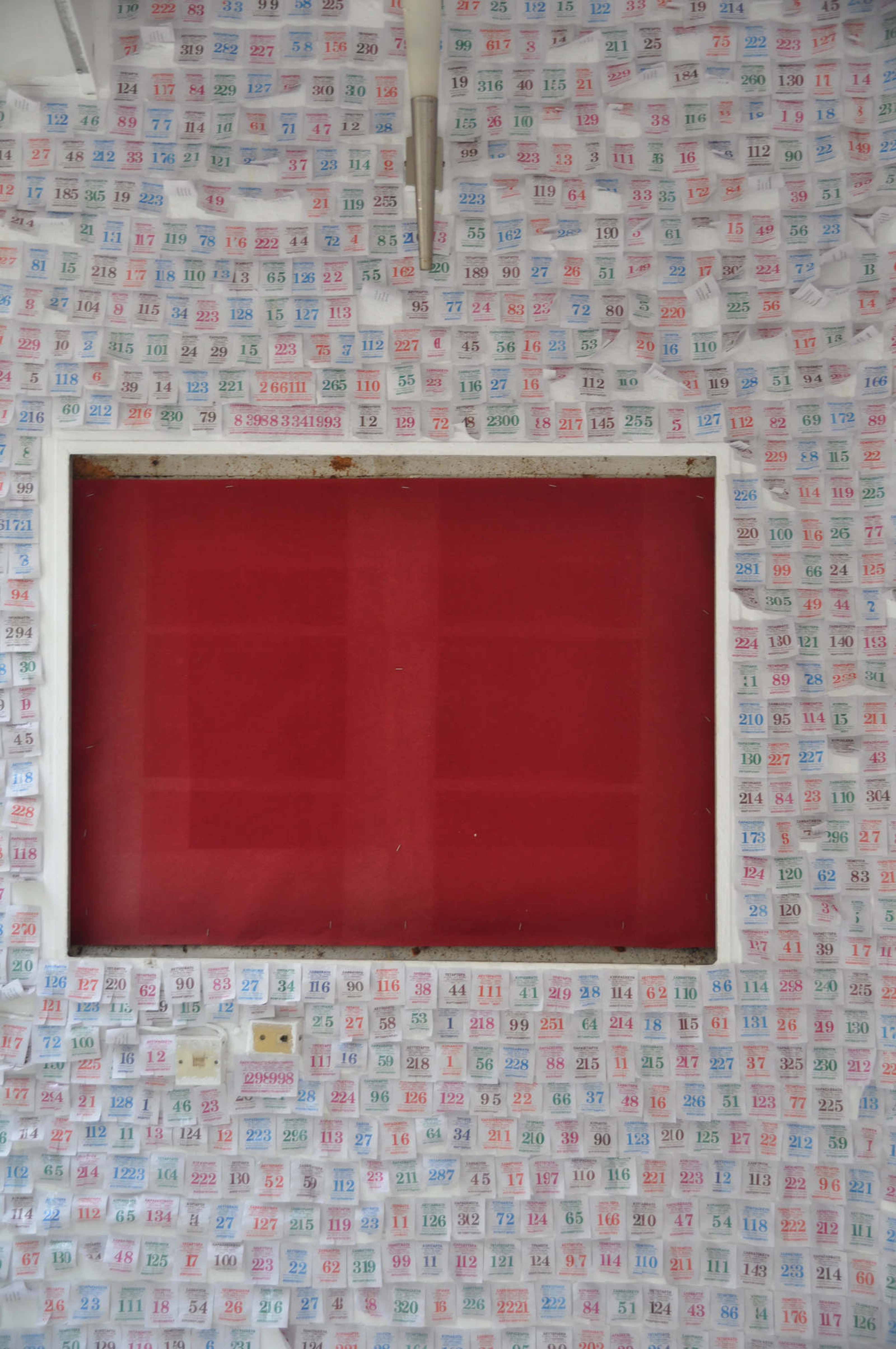

Kerenidis Pepe Collection: In your work “,” time—in the form of the calendar—is dissected, only to be reconstructed again as a superposition of temporalities. This bending of time also offers an alternative to the hierarchization of people into the privileged ones who have time for action, for leisure, for creation, for agency and those for whom things just happen one after the other, in a precarious way, trying to stay afloat. What is your relationship with time, as a Greek artist of a generation for which the socioeconomic crisis has become the new normal?

: What if a month consisted of 214 days and January merged with May? What if a week started on Thursday and ended on Tuesday? How many hours would one work per day, for how many hours would they relax or for how long would they sleep in this case? Who would hierarchize it and who would guide the program? In this work, I propose the end of regular times; a simple gesture of cutting and stitching calendar pages together, merging months, extending the days of a month and even reconsidering the seasons.

Days and months have names; they are defined by these. Different cultures and traditions apply different names. In some cases, the etymology of that name is temporal, in others, it refers to a yearly praxis or describes a condition or even, in the case of July and August, recalls emperors. These names cast a meaning and, finally, a rhythm. Meanings are not timeless. They shift from one point to another while cultures create systems that organize people’s everyday lives. A revolt or intervention of God appears sometimes crucial to describe what the free day would be, for example. In our time, there is one major category: Hours, Days, Months of work and of leisure.

Well, I am messing with that; I separate the syllables of a day, a month and reconnect them, play with them. I do not want to propose new names, I just want to deconstruct the old ones. I change the names in order to reimagine time conventions and, furthermore, to reimagine how everyday life would be structured without these limitations. Cultural limitations of the meanings stacked upon each other and carried by these words. Naming something in a different way may give it a new potential and the ability to reconsider rules and norms. I believe that language has the power to change structures.

Image: Chrysanthi Koumianaki – A Ten Day Holiday Is Not Enough To Save The World, 2015. Installation view at Sterna Residency

Chrysanthi Koumianaki – One Swallow Doesn’t Make a Summer, 2015. Installation view at Fireworks out of Season

Looking at this work again after 5 years, I find myself highly interested in the way that it was created. Its own temporality, the production time, the focus and the attention that was given to it during this collage process. To stick all these calendars, I was meeting, for some time, a close friend repeatedly in the evenings. She was coming to my place right after work for a couple of hours every day. We were cutting and stitching calendar pages in order to reach an amount of 3,500 new pieces that would cover a wall in an exhibition, but at the same time we were chit-chatting. Thinking about this, I gradually began to ask myself: was it, at the end, a certain task that required an amount of working hours to be completed or was it an opportunity to catch up with my friend? When we discussed this after some time, she also felt that it was a sharing between two people rather than a job that had to be done.

Do you believe that your collecting practice has similar qualities? Both of you work in different fields, you have different day jobs, timetables. Is it during your leisure time when you meet and exchange ideas and concerns? Is the collection a cut and stitch of different parts of your routines, your thoughts, your likes and dislikes, your beliefs as individuals? Is it a cut and stitch process that involves the artists you collect as well? Could you think of it as such in order to understand the new meanings that are created through your collecting process as a duet? Being part of the Phenomenon gatherings in Anafi, I always felt you had a big interest in creating non-linear dialogues by bringing people together. What exactly are the dynamics of this temporary Phenomenon community that you seek to create?

KP: We do see the collection as a shared activity, between the two of us, the artists of the collection, and the public. When we talk about collecting, we try to include more than just a private passion for acquiring works. It is also about understanding the ethics of collecting today, acknowledging the privileged position of a collector, pushing the limits of the market-driven art world by creating unexpected situations, like during our project on the Aegean island of Anafi, where time flows at a different pace allowing for dialogues, shared experiences, stories, and indeed the creation of a community. This is one of art’s forces, opening up discursive spaces and reclaiming time for affective encounters and political agency. Isn’t this also one of the reasons why you have founded 3 137, an artist-run space in Athens? Situating art creation within a socially engaged practice? And how have you found the interaction with similar artist-run initiatives in Athens or with the large private institutions that somehow are both trying to compensate for the state’s absence?

A band called Phaistos or Nestor or Mycenae, 2017.

Installation view at Phenomenon 2 organized by Kerenidis Pepe Collection in Anafi

CK: 3 137 was founded in 2012 by the artists Kosmas Nikolaou, Paky Vlassopoulou and I; the three of us have been friends since our college years in the fine arts school. Right before 3 137 came to exist, the idea was just to share a studio space. It felt like more than that, though, after only a couple of weeks. Being within a precarious everyday condition and a fragile—yet stubborn—cultural environment in Athens, and in Greece in general, we realized a common desire to become extroverted in our individual practices. Actually, we wanted to bring our private practices to the public through our studio space out of a need to emphatically realize that co-existence with other people—and not necessary art professionals—within the same city. It all started at the neighborhood scale and in a most unconditional way. 3 137 opened without considering viability in economic terms and was fully supported by the three of us; we just wanted the space to happen.

Up until 2015, there were no more than five non-profit spaces in Athens and there was a strong solidarity among us. To our surprise, things moved really quickly and the art scene has very much changed throughout the past few years. It is worth mentioning that more than 60 independent project spaces now operate in Athens, while independent artists’ happenings and shows appear all over Greece in a most contemporary way. It is too soon to jump to a solid conclusion as to why this has happened, though. We cannot be sure, for example, how and to what degree institutions like the Athens Biennale, or recently Documenta, that came to Athens from Kassel, had a share in that change along with funding programs from new private cultural institutions and, lately, new state programs that support artists. Do all these initiatives form a dynamic or a strange network of relationships? For me, it is both. I guess the existence of 3 137 in this network is the answer to your question. The sustainability of the space is still not secured though and we want more things to be reconsidered and even be reinvented.

On that ground, how do you find and position yourselves as collectors living in France but at the same time running a project in Greece in this period as well?

image: Chrysanthi Koumianaki – Notes for someone who is 167cm and wants to observe and concentrate, 2019. Installation view at Kunstraum am Schauplatz

Chrysanthi Koumianaki – Chroachym, 2016. Installation view at MENTIS, Center for the Preservation of Traditional Textile Techniques, Benaki Museum

KP: It’s one of the most insistent questions we have to deal with. How do we avoid parachuting ourselves in Greece and even more, on the remote island of Anafi, and what are the effects that this has on the island’s cultural policy? We approach this question by trying to create a situated project in alliance with the locals, researching past and present histories of the island, collaborating with academics and with the Greek art scene, all while acknowledging our specific position. We really believe that legitimacy springs from one’s actions and it has to be substantiated at every moment; it should not be pre-assigned based on the fact that we come from Greece and Italy, or that we are collectors living in France. And every time we think we are well positioned, we try to start reorienting, finding escape routes and questioning again and again. Our idea about the project is neither about teaching nor about learning, it’s simply about sharing a certain time in a certain space. And this brings us to our last question that has to do with the (de)construction of the social body, something which is quite central in your recent work; a body that shares the public space and whose gestures and actions are informed by social constructs, like the pavements, public transport, street signs. How can the body—often a dispossessed body—go beyond what it is supposed to be doing, how does what we “do”** do affect what we “can”** do?

CK: For the past few years, I have been thinking of the cityscape as a theatrical play setting while, at the same time, I found myself revolving around quite a famous phrase inversion, I must admit: “function follows form.” This stands for me as a constant question that shakes things—and not as an aphorism. I believe that we are actors; we act, but at the same time we carry and perform meanings and establish dynamic relationships by being within these relationships.

The materiality of the city in my works appears to be standing still for a glimpse. The city itself calls for observation and caring; it is a ground to rehearse on as well as a means to interpret it. It is a ground constructed of performed individual stories; a growing affection between the physical space organized as a city-system and the performer.

In recent works, for example, I reconstruct both the deformed urban equipment and the passer-by inhabitant as a new story to tell. It is like the stick and stitch process followed for the calendar I created. I am not trying to form new fragments of the urban space, but rather play with them: a bent sidewalk barrier tube, by the time it is deformed, can be the result of a strange dance gesture performed in the everyday city. At the same time, someone holding the handle on the bus patiently after a long day at work may generate the form of that tube just by recording the body’s position in abstract forms. This shape then can become a tattoo and form a new language of signs from scratch.

So, what we “do” do, as you said, just affects what we “can” do as individuals. I couldn’t agree more!

End.

This interview is part of a series of special features for the exhibition ‘1-31’ curated by Adam Carr.