit to confirm that. They recognized that “there were artists who didn’t want to participate” and it is “a choice we highly respect.”6

Àngels Miralda: So if the financing structure has been changed, why is this still a problem?

Maija Rudovksa: I personally find it inconceivable that such an organisation can exist and operate freely while there is a war in Ukraine - despite the fact that the biennial supposedly claims that the money is no longer coming from Russia, but the people behind the biennial have not changed. Mirgorodskaya is still the biennial's biggest funder - the fact that she now cites her husband, the American Robert William Pokora, as the Biennale's biggest funder does not change the fact of the matter. Mirgorodskaya's name is added into her husband's company. It's the same money she is now channelling through the United States. It is the same money as that which was in the biennial’s accounts for last year, when they decided to postpone their program.

Àngels Miralda: Santa, I want to ask more about this because the claim that there is no longer Russian funding in the biennial works on paper. So why do the criticisms continue even after the US foundation was set up by Mirgorodskaya's husband?

Santa Hirša: There is no such thing as an opponent of the Putin regime who only became so after the 24th of February 2022. At the moment, many Russians are moving their businesses to the West for personal gain and practical reasons, and this has nothing to do with political ideology. None of the previous RIBOCA editions have expressed messages or included artworks critical of Putin or the effects of Russian influence in Eastern Europe. Even Katerina Gregos, who is well known for her socially sharp art projects, curated the first RIBOCA as a politically correct, neutral exhibition from a Russian point of view, while the second edition even included an artwork dedicated to Putin's main ideologue, Aleksandr Dugin.7 All of this makes me see RIBOCA as an ally of the Putin regime, not a critic, and in Latvia’s geopolitical situation this is totally unacceptable. Thirdly, it is too late to withdraw from Russian funding only now - it should have been done much earlier, because RIBOCA’s brand and visibility has already been built on blood money. If they were really ready to break with the past, they would have to set up a new institution with a new board.

The transfer of the foundation to the US is just an accounting trick, because the founder of RIBOCA and its main patroness Agniya Mirgorodskaya has not renounced her Russian citizenship. Her marriage to a US citizen simply allows her to formally receive the same money through an association registered in another country. This in no way addresses the ethical problems of this funding. This organisation has lied about the origin of their donations before, so I personally have no reason to suddenly believe them.

Àngels Miralda: Was there any attention in Latvian media when you and other artists withdrew from the biennial?

Maija Kurševa: When I decided to withdraw, RIBOCA’s funding structure was not a topic in the media. Žanete Liekīte was the first person to ask me for a comment and she included it in her Satori article.8 My position is no secret to my circles, I have talked, discussed, and explained my decision.

Àngels Miralda: How have other artists reacted within the contemporary art scene in Latvia?

Maija Kurševa: To be honest, I was sure that all Latvian artists would withdraw, but to my surprise that was not the case. Each has their answers and I would not dare to speak for them. From ten invited artists four have withdrawn from RIBOCA, two have contributed to RIBOCA3’s unrealized exhibition magazine, and four artists exhibited their work originally intended for the RIBOCA3 exhibition in Riga at Kunsthal Moen44 in Denmark, an exhibition space established by curator Rene Block.

Àngels Miralda: But hasn't RIBOCA also brought positive changes to Riga's art scene?

Žanete Liekīte: Indeed, RIBOCA has graced Riga's art scene with its fairy godmother presence, sprinkling it with what might be also perceived as positive changes. The biennial has hosted a myriad of acclaimed artists from around the globe, showcasing local talents alongside them and showering them with extravagant production budgets that make European foundations blush in inadequacy. With its lavishness, RIBOCA's budget for a single event surpasses the sums allocated to support the entire Latvian art scene for an entire year. They orchestrate extravagant gatherings, summon international media, and attract the attention of esteemed foreign guests. These are the very reasons why numerous local professionals choose to look the other way. This scale of production is presented as a "gift" as mentioned above, but a gift always implies a reciprocity, which is why I can't share in optimism.

This boils down to ethical questions of funders. A good example is the Sackler trust during the opioid crisis or Warren B. Kanders' tear gas business funding the art scene in New York. Donations from Russia are directly intertwined with the system that is causing the destruction of Ukrainian lives – no possible perceived good can come out of this.

Àngels Miralda: RIBOCA responded to the Russian war in Ukraine by postponing the biennial scheduled for 2022 and refocusing their efforts on the community space for refugees "Common Ground". What do you think of this initiative?

Maija Rudovska: Two weeks after the war broke out in Ukraine RIBOCA set up a non-profit called "Common Ground," which is defined in their homepage as a centre for social initiatives to "provide assistance to those who have lost their homes and have been forced to flee." RIBOCA announced that it will channel the biennial's funds to support Ukraine, but unfortunately, RIBOCA's funding statement does not show any donations, suggesting that the charity centre was used only as a PR tool to divert attention from the organisation's relations to Russia. Common Ground's program is aimed at supporting Ukrainians, but it's interesting that most people who seek support at this centre have no idea about the organisation’s background. It is quite common for Russian oligarchs to use charity to burnish their image and divert attention away from their real activities or businesses. Also Common Ground found their home at Riga City Hall, which is another way to hide the organisation's relations to Russia, because people don't suspect there is anything shady if the name of Riga is used. It’s a similar case with their title “Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art.”

Àngels Miralda: What is the aim of Russian oligarchs when they put their money into culture in Latvia? What do you think they gain with this?

Žanete Liekīte: It's a classic artwashing strategy – to indulge in lavish spending, extend the sphere of one's influence, and divert attention from the serious accusations that tarnish one's reputation. A clever ploy to make people forget or question less, all while maintaining a façade of generous endowment for the arts. It doesn't necessarily render them untouchable, but it does make them noticeably less vulnerable. And these altruistic hiccups are stunts that seem to be particularly convenient to execute in regions with complex histories like Latvia. As Maija Rudovska's commentary, quoted in my Satori article, points out, our post-Soviet backdrop offers a rather favourable and fuzzy ground for these individuals to flex their soft power tactics. Society is divided, there's a shortage of funds, and until now, it seemed like nobody would raise any objections. It's rather disconcerting, but these well-intentioned mishaps are still managing to slip under the radar, as we can clearly observe.

Àngels Miralda: Has RIBOCA changed their stance since the publication of your co-authored article with Santa Hirsa? Have they responded to these publications other than the open letter?

Maija Rudovska: RIBOCA has replied in the format of an open letter,9 which addresses the issues we (Santa and myself) have pointed out in our criticism only partially. There has been no other forms of communication, no public discussions or anything similar. We are not surprised that RIBOCA keeps this sort of communication. Since its first edition in 2018, RIBOCA has not engaged with its critics. It should be noted that many of the issues we raised have failed to be addressed.

Àngels Miralda: Why is there so little international attention on this issue?

Žanete Liekīte: That's an intriguing question. I am curious as to why international media outlets eagerly publish articles announcing the comeback of RIBOCA and the supposed expulsion of specific sources of funding, only to turn a blind eye when confronted by local artworkers seeking to unravel the intricacies of the situation.10 They cite a lack of resources for fact-checking as a reason not to address the topic at all. It's a discrepancy worth exploring further.

However, it's worth noting Maija's observation about the convenience RIBOCA find in using the name of “Riga” to present themselves as a local institution. I've been having these conversations with fellow artworkers in the US about “our biennial.” Yet I don't grow tired of repeatedly emphasising that it's not Riga's biennial, despite their attempts to make it seem that way. It's fascinating how perceptions swiftly shift when you delve into the ambiguities only known to the locals, the information you can only unearth by googling in Latvian. That's when the reaction towards the event takes a rapid turn. It's crucial to continue shedding light on these unaddressed issues that everyone seems reluctant to confront. Regrettably, it seems that only through the spectacle of a grand conflict can the world be compelled to truly engage with these important issues. Yet, I am quite convinced that the twisted tango between the present international media's apathy and artworld's overall tendency to jump on the bandwagon of conformities will align itself accordingly.

Àngels Miralda: What do you see as a possible solution for RIBOCA?

Maija Rudovska: Right now I call for a boycott of RIBOCA. This is a position that I have slowly formulated for myself, looking at how the biennial is dealing with the current situation, their communication and their position on various issues, especially those that are related to the war in Ukraine. For a while I was silently hoping that RIBOCA would change its board, that it would do a kind of institutional cleansing from within, which, if done, could be a good basis for the biennial to continue existing in Riga, because it has already integrated itself in the local art ecosystem. However, I personally have been concerned from the very beginning about the colonialist rhetoric, the ignorance, the inability to communicate with the different social groups in the local art realm, especially the strategy of playing victims and blaming their critics of russophobia.

So what exactly has changed? Why couldn't RIBOCA take place last year and can this year? The war in Ukraine is not over. The biennial does not answer this question. In my opinion, if the artworld is serious about decolonisation, it is important to implement the difficult steps of this discourse instead of just theorising about it. Especially in Latvia, which has survived a long and complicated colonial history, we should take a position that is radical and without compromises.

End.