In 1917, the Balfour Declaration prescribed Palestine as the ‘Jewish National Home,’ and with it came the rapid increase of Jewish immigrants to Palestine. By 1920, the British Mandate for Palestine was granted at the San Remo Conference, and in 1922 it was formally adopted by the League of Nations—despite heavy opposition by the Palestinian Arabs. Settlers began to push Palestinians out of their vibrant cities and into slums. These rapidly changing conditions spurred the Palestinian Muslim and Christian populations to organize large demonstrations against preferential treatment for Jewish settlers under British rule. The 1920s also saw the establishment of armed extremist Jewish forces such as the Haganah—an illegal paramilitary group that later became the core of the Israeli Defence Forces during the Nakba. These political pressures culminated in the Great Arab Revolt of 1936—a period of intense violence that continued for years and saw mass displacement, thousands of homes demolished, and collective punishment.

Towards the end of the British Mandate, World War II broke out in Europe. During this period, Zionist paramilitary groups continued to emerge, notably the Irgun and Palmach, which posed a significant threat to British control. Zionist violence wreaked havoc on both the British military and Palestinians and began to steer Britain towards speeding up its departure. In the aftermath of WWII, Britain handed the “question of Palestine” to the UN. A Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) was established to find a solution; the outcome of which was The Partition Plan of Palestine. The Arab Higher Commission was not taken into consideration when the plan was signed in 1947 and Palestine was divided into three: a Jewish state, an Arab state, and Jerusalem, placed under a Special International Regime.

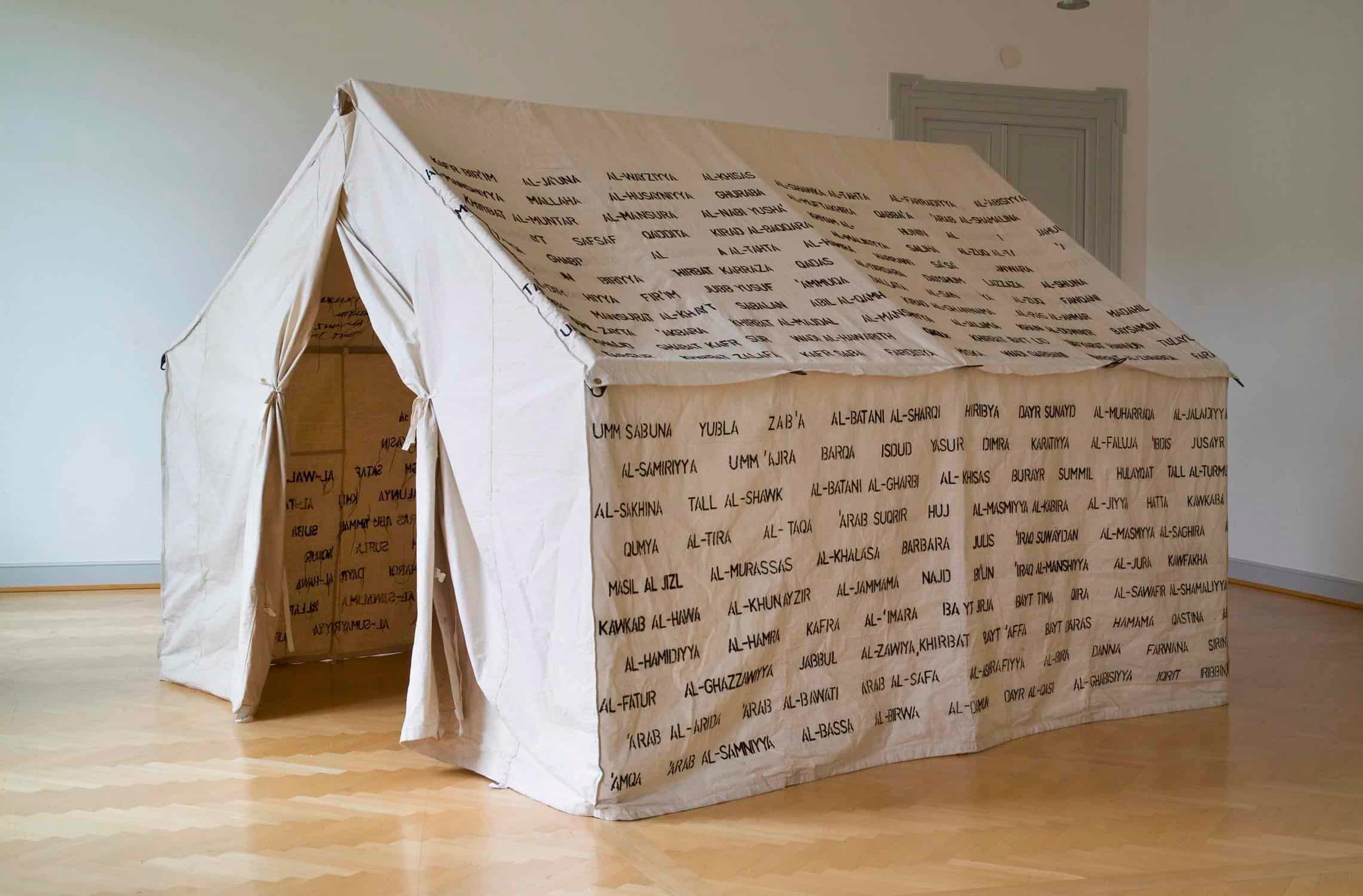

Palestinians lived all over Palestine and not exclusively in the areas designated as Palestine by the United Nations. The reckless ethnic divisions and borders awarded to the Zionists foregrounded the Nakba. The "catastrophe" witnessed the forced displacement of Palestinians from over 500 villages by the settler Zionist movement; exiling half of the population, erasing industries, and extinguishing vital social and cultural traditions; thereby creating a never-ending trauma for a people,1 inflicting double damage on both the land of Palestine and its indigenous people, Palestinians.

Emily Jacir \ Lydda Airport film still, 2009. Installation with single channel film and sculpture. Courtesy of the artist. © Emily Jacir 2009

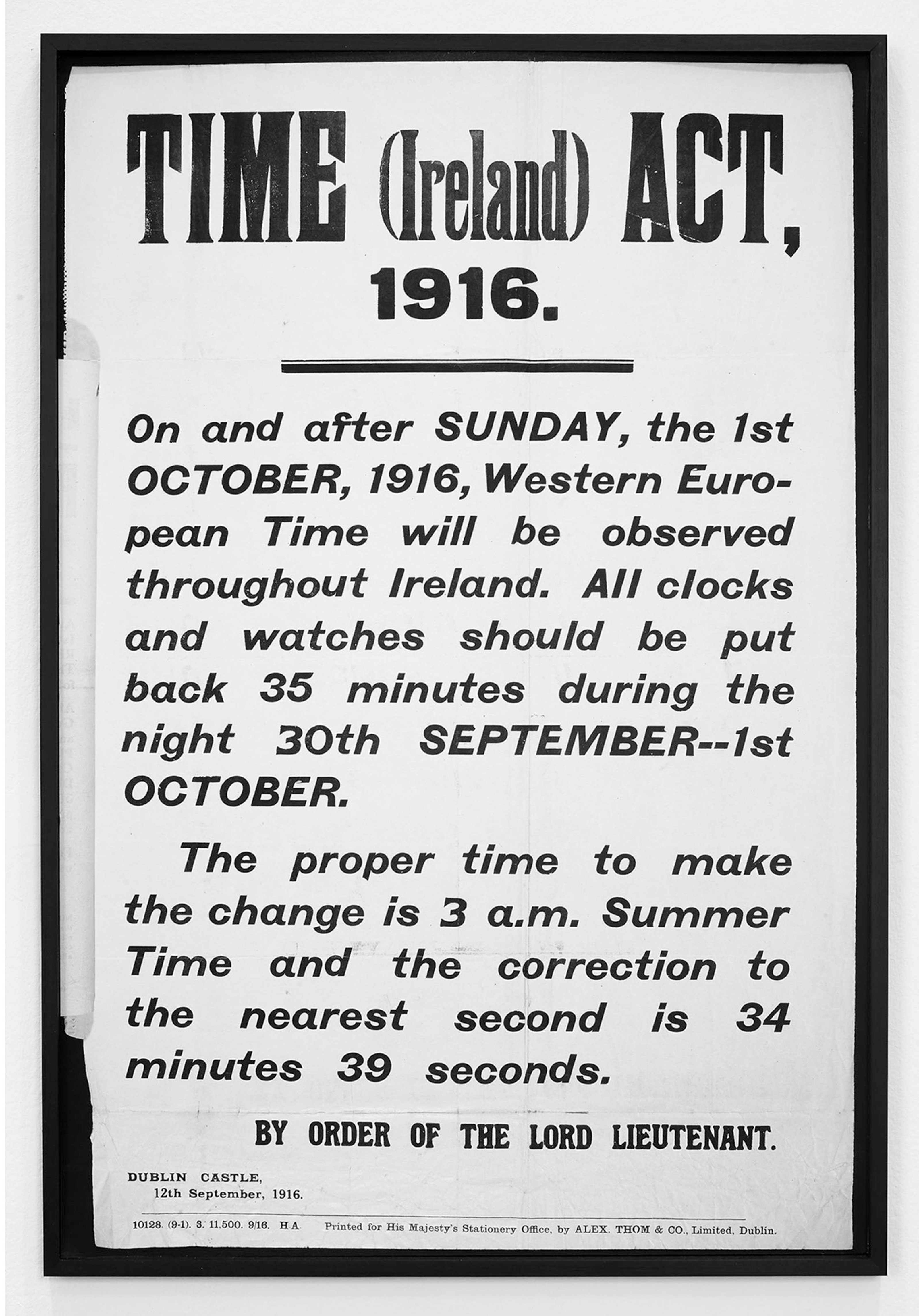

The centerpiece of Emily Jacir’s Notes for a Cannon (2016), created for the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in Dublin, is a site-specific sound work in the Royal Hospital Kilmainham Clock Tower. Meanwhile, inside IMMA an array of images, documents, sculptures, videos, and objects results in an interconnected constellation of historical and social struggles in two distinct geographies for national liberation against British occupation. The anti-colonial struggles in Ireland and Palestine share a long history of solidarity and lived experiences that testify to the globalized brutality of the British army in its quest for military domination.

The piece expands into the streets of Dublin, where the colonial standardization of time finds a parallel in Palestine’s history. In 1922, British officials in Jerusalem demolished the Jaffa Clock Tower that told the time in both “European-style” standardized time and “Ottoman-style,” where high noon shifts with each day according to the temporality of the sun. The Jaffa Clock Tower was a testament to how two different perceptions of time can live side-by-side in harmony.

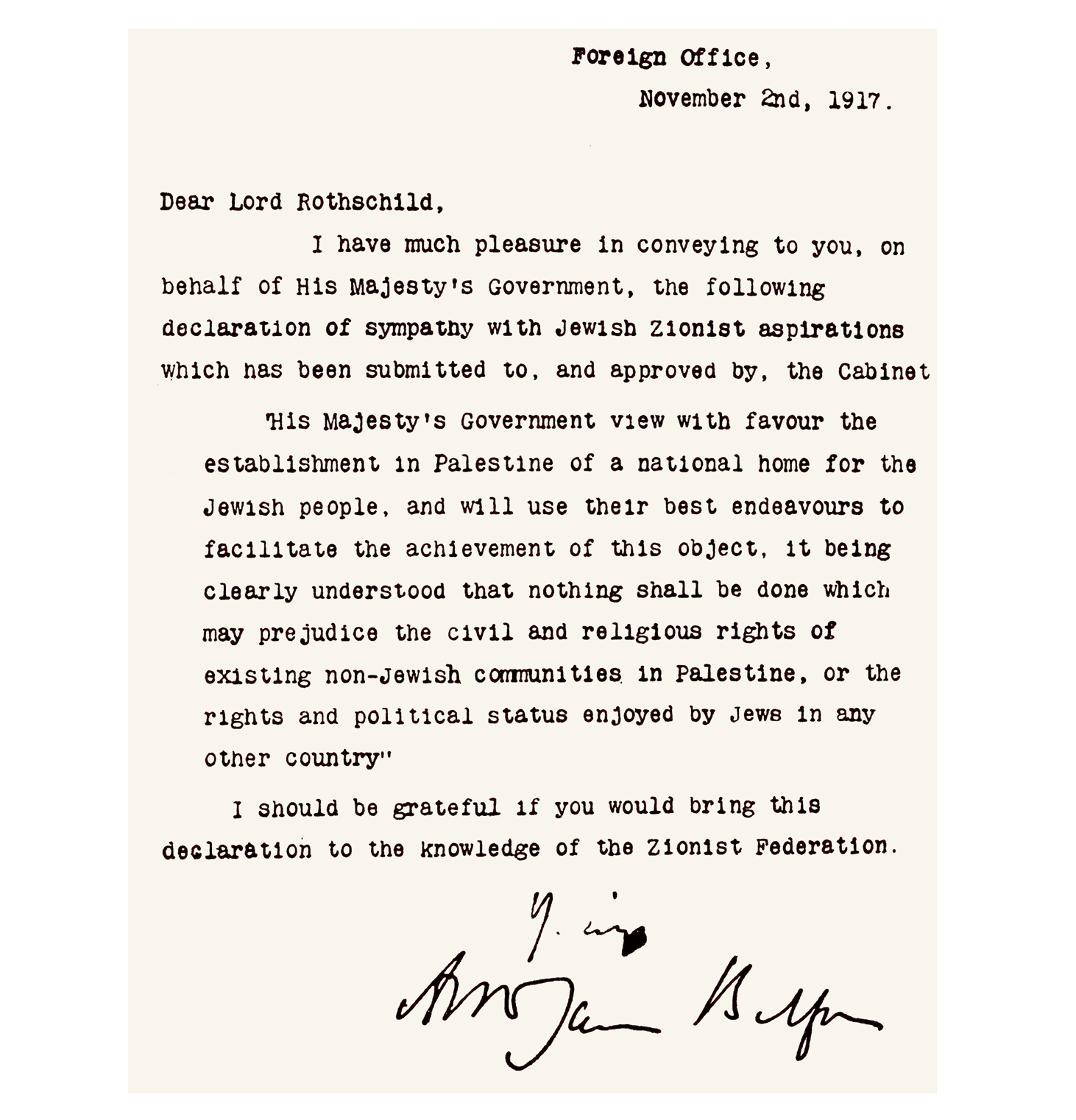

The Balfour Declaration, penned by British Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour in 1917, pledged British support for establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine. This commitment aligned with the goals set during the First Zionist Congress in 1897, aiming to secure a home for the Jewish people under international law. Its primary intent was to win extensive Jewish backing during World War I while serving Britain's strategic interests in controlling Egypt and the Suez Canal.

The British cabinet endorsed the declaration, which stated: "His Majesty's Government views with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object. It is clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

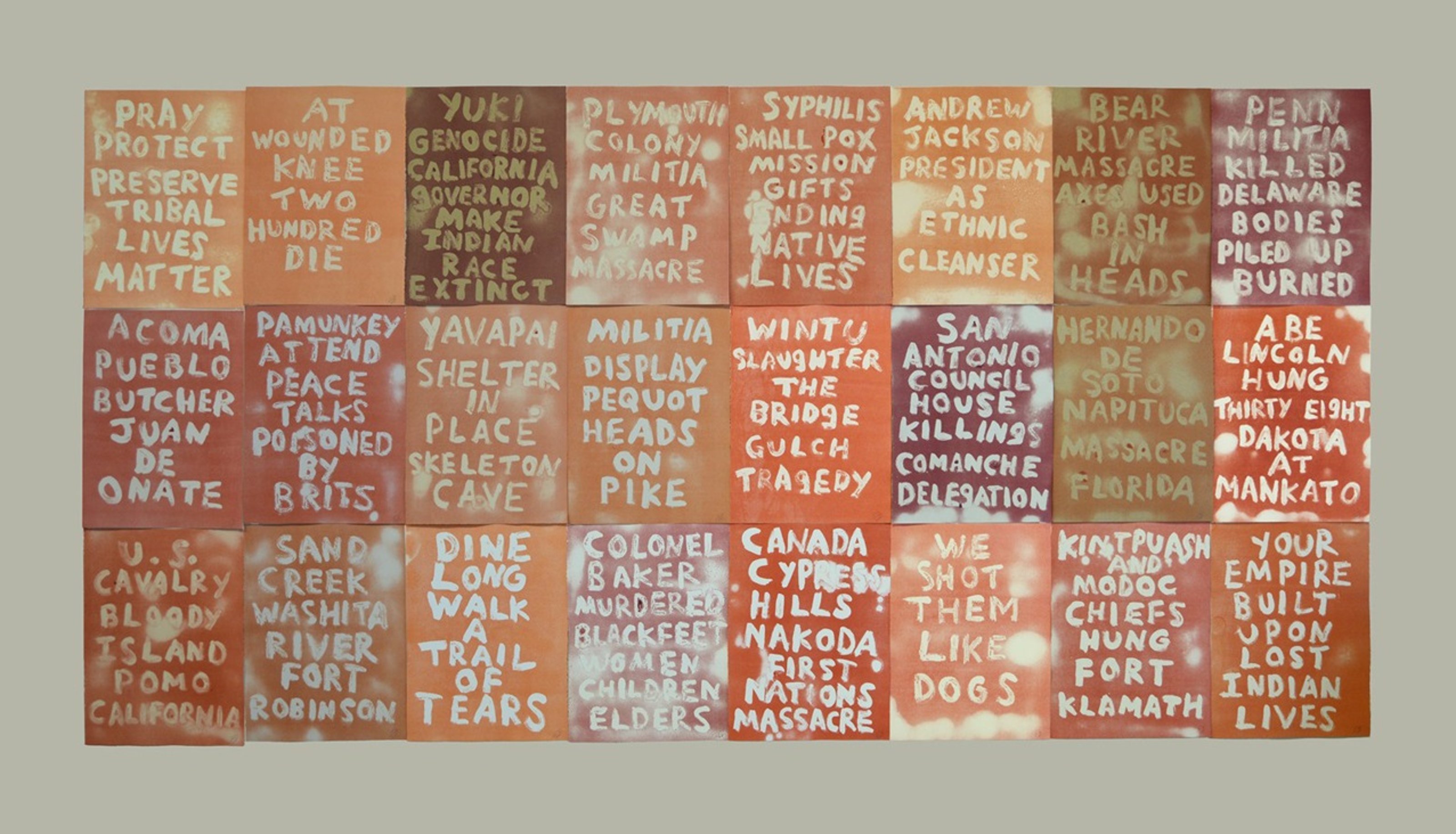

At that time, the Ottoman Empire controlled Palestine, where Arabs comprised 90% of the population and Jewish settlers made up the remaining 10%. The declaration recognized national rights for the Jewish minority but limited the Arab majority to civil and religious rights, referring to them as "non-Jewish communities."

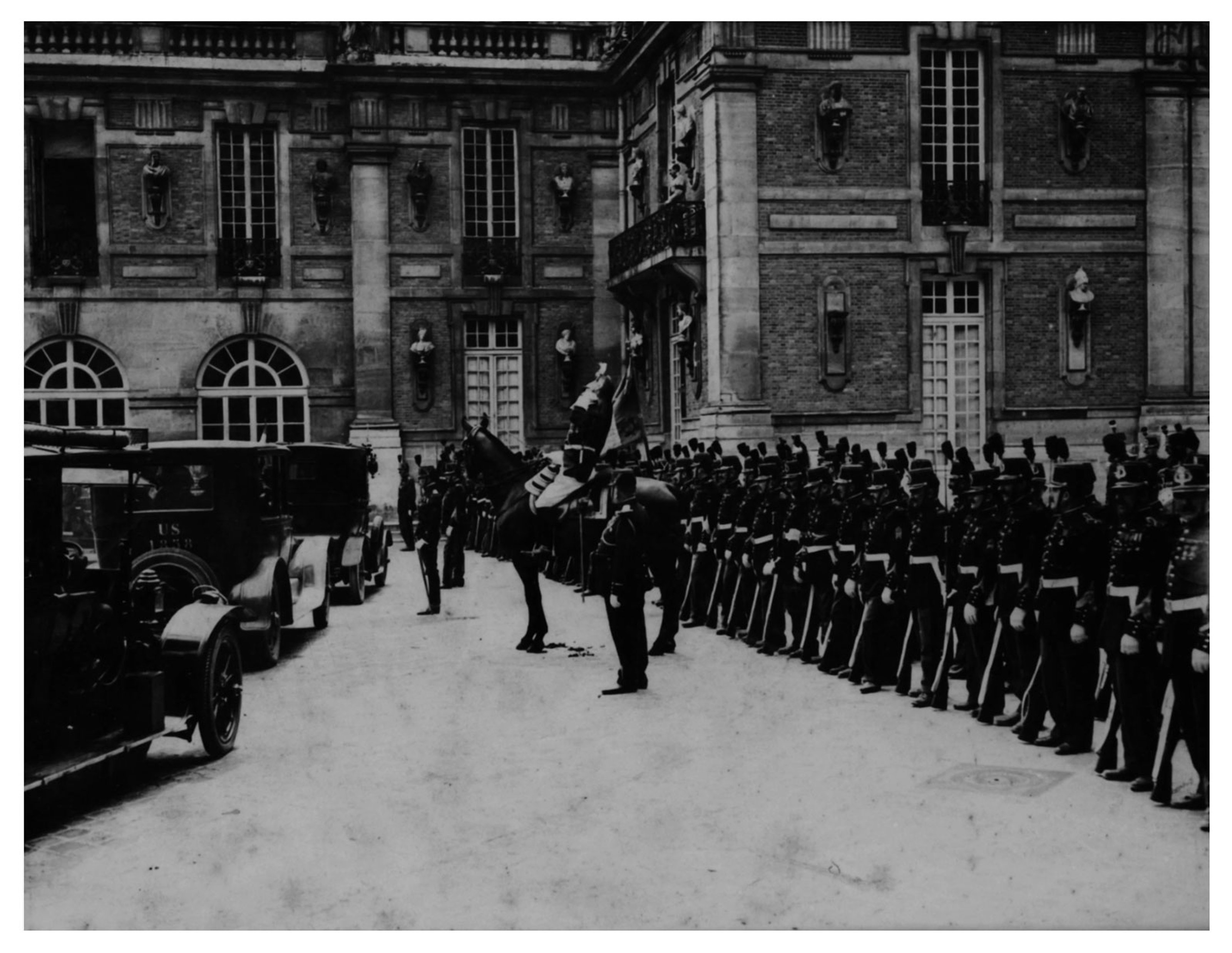

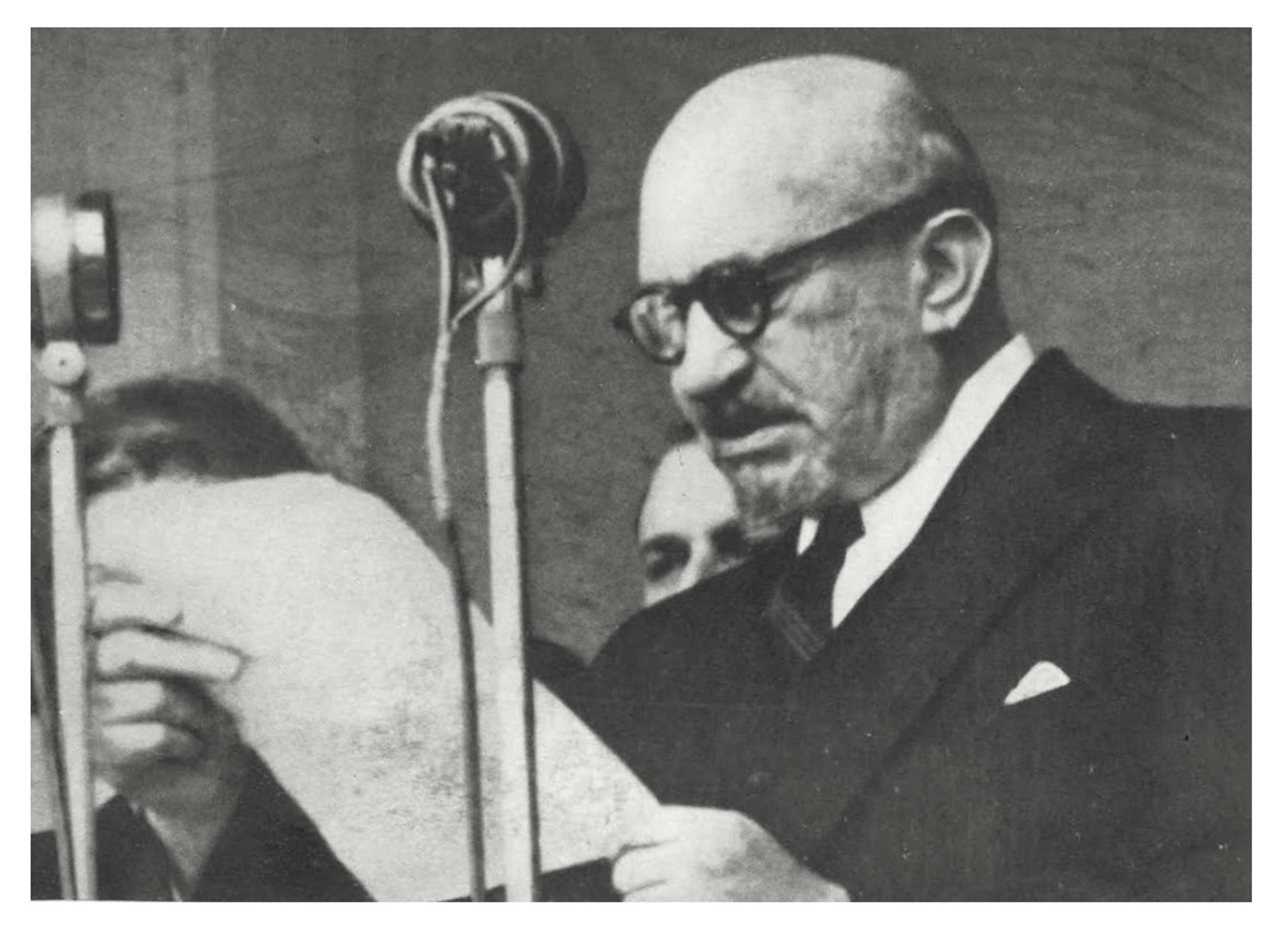

During the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Lord Balfour explicitly stated: "In Palestine, we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country… The Four Great Powers are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, is of far more profound import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land."

In this double podcast episode about the class struggle in Palestine during the British Mandate (1920-48), Working Class History discusses the organizations built by Palestinian workers, the 1936-39 revolt, and a number of joint strikes by Arabs and Jews which happened against the backdrop of rising tensions culminating in the ethnic cleansing of the Nakba. Part One. (Podcast)

Lord Balfour, Paris Peace Conference of 1919

Emily Jacir \ Notes for a Cannon (2016). Site specific sound piece at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham Clock Tower. Multimedia installation at IMMA which includes drawings, video, texts, photos, and archival material and objects.

On June 5, 1916, the Arab uprising, supported by the British, marked a pivotal challenge to the Ottoman Empire. By this time, anti-Turkish sentiments were widespread across Arabic-speaking regions such as Damascus, Cairo, Baghdad, and Jerusalem. Following a 1908 coup by the Young Turks, hopes for autonomy within the empire were dashed as they implemented strategies of centralization and Turkification of the Empire.

Amid these tensions, the Sultan declared a global jihad against British and French forces, primarily to thwart foreign influence in regions critical to the British, notably around the Suez Canal, essential for protecting British interests in India. In response, the British engaged in secret negotiations, crafting treaties with various factions to maintain their influence.

A key figure during this period was Sharif Hussein of Mecca, a Hashemite leader seeking to break free from Ottoman control. Viewing the British as vital allies for his cause, he communicated with Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt. The British, in turn, promised Hussein a vast independent Arab state encompassing Syria, Arabia, Iraq, and TransJordan, contingent on his support for the Arab revolt against Ottoman rule.

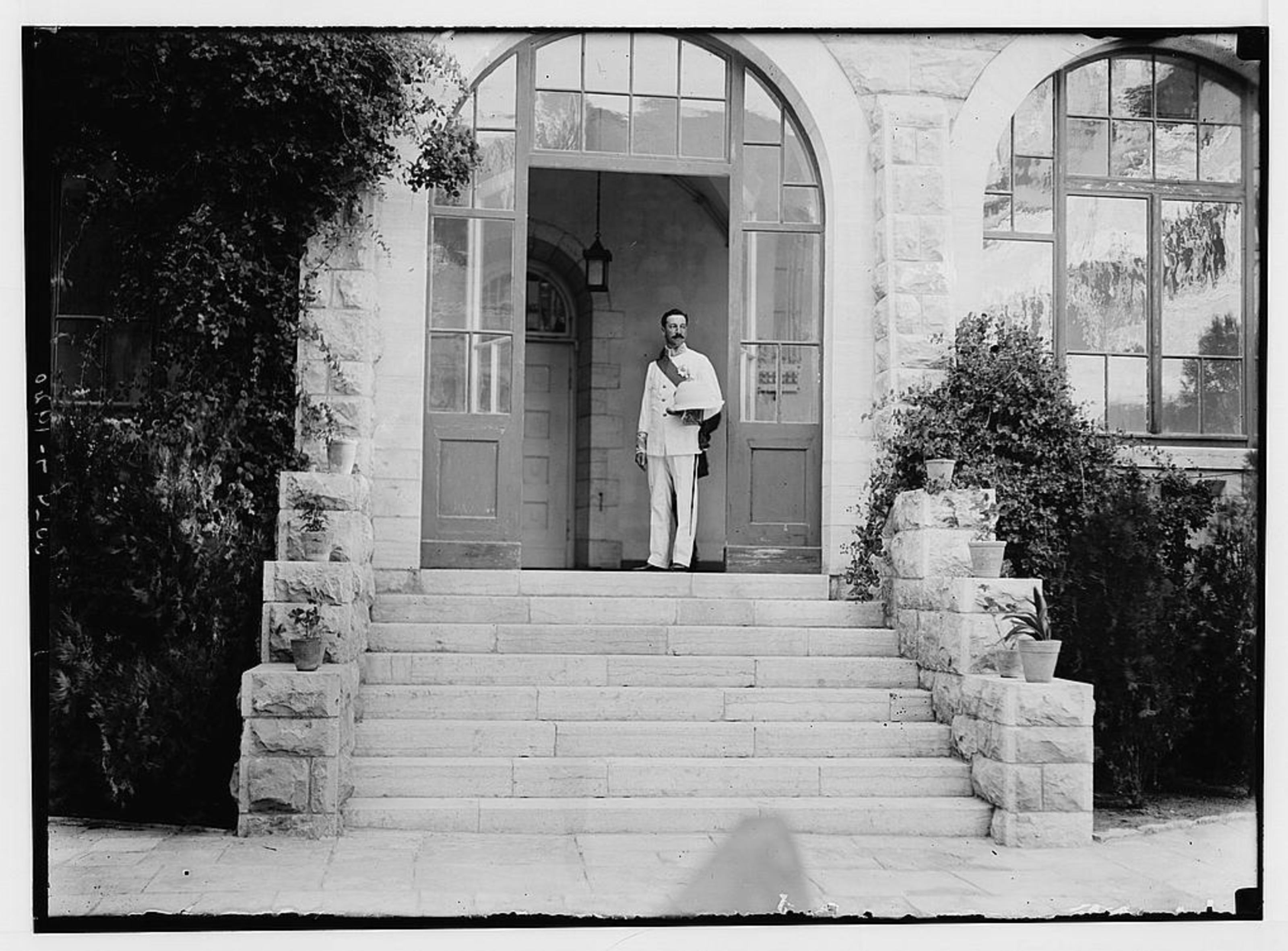

Sir Ronald Storrs

Governor of Jerusalem

Emily Jacir \ Notes for a Cannon (2016). Site specific sound piece at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham Clock Tower. Multimedia installation at IMMA which includes drawings, video, texts, photos, and archival material and objects.

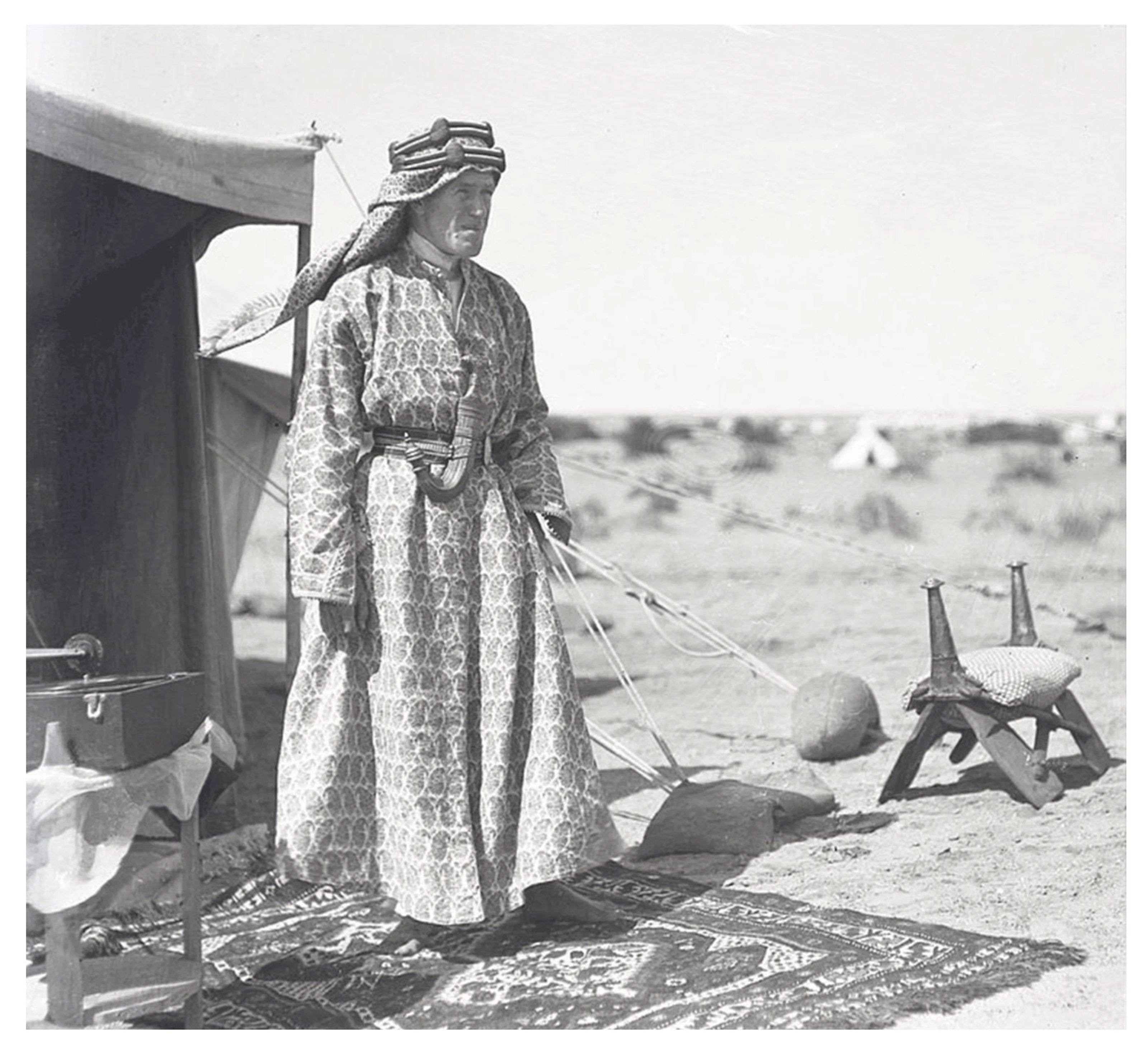

Thomas Edward Lawrence (T.E. Lawrence) was a British army intelligence officer, diplomat, and writer. He was fluent in Arabic and familiar with the culture and customs of the Arab world. This allowed him access to an influence in a region which the British army had a keen interest in controlling.

He worked as a British liaison officer with Arab nationalist forces fighting against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. He attached himself to the staff of King Faisal I - King of Iraq. Faisal proclaimed the independent Kingdom of Hejaz in 1916 with support promised by the British Army. The territory was a narrow stretch along the Red Sea on the side of the Arabian peninsula reaching to the borders of Jordan and Palestine. Faisal had agreed to fight the Ottomans alongside the British in exchange for the promise of an independent Arab state including Jordan, Iraq, most of Syria, and Palestine. T.E. Lawrence was instrumental in gaining the trust of Faisal for the British. He became known for his prominent successes in both the Arab Revolt (1916-1918) as well as the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915-1918) in which British, French, Italian, and Arab forces repelled the Ottoman army.

T.E. Lawrence is credited with instilling Arab nationalism into the region - an ideology which he assumed was not mutually exclusive with Zionism. He spoke to Arabs about reviving their greatness, and promoted nostalgia for the empires that once spread from Persia to Spain. He wove romantic imagery into the minds of people to sow discontent with foreign rulers knowing the power of these ideas and ideologies. Privately, he expressed different ideas about the greatness of the Arabs. As he described in his book “The Seven Pillars of Wisdom,” the Arabs were a “manufactured people” whose “name has been changing in sense year by year,” only united by “a language called Arabic.” This concept of Arab nationalism, he predicted, “would stick and drive the revolt forward,” as they were “incorrigible children of the idea” who “could be swung on an idea as on a cord.”

The discourse of “Arab nationalism” and “Arab independence,” which Lawrence had formulated himself, was apparently not taken into account by the British government since, both in accordance with the articles of the Paris Peace Conference and also as indicated earlier in the Sykes-Picot agreement, the Arab territories outside Lebanon, the coastal part of Syria, and Palestine had come under the British mandate. Lawrence fooled the people who gave him their confidence and esteem, once they finished fighting by his side, the promises he had made were swiftly broken and control of the region was granted to the British and French colonial mandates.

Emily Jacir \ Notes for a Cannon (2016). Site specific sound piece at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham Clock Tower. Multimedia installation at IMMA which includes drawings, video, texts, photos, and archival material and objects.

The British campaign against Ottoman-held Palestine during 1917–18 marked their third major military effort in the Middle East during World War I. The operation commenced in early 1917, featuring intensive combat and strategic advancements over a territory stretching 600 kilometers to the north, culminating from late October through December of that year.

This military push resulted in the capture of key regions, including the Jordan Valley, and subdued Ottoman forces, establishing British occupation in Palestine until 1920. Following the war, the League of Nations implemented the Mandate system to transition former Ottoman territories toward independence. Palestine was designated as a Class A Mandate under British governance, indicating it as a community provisionally recognized for eventual independence, requiring only administrative guidance and support. Meanwhile, Syria and Lebanon were placed under French control. Though Lebanon and Syria achieved independence by 1944, and Jordan by 1946, Palestine continued to experience prolonged conflict and did not follow a similar path to sovereignty.

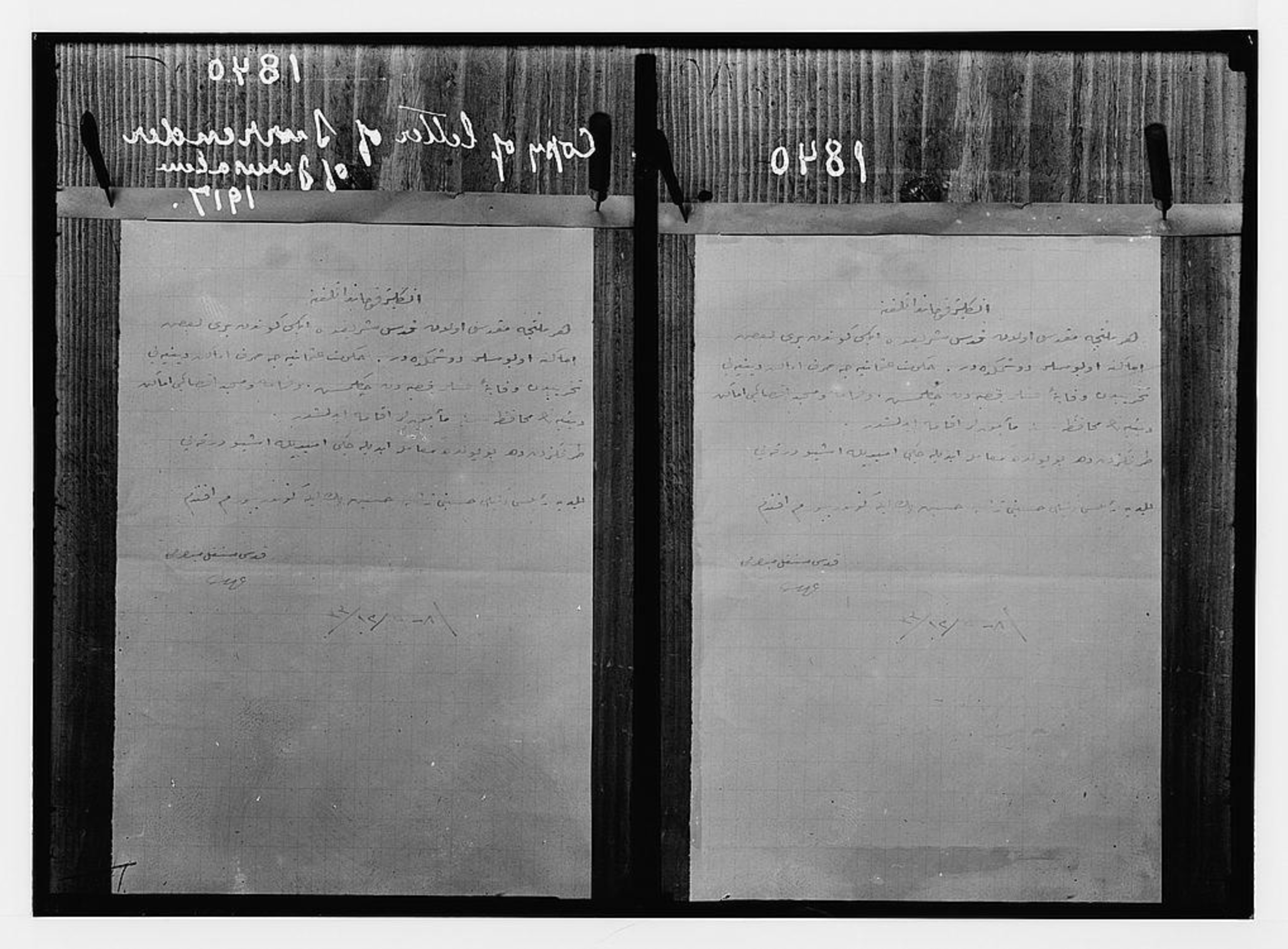

The surrender of Jerusalem to the British, December 9th, 1917. Copy of the letter of surrender. Matson Collection, Library of Congress.

The role that former “Black and Tans” played in Palestine during the years prior to 1948 has not been adequately studied. Their story does not begin there, but rather with the British actions in Ireland several years earlier. The “Black and Tans,” whose official name was the “Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary,” were auxiliary police that the British brought to Ireland to try to squelch the Irish Rebellion in 1919 and 1920. The Irish had grown more and more critical of British rule and by 1919 many Irish were openly resisting British control. Some forms of resistance included armed struggle. In an effort to shore up their slipping police and military control, Britain enlisted men into quasi counter-insurgent squads. They consisted mostly of young British veterans from World War I who subsequently received little if any training about how to “police” a civilian population. They were called “Black and Tans” because their uniforms consisted of black pants and tan shirts, apparently the result of making do from the remnants of various squads or brigades.

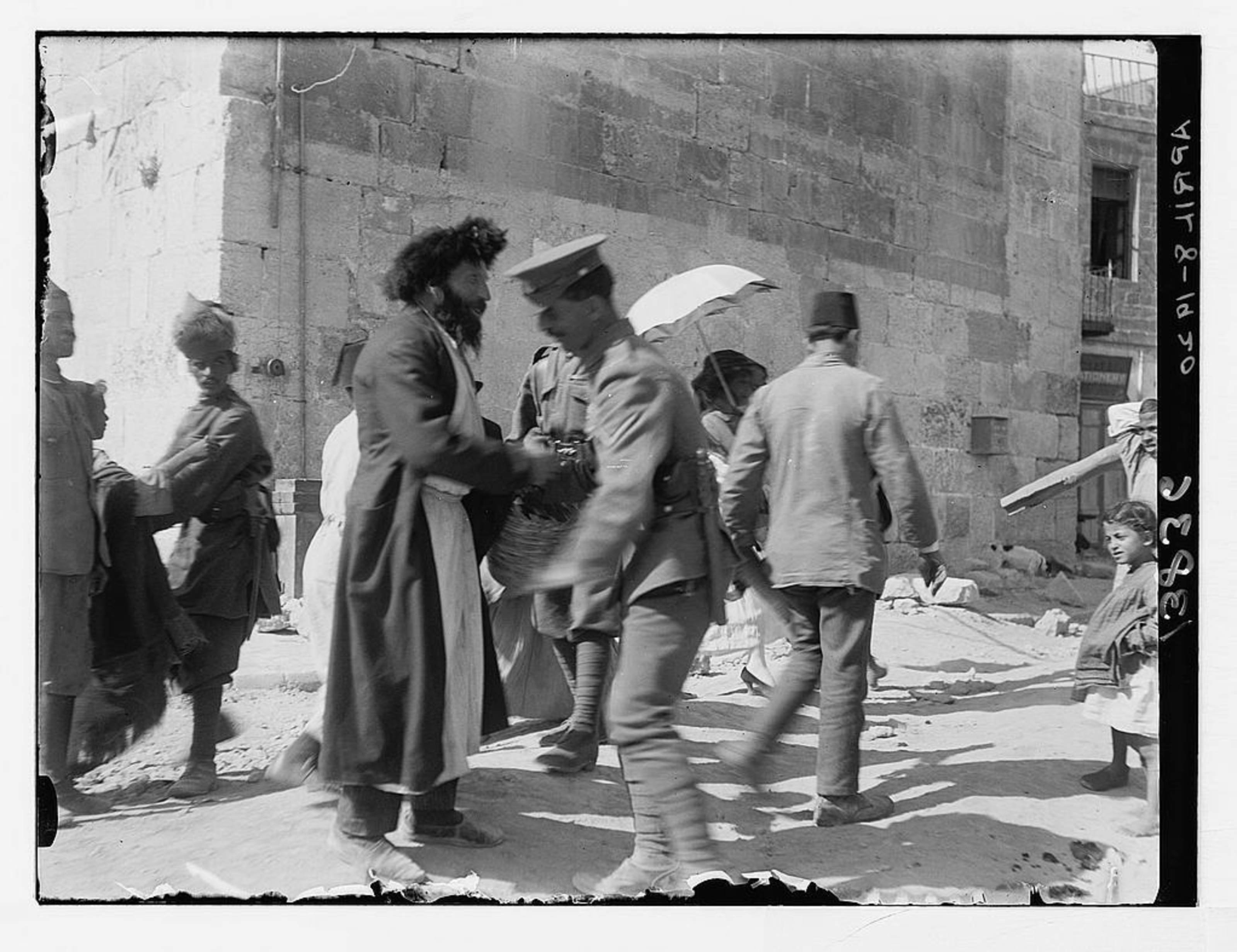

In 1918, Chaim Weizmann, who was the president of the British Zionist Federation, formed the ‘Zionist Commission.’ The commission was formed in the light of the newly issued Balfour Declaration, and its aim was to study conditions in Palestine and report back to the British. The commission made visits to Palestine and worked to establish a basis for cooperation with the British Military forces there, as well as focused on the steady development of Jewish Settlements in Palestine.

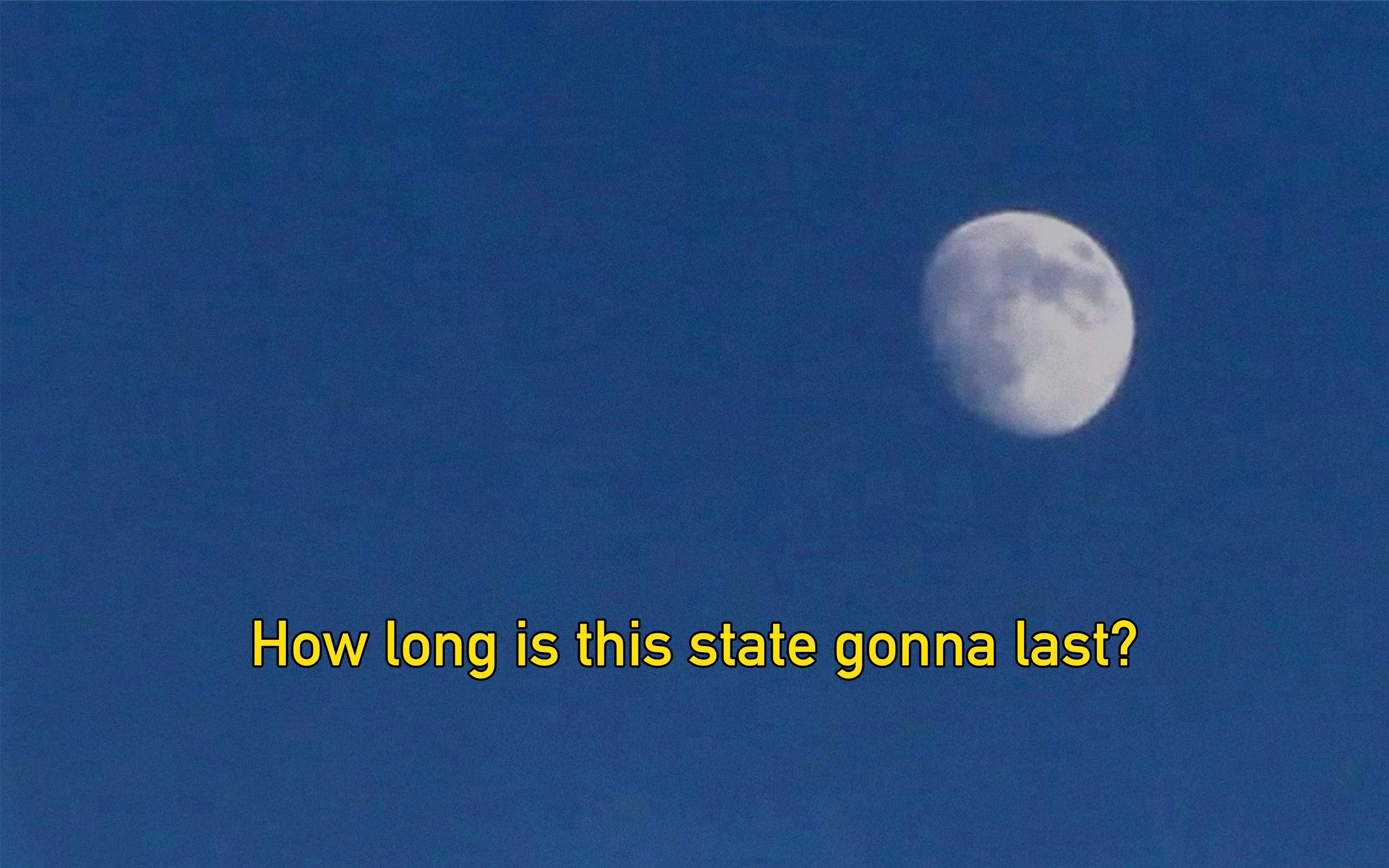

The films of Basma al-Sharif often contain landscapes, cityscapes, and social environments that map out the fractured psychogeography of the Palestinian diaspora. She represents her own experience, as a drifting subject between the Middle East, Europe, and the US, and the resulting understanding of a shattered world that taps into a relatable experience of wanderers. The films offer a visual description of the duality of distance that provides both safety and yearning. If diasporic identities become more complex and layered from various inputs and influences, they simultaneously become more defined by their singularity among otherness. Al-Sharif’s films layer memory through superimposed locations building vignettes of nonlinear time.

Basma al-Sharif \ Farther Than The Eye Can See, 2012 (Excerpt)

Basma al-Sharif \ Farther Than The Eye Can See, 2012 (Excerpt)

Signed on January 3, 1919, between Emir Faisal of the Arab Kingdom of Hejaz and Chaim Weizmann, the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement aimed to foster Arab-Jewish cooperation post-World War I. The agreement recognized Jewish aspirations for a homeland in Palestine as outlined in the Balfour Declaration and supported Arab independence across the broader region. Key terms included mutual recognition of national aspirations, economic cooperation, and cultural exchange. However, the agreement was signed under questionable circumstances. It was presented to Faisal by T. E. Lawrence. Faisal, who did not understand English, relied on an Arabic translation provided by Lawrence and signed the document without his advisors present, relying on translations that might not have fully conveyed the agreement's details.

Furthermore, the Zionists submitted the agreement to the Paris Peace Conference without including Faisal's crucial conditional clause that made the agreement contingent on the Arabs gaining their anticipated independence. This omission significantly altered the perceived commitments and understanding between the parties. The absence of Faisal's condition, combined with the language barriers and lack of advisory support during the signing, underscores deceptive tactics used in the negotiations. These complexities and the rapidly shifting political landscape following World War I contributed to the eventual failure of the agreement as tensions between Jewish and Arab communities escalated under the British Mandate for Palestine.

The Paris Peace Conference (1919–20), was a meeting of the victorious allies of WWI that inaugurated the international resettlement and decided the future of people living in the territories of the defeated states. The conference ultimately decided that conquered Arab provinces would not be restored to Ottoman rule.

On President Wilson’s insistence, a commission was appointed to determine the wishes of the indigenous populations in the Ottoman territories of Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and Anatolia. Henry C. King and Charles R. Crane, US members of the International Commission of Inquiry, proceeded alone after Britain and France refused to join the commission.

The King-Crane Commission of Inquiry recommended an American Mandate over Syria, including Palestine. In assessing the wishes of the indigenous population of Palestine, the commission called for “serious modification of the extreme Zionist program for Palestine of unlimited immigration of Jews.” The commission declared that this program, aiming “finally to make Palestine distinctly a Jewish State [would be] a serious injustice” and it “should be given up.” Dealing with the Zionist claim “that they have a ‘right’ to Palestine, based on their occupation of two thousand years,” the commission remarked that this claim “can hardly be seriously considered.” The report cautioned: "Not only you as president but the American people as a whole should realize that if the American government decided to support the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, they are committing the American people to the use of force in that area, since only by force can a Jewish state in Palestine be established or maintained."

However, the outcome of the Paris Peace Conference was largely undermined from the beginning as it had already been predetermined by the Sykes-Picot agreement between Britain and France on how the Ottoman Empire would be carved up.

Basma al-Sharif \ Farther Than The Eye Can See, 2012 (Excerpt)

In June 1920, the formation of the Haganah (Defence) was announced. An extension of Hashomer (the Guardian)—founded in 1909 with the slogan “Judea was lost by blood and fire and will raise again by blood and fire,” and the first paramilitary organization to assume security functions for the settlements in the Galilee—the Haganah declared itself a secret military formation with the object of protecting the Jewish community in Palestine in 1924.

The Haganah’s activities were quite expansive. Linked to the Jewish Labor Unions, the Haganah trained members in firearm use in Zionist Kibbutzim, with some later joining the British police. The paramilitary acquired weapons through deals and smuggling from outside of Palestine, as well as manufacturing in small workshops. During World War II, hundreds of Haganah members joined the British army, gaining military experience and hoarding weapons.

Disturbances erupt in Jerusalem amid fears of Zionism and disillusionment over unmet promises of independence, resulting in the deaths of 5 Jews and injuries to 200 others. In response, the British established the Palin Commission of Inquiry to investigate the riots. Despite lacking Palestinian consent, the Supreme Council of the San Remo Peace Conference assigns the Palestine Mandate to Britain. Subsequently, British authorities obstruct the convening of the Second Palestinian National Congress. Meanwhile, the First Immigration Ordinance imposes a quota of 16,500 Jewish immigrants for the initial year. Following these developments, the Third Palestinian National Congress elects an Executive Committee, which retains control of the Palestinian political movement from 1920 to 1935.

Herbert Samuel, a British politician and diplomat, played a pivotal role in the events surrounding the British Mandate for Palestine. Samuel, who was Jewish himself, was appointed as the first High Commissioner for Palestine in 1920, a controversial appointment that was deemed “illegal” by the military government, headed by Edmund Allenby, as a formal peace treaty with the Ottomans had not been signed; this violated both military law and the Hague Convention. Samuel’s position gave him significant influence over the administration of the territory.

As High Commissioner, Samuel implemented policies that favored the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine, as outlined in the Balfour Declaration. His appointment represented a departure from previous British policies in the region, which had been more neutral or even pro-Arab.

Under Samuel, the British Mandate for Palestine was ratified at the League of Nations in 1922, despite objections from indigenous Palestinians. The mandate, heavily influenced by Samuel and other proponents of Zionism, laid the groundwork for the influx of Jewish immigrants into Palestine and the establishment of Jewish settlements, while marginalizing the rights and aspirations of the Palestinian population.

Samuel's tenure was marked by tensions between Jewish and Arab communities in Palestine, as well as criticisms from both sides regarding his handling of the mandate. His support for Zionist objectives often came at the expense of Palestinian rights and self-determination, further exacerbating tensions and laying the groundwork for future conflicts in the region.

Sir Herbert Samuel, H.B.M. high commissioner, etc. Lord Allenby, Sir Herbert Samuel and Emir Abdullah, 1920-1925. Matson Collection, Library of Congress.

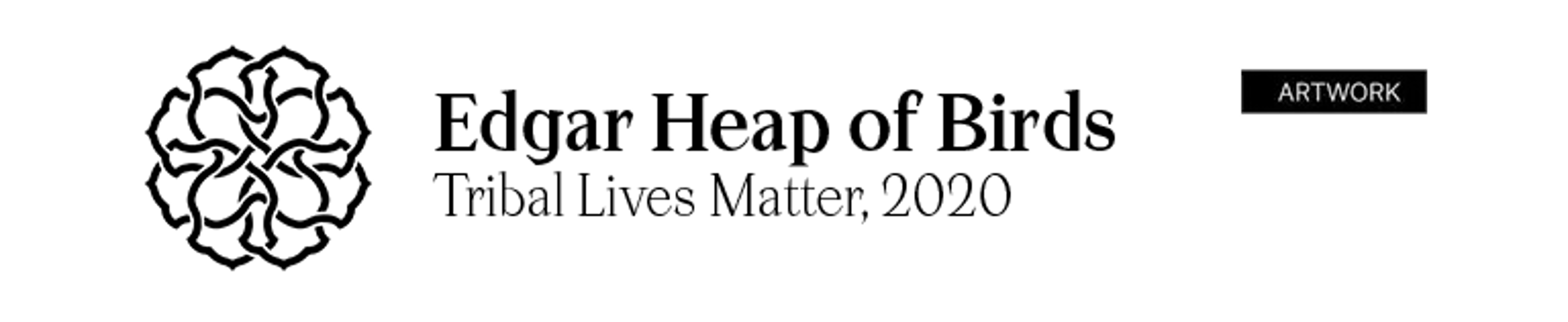

The decolonial struggles of Indigenous people around the world are interconnected by their shared histories of oppression, land dispossession, and cultural erasure. Palestine represents one of the ongoing decolonization conflicts, rooted in a prolonged struggle against occupation and displacement. The shared experience of fighting for the right to exist on ancestral lands, preserve cultural heritage, and attain political autonomy fosters profound solidarity among Indigenous and other oppressed groups, uniting them in a common narrative of resistance and resilience against colonial legacies.

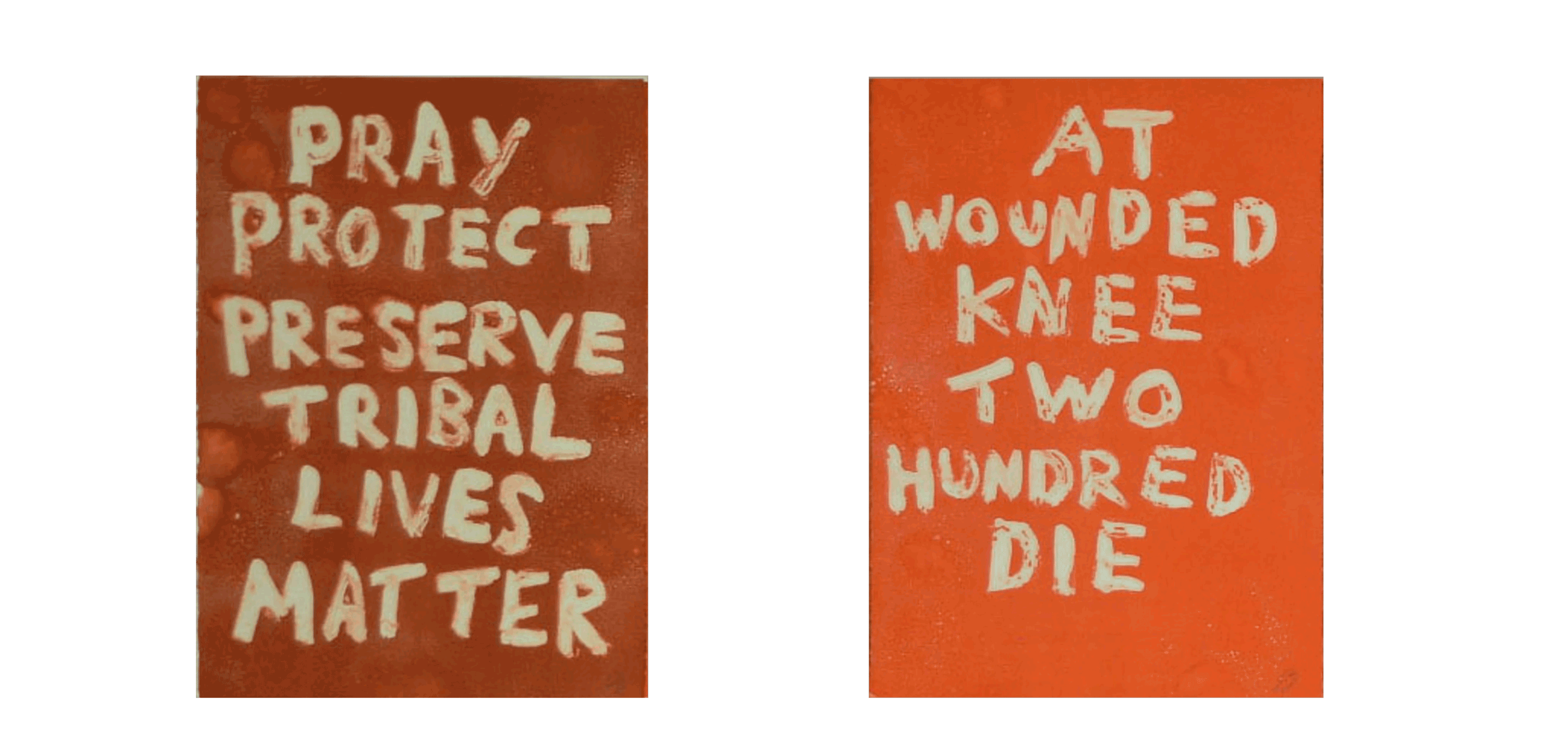

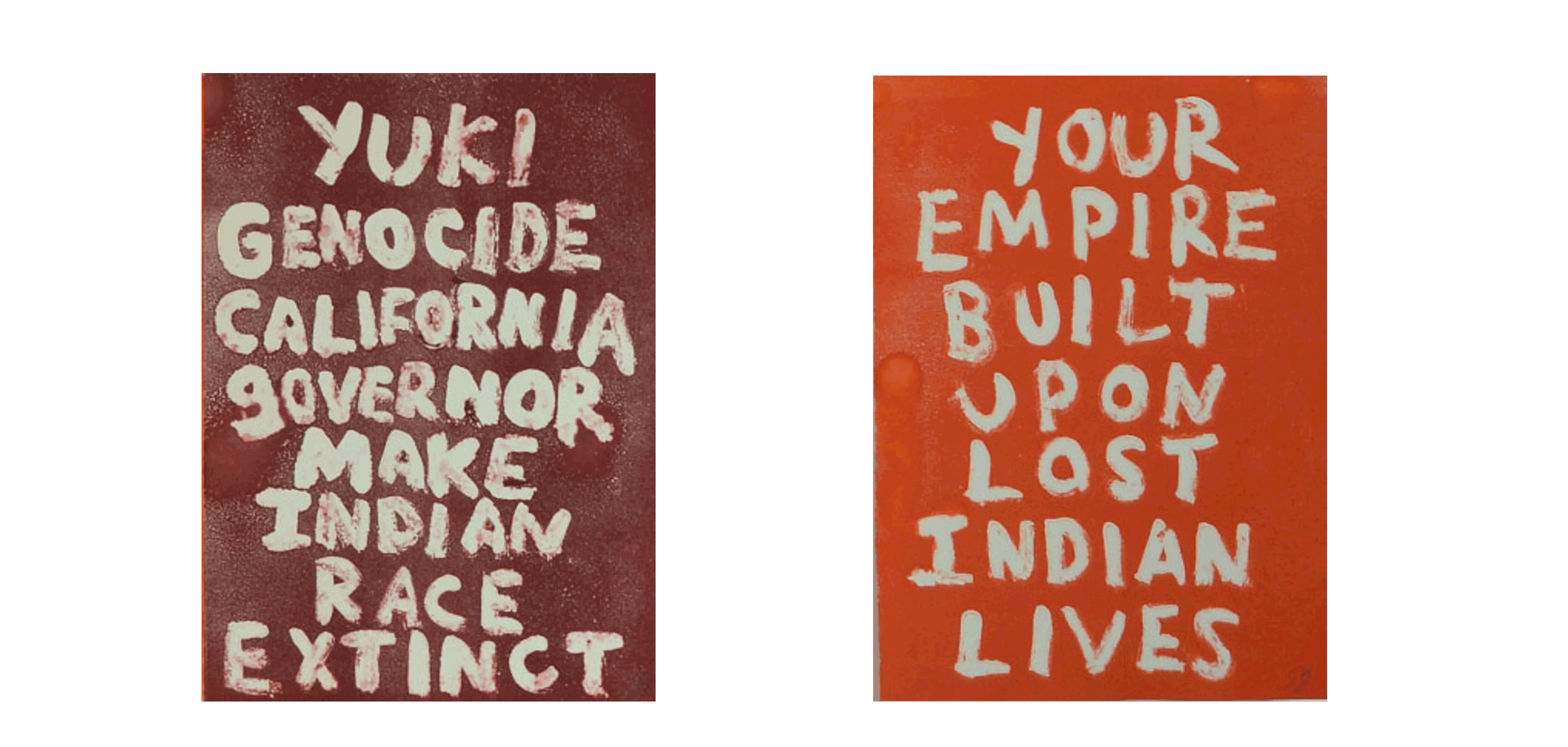

Edgar Heap of Birds, part of the Cheyenne and Arapaho nations, embodies this struggle through his art. Throughout his career, he has brought visibility and justice to the colonial crimes against his people imparted by the settler-colonial project of England and the United States. The themes in "Tribal Lives Matter" resonate deeply with the Palestinian struggle, the condition of apartheid, and systematic political historical erasure and dispossession. This work reveals the ongoing colonial tactics that have been applied at different points in history to various global territories in order to control, settle, and claim indigenous land.

In the 1920s, Zionists made steady progress in their project for a Jewish National Home with some sixty new Zionist colonies established. Jewish land ownership rose from 2.04% of the total area of the country in 1919 to 4.4% in 1929, and immigration increased the Jewish proportion of the population from 9.7% to 17.6% during the same period. Zionist institutions in Palestine continued to assert themselves—in August 1929, the Jewish Agency was created to represent Jewish communities worldwide—and the British continued to privilege Zionist interests over the principle of self-determination or any structures that would have given the Palestinians political power commensurate with their demographic weight.

The number of new Jewish settlers per year:

1931: 4,000

1932: 9,500

1933: 30,000

1934: 42,000

1935: 62,000

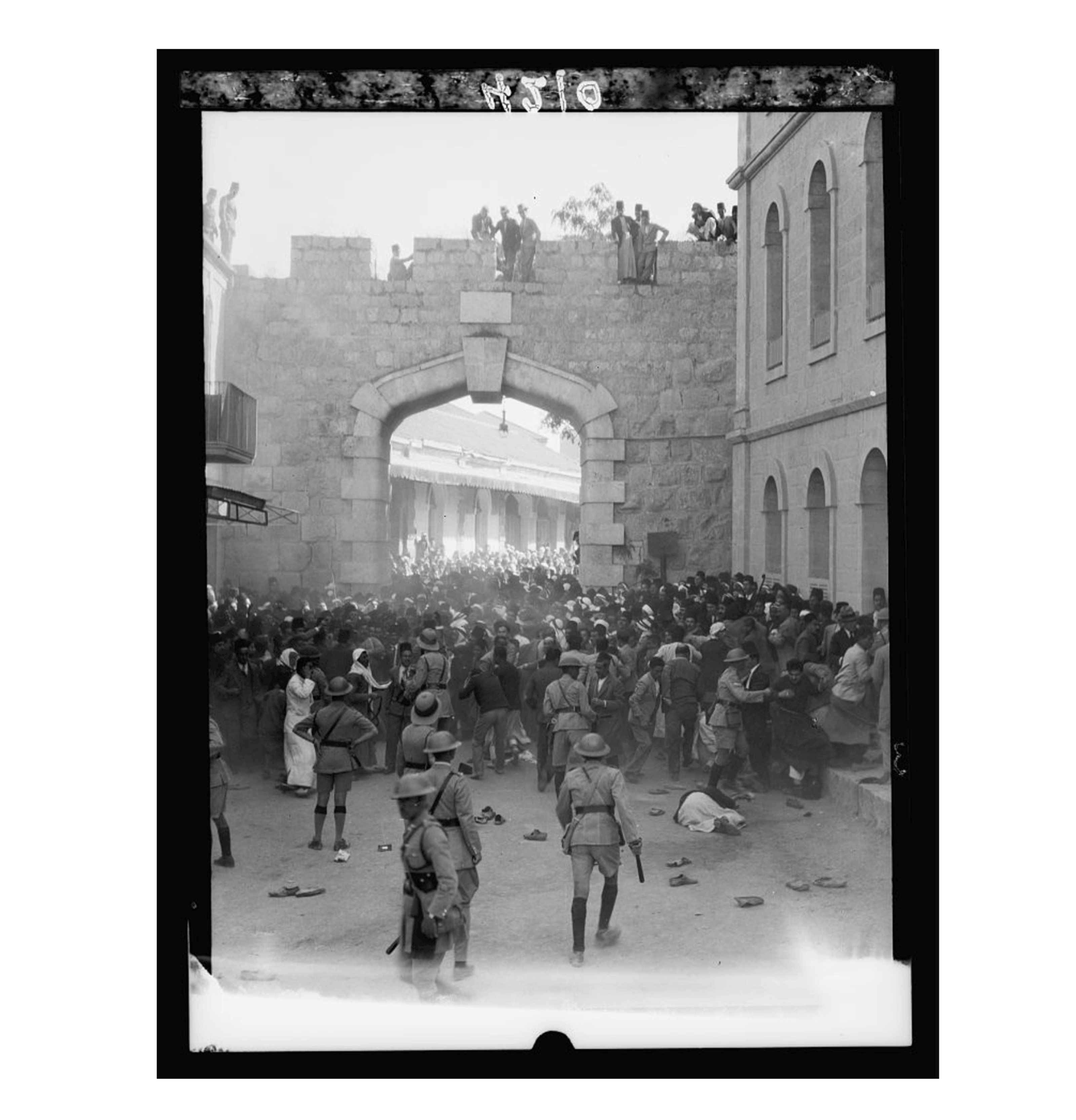

On August 23, 1929, after Friday prayers, Palestinian villagers armed with clubs and swords rushed to Jerusalem upon rumors of Jewish intentions to seize al-Aqsa, marking the beginning of the al-Buraq uprising. A year prior, tensions escalated when Jews installed a divider at the wall during prayer on September 24, 1928. This action was provocative to Palestinians, as proof of Jewish control over the al-Aqsa Mosque, especially in the context of mass migration of European Jews, and the broken promise of an independent Palestine.

Tensions escalated when a faction of Jewish extremists paraded through Jerusalem, reaching the Western Wall where they raised the Zionist flag and commenced chanting the Zionist national anthem, Hatikva. The next day, Palestinians initiated assaults on Jewish neighborhoods but were met by British police waiting for them. Reports of these incidents circulated fast to other cities and Arab towns, prompting marches where some groups targeted Jewish neighborhoods. Most of the Palestinian uprising, however, targeted British mandate government centers and the British police. Police began shooting at crowds, escalating the violence further.

The British Authorities set up a commission of inquiry—the Shaw Commission—to determine the immediate causes that led to the al-Buraq uprising and to make recommendations as to the steps necessary to avoid a recurrence. The Commission submitted its report in March 1930. It identifies Zionist immigration and land practices as the fundamental cause of the disturbances.

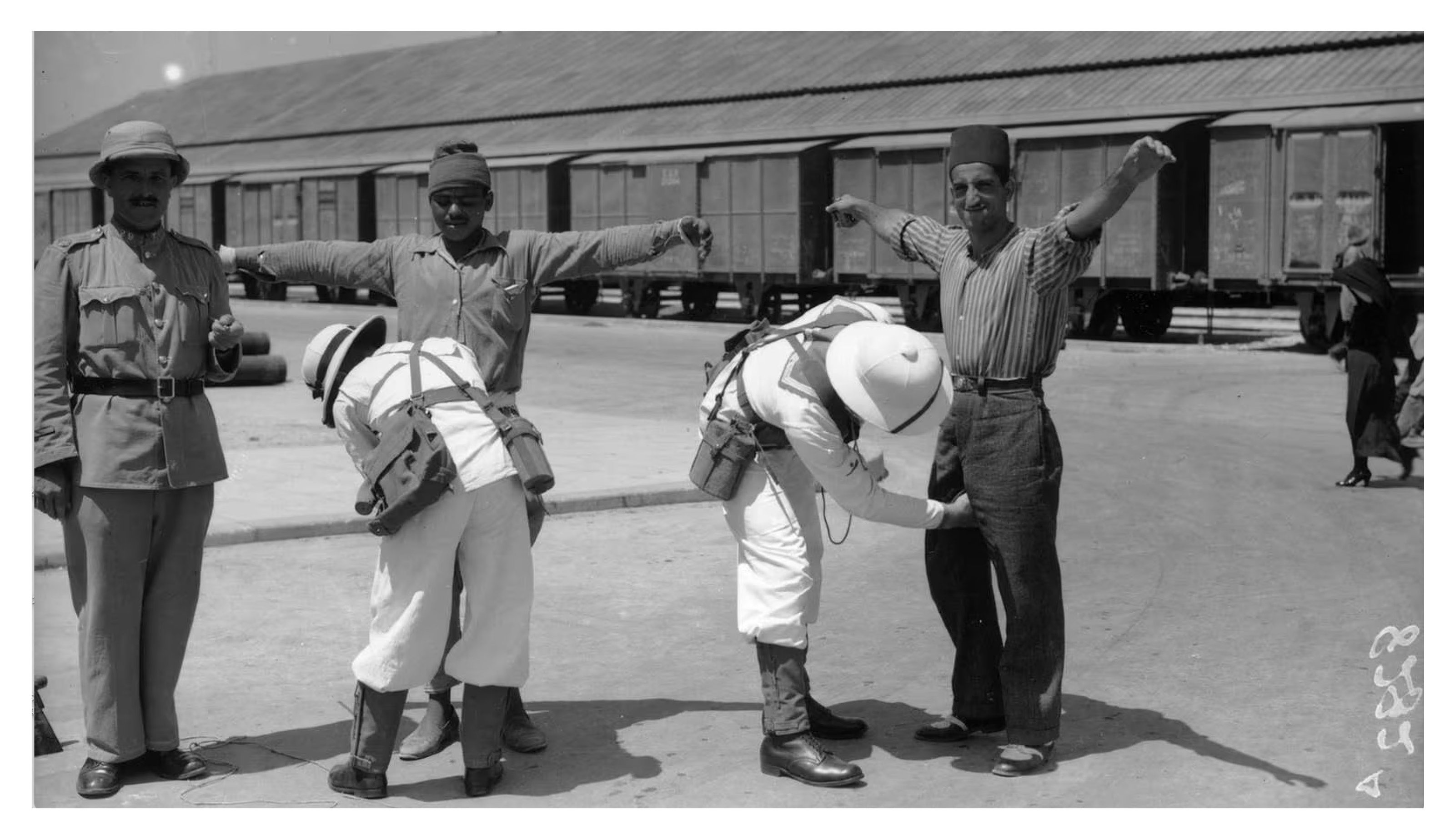

Wailing Wall Commission (Shaw Commission). June and July 1930. Matson Collection, Library of Congress.

Edgar Heap of Birds \ Tribal Lives Matter, 2020

British-appointed Shaw Commission of Inquiry findings.

Israeli commentators discuss successive waves of British-facilitated Jewish migration to Palestine in terms of ‘Aliyah.’ The first Aliyah (1882-1903) witnessed around 35,000 Jews relocating to Palestine, mainly from Russia. They joined approximately 20,000 Mizrahi Jews who had long been established in the region. The second Aliyah (1904-1914) saw another 35,000 arrivals, primarily from the Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire. After the Balfour Declaration, the numbers surged. The third Aliyah (1919-1923) brought 40,000 settlers, followed by 82,000 during the fourth Aliyah (1924-1929), and 250,000 during the fifth Aliyah (1929-1939).

The pre-Zionist Jewish communities in Palestine, which included Mizrahi Jews from Arab countries, experienced a relatively harmonious coexistence with their Palestinian neighbors. For instance, in Jaffa, established Jewish communities of North African descent dressed similarly to their Muslim counterparts and shared the same language. Interactions between various communities were typically characterized by mutual respect. But the arrival of Zionist Jewish settlements from Europe disrupted this dynamic by not adhering to local customs, and their establishment of agricultural settlements sparked fears of a Jewish dominance that would displace the Palestinians.

Zionist settlers embarked on a mission to colonize the land and displace Arabs from areas under their control. Tens of thousands of Palestinian peasants were stripped of their land and migrated to cities, where they struggled to make ends meet in low-paying jobs. The settlers enforced a system where they refused to employ or work alongside Arabs by establishing their own trade union organization—the Histadrut—which exclusively represented Jewish workers. Regular campaigns were conducted to discourage Jews from purchasing goods from Arab markets and farmers.

In this context, during the interwar years, Palestinian movements for national independence intertwined with opposition to Zionist settlements. It became evident that the British-led European Jewish migration to Palestine was closely linked with colonial settlement and the expulsion of Palestinians from their land.

In this double podcast episode about the class struggle in Palestine during the British Mandate (1920-48), Working Class History discusses the organizations built by Palestinian workers, the 1936-39 revolt, and a number of joint strikes by Arabs and Jews which happened against the backdrop of rising tensions culminating in the ethnic cleansing of the Nakba. Part Two. (Podcast)

Formerly known as the Jewish Agency for Palestine, and founded by Chaim Weizmann, the agency played a key role in the creation of the Zionist state of Israel in 1948. It operated as an agency with the aim of promoting Israel to Jewish people originating from other countries, one of which was Russia, encouraging them to settle in occupied Palestine and later become Israeli citizens.

Edgar Heap of Birds \ Tribal Lives Matter, 2020

Adolf Hitler's accession to power in Berlin on January 30, 1933, was soon followed by a wave of antisemitic measures, and the signing of the Haavara Transfer Agreement. Under the supervision of the Jewish Agency, a transfer occurred involving both individuals and capital to British Mandate Palestine. Jewish immigrants to Palestine would reclaim the value of their assets, which were held in escrow accounts in Germany, in exchange for German goods exported to Palestine.

Enabling large-scale Jewish migration to Palestine, the Haavara Transfer Agreement not only marked Germany’s recognition and respect for Britain’s imperial interests, but also served German economic goals—reducing unemployment and bypassing the international boycott campaign that had arisen from Germany’s antisemitic policies—and objectives of racial restructuring. Most importantly, this policy also supported Zionist aspirations to occupy Palestine.

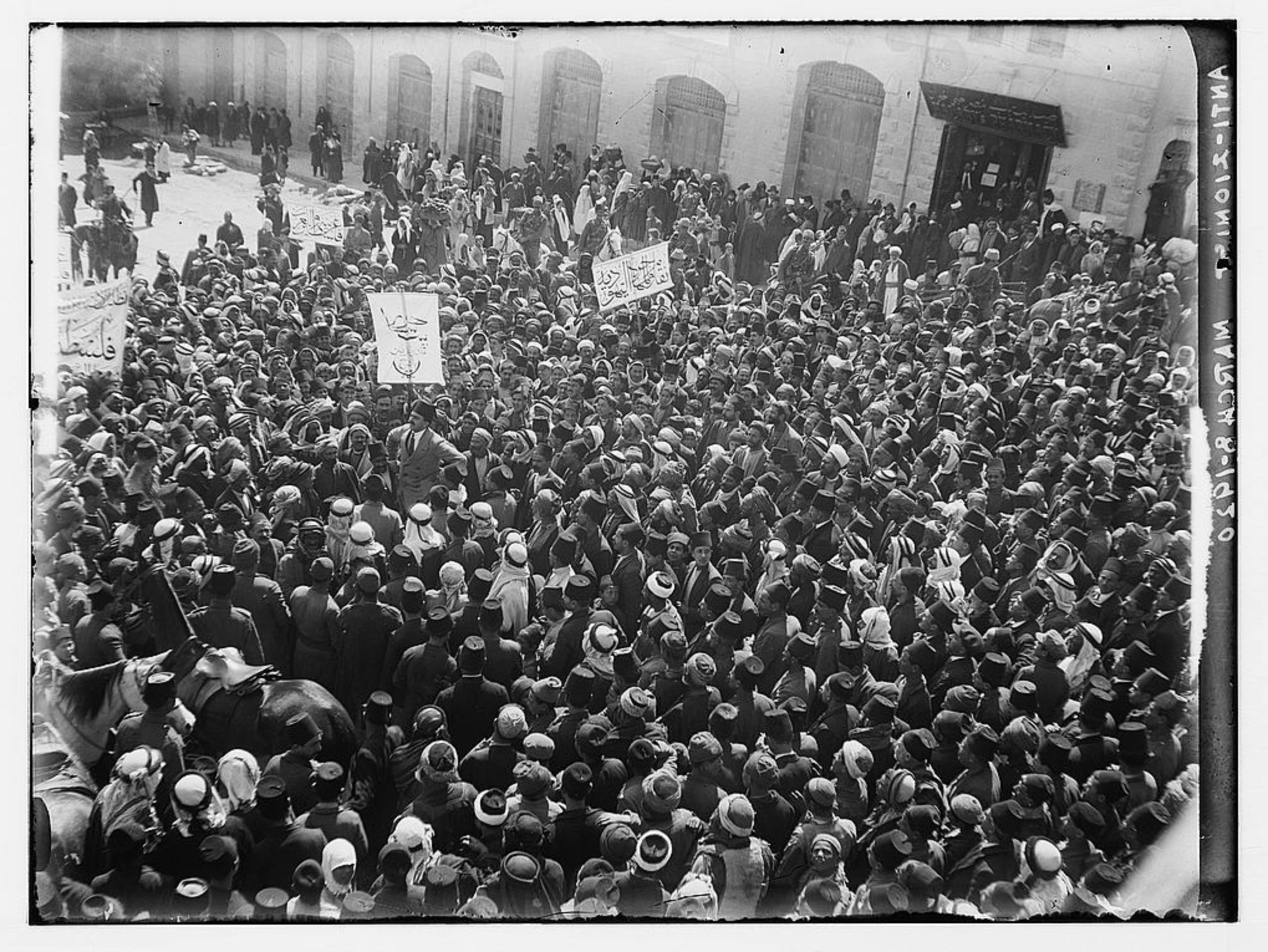

The Arab Executive Committee issued a call for a general strike in Palestine on October 13th, denouncing Jewish immigration and British pro-Zionist policies. Scheduled demonstrations in Jerusalem and Jaffa were met with confrontation by the police. In Jerusalem, led by Musa Kazim al-Husseini, clashes erupted with British police on October 13th, resulting in minor injuries. In Jaffa, on October 27th, police opened fire on demonstrators, killing almost 20 Palestinians, including Musa Kazim al-Husseini, who was struck on the forehead by a mounted British policeman's club. Violence spread to Nablus the same day, to Haifa on October 27th-28th, and to Jerusalem once more on October 28th-29th. Over 30 Palestinians were killed by live ammunition, with 200 sustaining serious injuries. A commission of inquiry, the Murison Commission, has been subsequently convened to investigate the events.

Arab demonstrations on Oct. 13 and 27, 1933. In Jerusalem and Jaffa. Arab disturbances. The aftermath. Feeding from public funds the bereaved and injured. Matson Collection, Library of Congress.

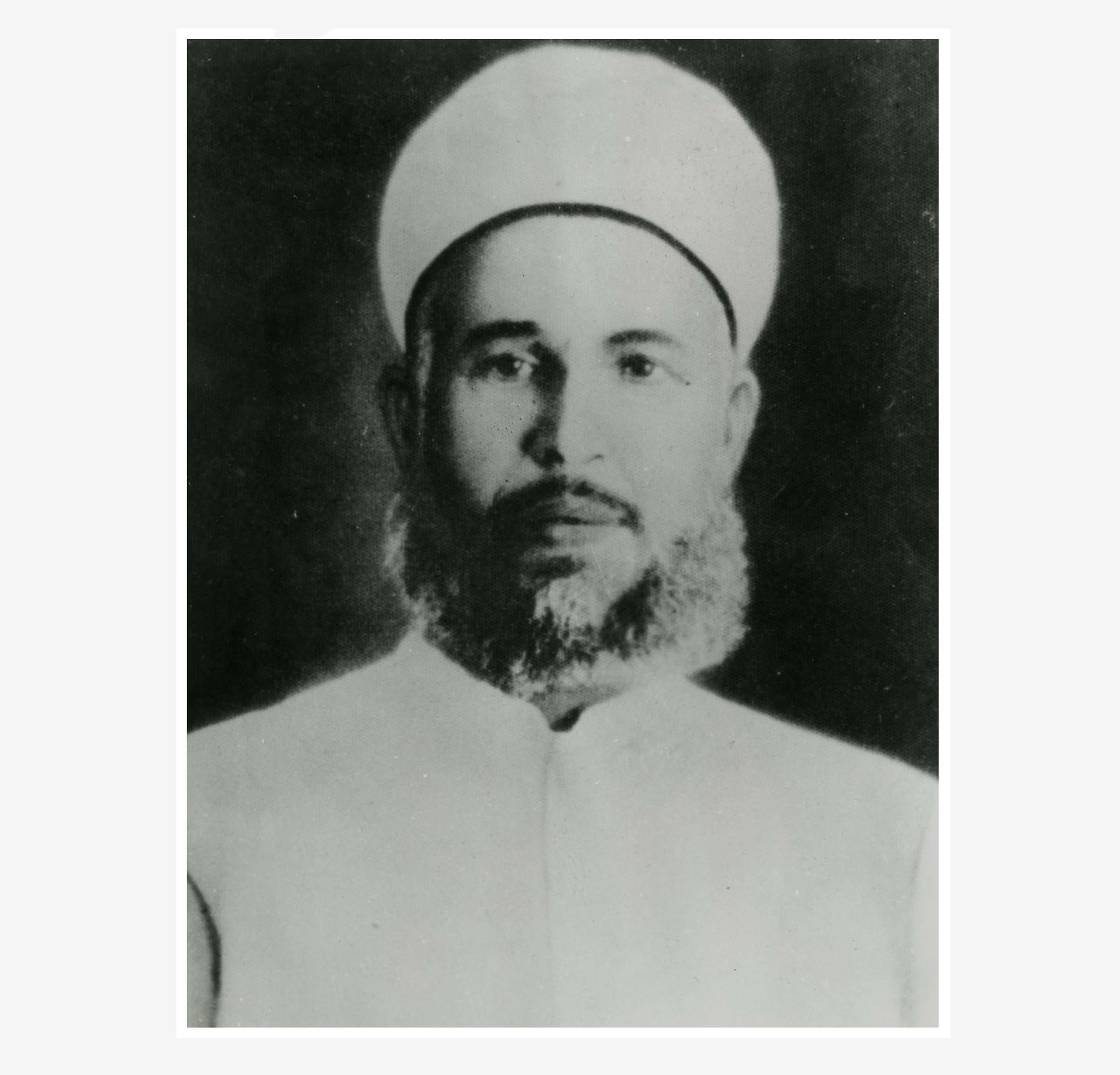

In 1935, Shaykh Izzeddin al-Qassam, a native of the Syrian town of Jabla, a revolutionary leader and the imam of the Istiklal Mosque in Haifa, wrote to the Palestinian leadership in Jerusalem explaining it was time for a more organized resistance against the British Mandate. Palestinian authorities preferred to proceed through negotiations. Al-Qassam went on to form a guerilla group to fight and resist the British Mandate and the Zionist occupation. He was killed in the woods around the village of Ya'bad in the Jenin region after British troops had set an ambush for the guerilla group he was leading. His death resonated deeply across Palestine and contributed to the outbreak of the Arab Revolt in the following year, as many of his followers were still prepared to bear arms to resist and be free from the Zionist national project and British colonialism whenever the chance arose.

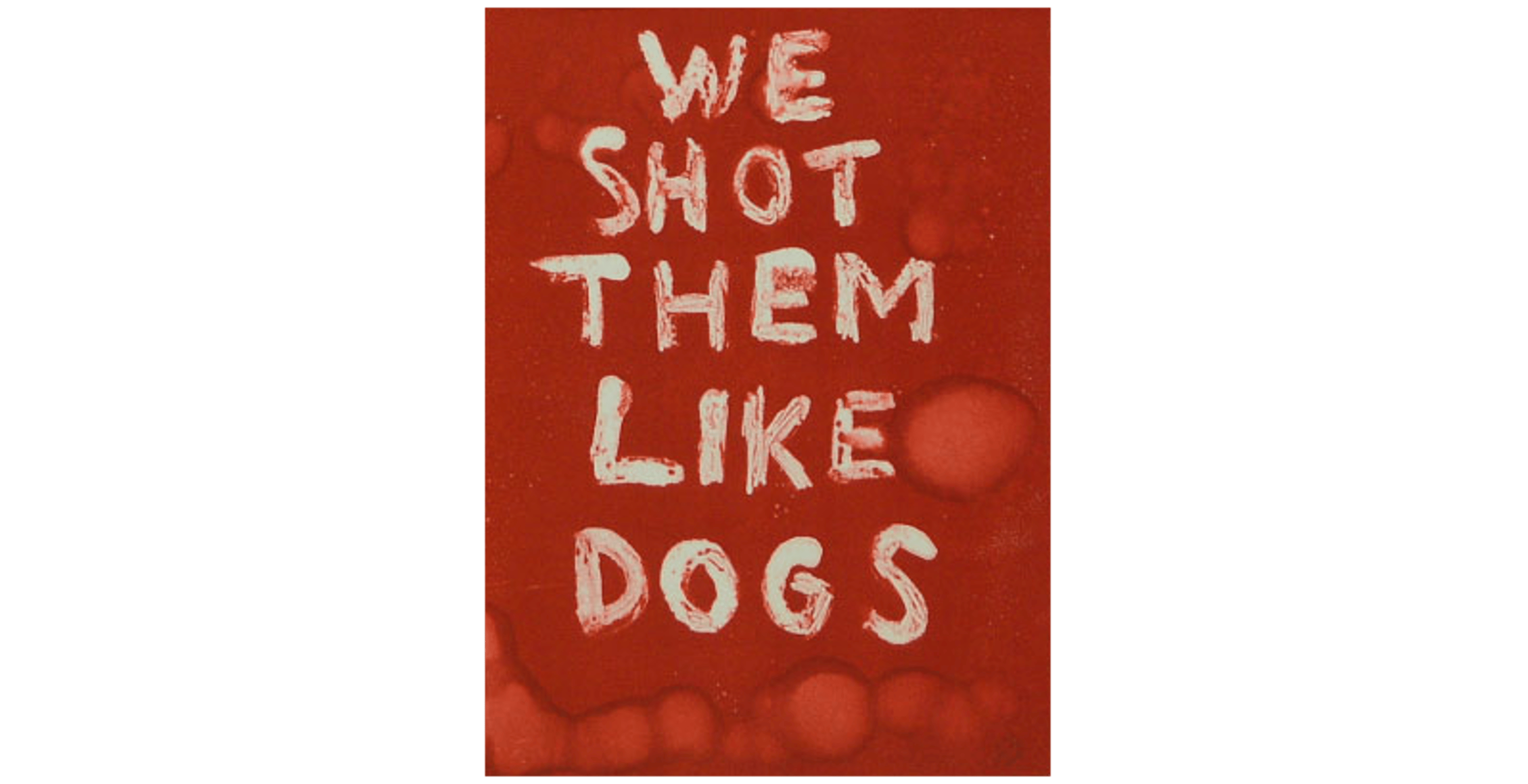

Not Gay as in Happy but Queer as in Free Palestine is a statement that first appeared on placards in Palestinian queer solidarity marches around the globe, and later visualised by artist and designer Marwan Kaabour during Pride Month in 2021.

The design is a creative wordplay, at once championing gay and queer identities, while reminding of alternative readings of queer that signify the other, the unconventional or nonconformist – ideologies that resonate with the struggle for a Free Palestine.

By Working Class History

On 14 December 1936, sexual acts between men were criminalized in Palestine by British colonial authorities.

In the British Mandate Criminal Code Ordinance 1936, Section 152(2), published on this date, so-called “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” was to be punished by a sentence of up to 10 years imprisonment.

In 1951, homosexuality was decriminalized in the West Bank, but as of 2024, the colonial-era law remains in force in Gaza.

Over a decade ago, Palestinian activists adopted the term “pinkwashing” to describe how the Israeli state and its supporters use the language of gay and trans rights to direct international attention away from the oppression of Palestinians. Israeli travel guides and promotional videos advertise Tel Aviv beaches as a gay-friendly getaway destination—and hide the reality that tourist partygoers are dancing atop the ruins of ethnically cleansed Palestinian villages. The open inclusion of gay officers in the Israeli occupation army is used as proof of liberal forward-mindedness, but for Palestinians the sexuality of the soldier at a checkpoint makes little difference. They all wield the same guns, wear the same boots, and maintain the same colonial regime.

The 1930s marked a period of significant economic turmoil in Palestine. Rural Palestinians faced severe challenges due to debt and loss of land ownership, with British policies and the Zionist push for land acquisition and the promotion of "Hebrew labor" only worsening these pressures.

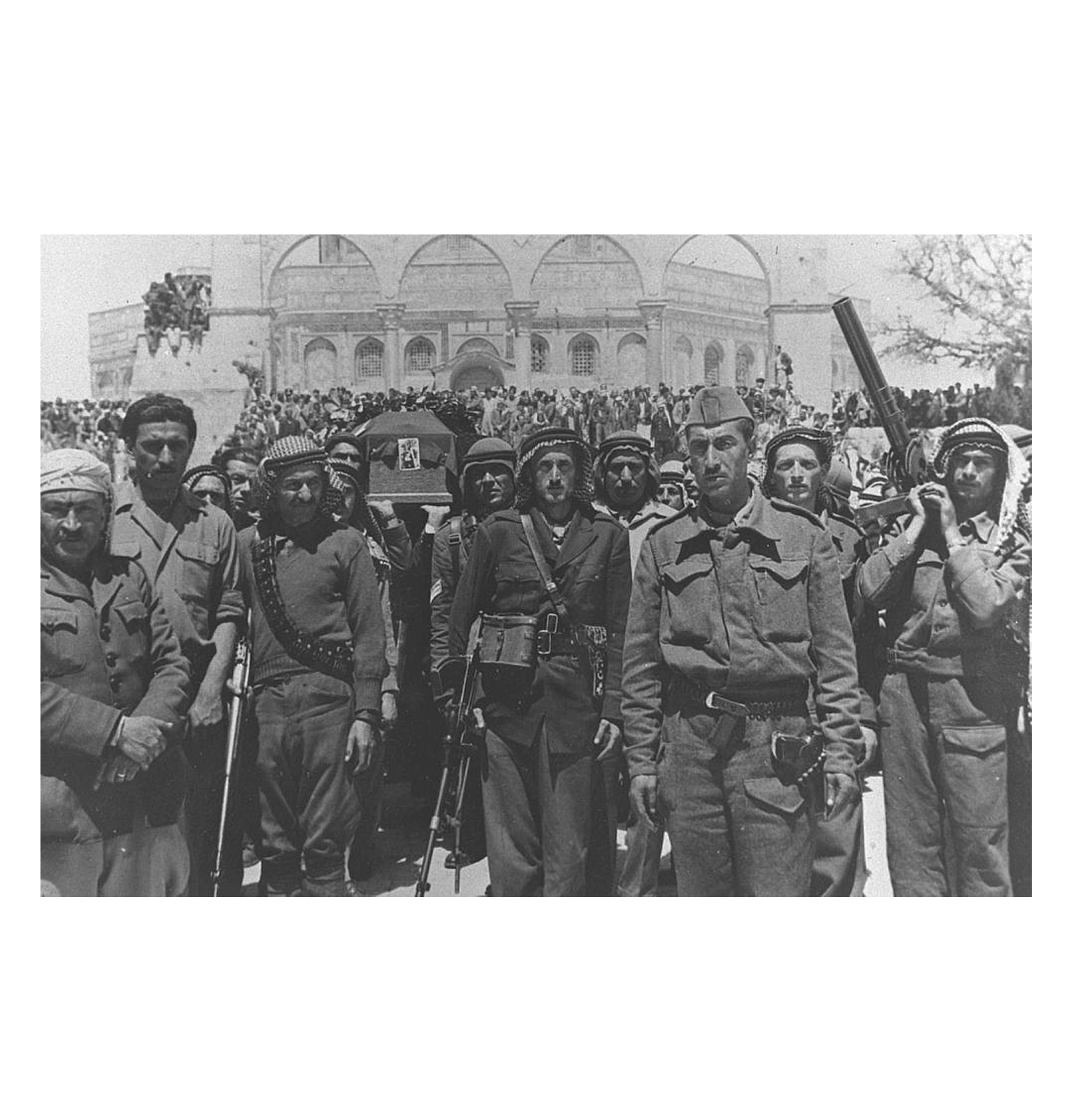

In April 1936, the whole of Palestine went on strike. This was the culmination of frustration towards the preferential treatment by the British of Zionist settlers and the segregation of Palestinians from their land. The Revolt fused basic weaponry and random guerrilla attacks with mass demonstrations and large-scale civil disobedience. It drove Palestinian leaders to quickly unite under the Arab Higher Committee (AHC). This coalition encompassed all Palestinian forces and factions, with Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, elected as its president to articulate their demands. Their objectives included halting forced Jewish immigration to Palestine, ceasing Jewish land acquisition, and establishing a national government accountable to a parliamentary council.

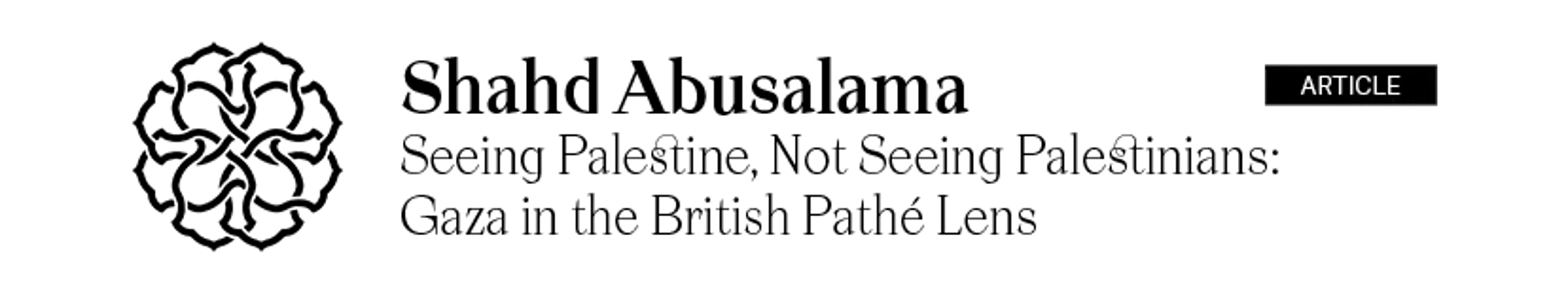

In response to the vast and mostly non-violent action, the British authorities responded harshly, instigating many of the same oppressive methods that are still seen today, such as house demolitions, jailing without charge, detention camps, and executions.

During this time, statements pertaining to the complete erasure of Palestinians were made public through David Ben-Gurion who suggested to the British that the Palestinians should be removed from their land and resettled in Transjordan.

On October 5, 1937, Ben-Gurion wrote a letter to his 16-year-old son, Amos: “We must expel the Arabs and take their places…. And, if we have to use force—not to dispossess the Arabs of the Negev and Transjordan, but to guarantee our own right to settle in those places—then we have force at our disposal.”

Between Haganah and the British troops, the resistance was violently suppressed. In Jaffa, approximately 200 homes were demolished, with more to follow in cities and villages across Palestine.

Approximately 5,000 Palestinians, 500 Jews, and 250 British servicemen died in the aftermath of the strike.

David Ben-Gurion

A Royal Commission headed by Lord Robert Peel—the Peel Commission—was set up by the British to investigate the causes of the rebellion the same year. The commission took two-months to investigate, speaking to both Zionist and Palestinian groups. The recommendations released in 1937 point to partitioning Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state, where the latter would be incorporated into Transjordan, and British Mandatory enclaves. Further, it called for the forced displacement of Palestinians from the Jewish state. This plan was rejected by the Palestinians and served to further inflame the resistance.

The British began dividing Palestine into three zones. In 1937, they went house by house, removing all weapons from the Palestinian people, killing, and destroying food supplies. Since then, Palestinians have been barred from having arms as well as an army, tanks, ships, or combat aircraft.

The sentiments of this report would later come up in recommendations made by the UN, and again by the US in the 1967 Oslo Accords.

Despite Palestinians’ rejection of the report, the British government appointed the Woodhead Commission to investigate the practical implementation of the partition plan.

Palestinian society was drained and worn out after three years of uprising: approximately 5,000 Palestinians were killed, with nearly 15,000 sustaining injuries, and the political leadership was either exiled or killed.

In this context, on May 17, 1939, in order to pacify Palestinians on the eve of World War II, Secretary of State for the Colonies of the British, Malcolm MacDonald, issued the White Paper. It proposed restrictions on Jewish immigration and land acquisitions while pledging an independent unitary state after a decade, contingent upon amicable Palestinian-Jewish relations. Despite its limitations, it appeared to provide some relief from the British Mandate.

Some important points of the proposal included the immigration of no more than 75,000 Jews over the next five years, after which Jewish immigration would be subject to "Arab acquiescence" and land transfers were to be permitted in certain areas but restricted and prohibited in others.

Jewish protest demonstrations against Palestine White Paper, May 18, 1939. Zionist young men & girls parading on King George Ave. [Jerusalem]. Matson Collection, Library of Congress.

The short experimental video examines the network of apparatuses that Israel used to orchestrate its emergence.

It focuses primarily on survey photographs of A -Jaleel captured between 1947 and 1948, which preceded Israel's 1951 National Masterplan. With their manipulative framing and captions, these photographs portray the landscape as "empty." However, they were taken concurrently with ethnic cleansing military operations such as Plan Dalet, Operation Dekel, and others, which aimed to empty the land of Palestinians.

In September 1939, Zionists intensified their efforts to boost Jewish immigration to Palestine amidst mounting urgency. During the war years, the Arab Higher Committee (AHC) and other Palestinian political activity remained illegal, resulting in much of the remaining Palestinian political leadership residing in exile. Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem and head of the AHC, fled to Axis countries in 1941, where he spent the war years—an aspect later exploited by Zionists to allege widespread Palestinian collaboration with Nazism. The reality was different: some 23,000 Palestinians volunteered for service with British forces in North Africa and the Arab Legion.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 briefly quelled the violence as Arabs and Jews from Palestine enlisted in the Allied forces alongside Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union. However, as awareness of the Holocaust grew, the Zionist movement intensified its push for a Jewish homeland.

Increased friction between Britain and the Zionist movement began during the war years. Already strained by Zionist dissatisfaction with the 1939 White Paper, relations deteriorated further as Zionist organizations pressured Britain to raise limits on Jewish immigration to Palestine in light of the ongoing Holocaust in Europe. Illegal immigration continued and British attempts to stop it resulted in the sinking of ships carrying Jewish refugees in 1940 and 1942. Although some 27,000 Jews from Palestine enlisted in the British armed forces, the Zionist Right (Irgun and the Stern Gang) launched violent attacks against British officials, and the Zionist movement more broadly began to seek out alternative sponsorship.

By 1944, Jewish guerrilla groups had broken their truce with British authorities, resuming bombings and other acts of terrorism. This escalation culminated in the assassination of Lord Walter Moyne in Cairo, the British Secretary of State for the Middle East, by the Zionist Stern Gang terrorists.

The Arab Higher Committee (AHC) issued a reply to the White Paper by expressing its appreciation for the British support of the establishment, within ten years, of an independent Palestine State. However, they feared that independence would not be ensured since it would have been conditional on Jewish cooperation and Zionist leaders had already rejected the White Paper. While the AHC appreciated the British stand on Jewish immigration, it stressed that it should be implemented immediately and insisted on "a complete and final prohibition of any transfer of lands from Arabs to Jews."

The AHC strongly criticized the British document for its insistence on "the special position in Palestine of the Jewish National Home” since this meant "the continuance of the calamities which had already befallen Palestine.” The AHC concludes that "it is bound to proclaim, on behalf of the Arabs of Palestine, their refusal of this policy and their inability to cooperate with the British Government in its execution," and affirms their goal of an independent Palestine "within an Arab Federation."

Jumanah Bawazir & Khaled Al Bashir \ Beneath the Infrastructure of Fiction, 2023 (Excerpt)

By Working Class History

On 25 November 1940, a bomb exploded aboard the ship SS Patria planted by the Zionist paramilitary group Haganah, killing 267 people, mostly Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe.

Britain was transporting the refugees away from Palestine to Mauritius.

Haganah intended to disable the ship to prevent British authorities from relocating the refugees, but the bomb caused more damage than intended, sinking the ship and causing many deaths as well as 170 injuries.

In May 1942, a conference was held at the Biltmore Hotel in New York, attended by prominent American Zionists and David Ben-Gurion, representing the Jewish Agency. The rise of Hitler and U.S. entry into World War II led American Zionists in 1942 to adopt the Biltmore Program calling for unrestricted Jewish immigration to Palestine and for turning the territory into a Jewish state. The revelation of the scale of Nazi atrocities boosted U.S. support for Zionism, effectively shifting the center of political Zionism from London to Washington. In addition, the Biltmore Program was also prompted by intense opposition to the MacDonald White Paper.

In January 1945, the U.S. House of Representatives resolved that the United States must facilitate unrestricted Jewish immigration to Palestine in order to reconstitute the country as a “Jewish commonwealth” and the organization of a Jewish army. This was the beginning of direct American involvement in the British handling of the question of Palestine.

The Biltmore Program became the official Zionist stance on the ultimate aim of the movement, which was to colonize Palestine. According to Ben-Gurion, the "first and essential" stage of the program was the immigration of two million additional Jews to Palestine.

Jumanah Bawazir & Khaled Al Bashir \ Beneath the Infrastructure of Fiction, 2023 (Excerpt)

The Alexandria Protocol, issued by representatives of five Arab states (Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Transjordan) meeting in Alexandria, announced the representatives' intent to establish a League of Arab States and their support of the independence of Palestine, and the legitimate rights of the Arabs in Palestine. It called for the distinction between Zionism "and the woes and pains that have befallen the Jews at the hand of some dictatorial European states."

On May 22, 1945, the five states that had issued the Alexandria Protocol, joined by Saudi Arabia and Yemen, signed the Pact of the League of Arab States. The pact was composed of 20 articles stating that the goal of the league "to draw closer the relations between member States and coordinate their political activities" in order "to safeguard their independence and sovereignty." Member states declare that, given the unique situation in Palestine, the League's Council should appoint an Arab delegate from Palestine to engage in its activities until the country achieved genuine independence.

By the end of World War II, the Zionist movement's search for sponsorship had been redirected from Britain to the United States, and the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine) stood positioned to launch political and military campaigns to force Britain out of Palestine and to establish the State of Israel in defiance of Palestinian will.

The Jewish population had swelled from 56,000 in 1918 to 608,000 by 1946, largely due to the Nazi persecution of European Jews. Though Palestinian Arabs sympathized with the plight of European Jews, the sudden immigration brought undue hardship on the Palestinian Arab population.

As the Royal Commission’s report put it:

“An able Arab exponent of the Arab case told us that the Arabs throughout their history have not only been free from anti-Jewish sentiment but have also shown that the spirit of compromise is deeply rooted in their life. There is no decent-minded person, he said, who would not want to do everything humanly possible to relieve the distress of those persons, provided that it was not at the cost of inflicting a corresponding distress on another people.”

In August 1945, U.S. President Harry Truman requested that the British admit 100,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors into Palestine, and in December, the U.S. Congress requested unlimited Jewish immigration into Palestine. American pressure on the British continued into 1946. With the support of a new Great Power sponsor thus secured, the Zionists in Palestine would embark upon a concerted campaign—political and military—to push Britain out of Palestine and impose a Jewish state on the Palestinian population.

III. Zionist and Palestinian landownership in percentages by subdistrict, 1945.

By Working Class History

On 22 July 1946, the Zionist Irgun militia bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 people and wounding 46.

At the time, two thirds of the hotel was occupied by the headquarters of the British colonial administration of Palestine. The plan for the bombing was devised by Irgun leader Menachem Begin, who later became Prime Minister of Israel, and with the collaboration of the Haganah militia.

A warning was given a few minutes beforehand, but not in time to evacuate the building. The Haganah had vetoed two previous plans, and was concerned that given enough time, the British could remove files Zionists believed they held at the building, which they intended to destroy. It turned out, however, that the files were never there.

“Catalogue” addresses the period in which motion-picture newsreel cinema was popular in the West, and film crews came to the Middle East from Britain to document the subjects of their empire. Appropriating the British Pathé (a producer of newsreels and documentaries from 1910 to 1970 in the United Kingdom) news rushes made between 1935 and 1965, “Catalogue” features historic footage interwoven with a Palestinian female protagonist performance as a live, human water feature that magnifies the objectification of Arab women in Western representations. The second half of the video presents the parallel strategy by parties and movements who publicized women fighters as the symbolic countermeasure in representing the liberation struggles of Palestine.

Sama Alshaibi / The Tethered, 2012

By Working Class History

On April 9, 1946, Arab and Jewish workers at the Tel Aviv post office walked out on strike. The next day, they were joined by postal workers across all of Palestine in what would soon develop into a general strike of blue and white-collar public sector workers.

In response to the postal workers' strike, employers quickly made far-reaching concessions, which the Histadrut (the Jewish union federation) recommended employees accept. However, rank-and-file postal workers voted to reject the offer and continue their strike.

On April 14, Arab and Jewish railway workers joined the strike, paralyzing the country's rail system. Middle and lower-level white collar government employees also joined the strike so that, by April 15, 23,000 workers were on strike across the country. It also seemed that oil workers would join the strike, but this was opposed by the Histadrut on the basis that it would harm the broader Zionist project.

Despite this, by the end of April workers had won a number of concessions: an increase in wages and cost-of-living adjustments, and improvements to the pension system. Arab and Jewish communists declared the strike "a blow against the 'divide and rule' policy of imperialism, a slap in the face of those who hold chauvinist ideologies and propagate national division." The Arab Workers' Congress called it a "historic strike […] the first time in Palestine that Arab and Jewish workers have united to show that there are no differences between them and that they have a common enemy."

However, the strike would prove to be a one-off as worker solidarity gave way to ethnic cleansing and the Nakba.

In 1947, Britain officially submitted the “Palestinian question” to the United Nations, marking the first “conflict” in which it was asked to mediate.

The first special session of the United Nations General Assembly convened on April 28, 1947, to consider the question of Palestine. After looking at alternatives, the UN proposed terminating the Mandate and partitioning Palestine into two independent states: one Palestinian Arab and the other Jewish, with Jerusalem internationalized.

One of the two envisaged States proclaimed its independence as Israel and in the 1948 war involving neighboring Arab States expanded to 77 percent of the territory of Mandate Palestine, including the larger part of Jerusalem. Over half of the Palestinian Arab population fled or were expelled. Jordan and Egypt controlled the rest of the territory assigned by Resolution 181 to the Arab State. While the Jews made up one-third of the population at the time, most of them arriving within the last few years, the UN did not consult with Palestinians in drawing up the plan. The Palestinian authorities rejected this plan, with backing from the Arab League.

The Representatives of Arab Countries in the first UN Committee stated:

“The question of Palestine is altogether independent and separate from the question of persecuted persons of Europe. The Arabs of Palestine are not responsible in any way for the persecution of the Jews in Europe. That persecution is condemned by the whole civilized world, and the Arabs are among those who sympathize with the persecuted Jews. However, the solution of that problem cannot be said to be a responsibility of Palestine, which is a tiny country and which had taken enough of those refugees and other people since 1920 … Any delegation which wishes to express its sympathy has more room in its country than has Palestine, and has better means of taking in these refugees and helping them”.

The United Nations partition resolution did not provide a solution to the Palestine problem, and the unrest in Palestine increased. In protest against the partition of their country, the Palestinian Arab Higher Committee called for a general strike. Palestinian-Jewish clashes proliferated with Jewish paramilitary forces operating more freely as British forces started their withdrawal. Sabotage, attacks on military installations and the capture of British arms by these groups became a major feature of the Palestinian scene, along with a proliferation of Jewish-Arab clashes. With events moving towards a major armed confrontation, Great Britain announced that it would terminate the Mandate on 15 May 1948, several months before the time envisaged in the United Nations plan.

This set the stage for the Zionist’s next plan: 1948. This would transform Palestine from what it had been for millennia into a majority Jewish state.

Sama Alshaibi / Generation after Generation, 2019. Screenprint mixed media.

By Working Class History

On 14 February 1947, the British government launched Operation Embarrass: a campaign to bomb and sabotage ships destined to carry Jewish Holocaust refugees to Palestine and blame them on Palestinians.

To this end, the British Secret Intelligence Service (the predecessor of MI6), created a fictional Arab militant group called "The Defenders of Arab Palestine", in order to deter illegal Jewish migration to Palestine, then a British colony.

An internal SIS report admitted that the purpose of the operation was "in fact, a form of intimidation, and intimidation is only likely to be effective if some members of the group of people to be intimidated actually suffer unpleasant consequences."

Embarrass operatives were given the cover story if they were captured that they were in the employ of an anti-communist organization funded by industrialists which claimed that “the Russians were infiltrating Communist Jews into Palestine”.

Over the next year, British operatives attacked five ships before passengers boarded, destroying one and damaging two.

Four Zionist terrorists are executed in Acre prison. Ten days later, a British officer and five security personnel are killed by a car bomb driven by Irgun into a British camp near Tel Aviv.

In June 1947, the Stern Gang claimed responsibility for letter bombs addressed to leading British government officials in London.

Official figures list 75 dead and 196 injured from Zionist terrorist activities against the British since the start of 1947.

Guardian newspaper, June 6, 1947.

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted Resolution 181, which proposed the division of historic Palestine into two separate states – one for the Jewish population and the other for Palestinian Arabs.

The partition plan designated approximately 55% of the land for the Jewish state and 42% for the Arab state, with Jerusalem slated for international administration. Despite Arabs constituting around 67% of Palestine's population at the time, and Jews accounting for about 33%, mainly of recent European immigrants, the Jewish state was allotted more land.

The proposed Jewish state was divided into three largely separate areas: the eastern Galilee, a coastal region including major cities like Haifa and Tel Aviv, and most of the Negev desert. Of the sixteen districts in Mandate Palestine, nine were designated for the Jewish state, with only one having a Jewish majority. Despite this, the proposed Jewish state had an Arab "minority" making up nearly 47% of its population according to the UN proposal.

Shortly after the plan’s approval, violence broke out between the Palestinian Arabs and Jewish Zionists. Zionist paramilitary groups began expelling Palestinians from their properties.

The Arab League, convening in Cairo, denounces the partition of Palestine as illegal and resolves to allocate 10,000 rifles, enlist 3,000 volunteers (including 500 Palestinians), and provide £1,000,000 to the Technical Military Committee.

Britain proposed to the UN that the Palestine Mandate be concluded on May 15, 1948, with the subsequent establishment of independent Jewish and Palestinian states.

In December 1947, a growing number of military actions were initiated against Arab communities, towns, and cities by members of the Haganah and Irgun organizations, including the terrorization of the nearly 75,000 Palestinian residents of Haifa. While the Haganah had been the main Zionist left-wing paramilitary organization since 1920, the Irgun—whose leader, Menachem Begin, later became the prime minister of Israel—was a terrorist group formed in 1931, which specialized in bombing attacks against Palestinians and British authorities.

In response to the attacks, a significant portion of Haifa’s upper class—15,000 to 20,000 people—opted for early departure, seeking refuge in Lebanon and Egypt. From December 1947 to February 1948, assaults conducted by Jewish militias on villages within the Haifa subdistricts resulted in the deaths of 60 to 80 individuals and the destruction of 35 residences. The survivors were forcibly displaced.

On December 31, 1947, the Haganah launched a large assault on the village of Balad al-Sheikh near Haifa, killing 60 to 70 Palestinians, with the Haganah's directive being to target adult males. Moreover, the Haganah General Staff reported that two women and five children were killed, and around 40 individuals were wounded. Several dozen homes were also demolished during the raid.

The Arab League's Technical Military Committee coordinated the establishment of a volunteer force known as the Arab Liberation Army (ALA), led by guerrilla commander Fawzi al-Qawuqji, aimed at aiding Palestinians in resisting partition. The initial contingent of ALA volunteers arrived in northern Palestine. They engaged in clashes with British forces while attacking the settlements of Dan and Kfar Szold.

On January 2nd, the Haganah launched an attack on Abu Shusha village in the Haifa subdistrict.

Two days later, an Irgun car bomb targeted the Grand Serai (Government Center) in Jaffa, killing 26 Palestinians. The following day, the Semiramis Hotel in Jerusalem was bombed, killing 20 Palestinians.

On January 7th, Irgun militants planted explosives at Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem, killing 15 Palestinians and injuring 41 others. On January 11th, combined Zionist forces launched a second assault on the village of Lifta, resulting in the destruction of most houses and the displacement of all Palestinian villagers. On January 19th, the Haganah targeted the villages of Shafa 'Amr in the Haifa subdistrict and Tamra in the Nazareth subdistrict. Later, on January 26th, the Haganah destroyed Sukrayr village in the Gaza subdistrict.

Lifta was among the numerous Palestinian villages violently depopulated by Zionist militias in February 1948. Before its capture, Lifta was home to around 2,900 Muslim and Christian Palestinians who lived in handmade houses, as noted by architect Antoine Raffoul.

Refugees from Lifta recall it as one of Jerusalem's largest and wealthiest communities, with its land once extended from the western hills of Jerusalem to the old city gates. Historical records indicate Lifta’s ancient roots, with its Canaanite origins dating back to Biblical times, known as Nephtoah.

Once the entire village was occupied by Zionist forces, the majority of its inhabitants had already departed for the West Bank, while the remaining few were forcibly transported and abandoned in East Jerusalem. By February 1948, Lifta was completely depopulated by Zionist militias.

The Stern Gang and Irgun seized control of the houses, intentionally damaging the roofs to render them uninhabitable, preventing any potential return of the residents.

The 57 remaining houses were left to decay until Israeli forces demolished them in the 1950s.

According to Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi, a Palmach force raided Sa'sa' village on February 15, detonating explosives in several homes. This destroyed 10 Palestinian houses and resulted in tens of “civilian casualties” according to Haganah.

Prior to 1948, Sa'sa' village was renowned for its location at a crossroads connecting numerous urban areas, notably Safad. It was abundant with water springs, apple and olive orchards, and grape vineyards. In 1949, a Zionist settlement bearing the same name was founded on the former village grounds.

On March 10, 1948, Zionist political and military leaders, including Ben-Gurion, met in Jaffa (Tel Aviv) and formally adopted and launched Plan Dalet or Plan D. It called for:

“Mounting operations against enemy population centers located inside or near our defensive system in order to prevent them from being used as bases by an active armed force. These operations can be divided into the following categories:

Destruction of villages (setting fire to, blowing up, and planting mines in the debris), especially those population centers which are difficult to control continuously;

Mounting search and control operations according to the following guidelines: encirclement of the village and conducting a search inside it. In the event of resistance, the armed force must be destroyed and the population must be expelled outside the borders of the state.”

Villagers evacuating Qaluniya, a village on the outskirts of Jerusalem on the Jaffa-Jerusalem highway. As one of the primary targets of Operation Nachshon, Palmach units attacked Qaluniya on April 11, 1948, just two days after the Deir Yassin massacre. They destroyed all the houses and left the village in flames. Getty Images.

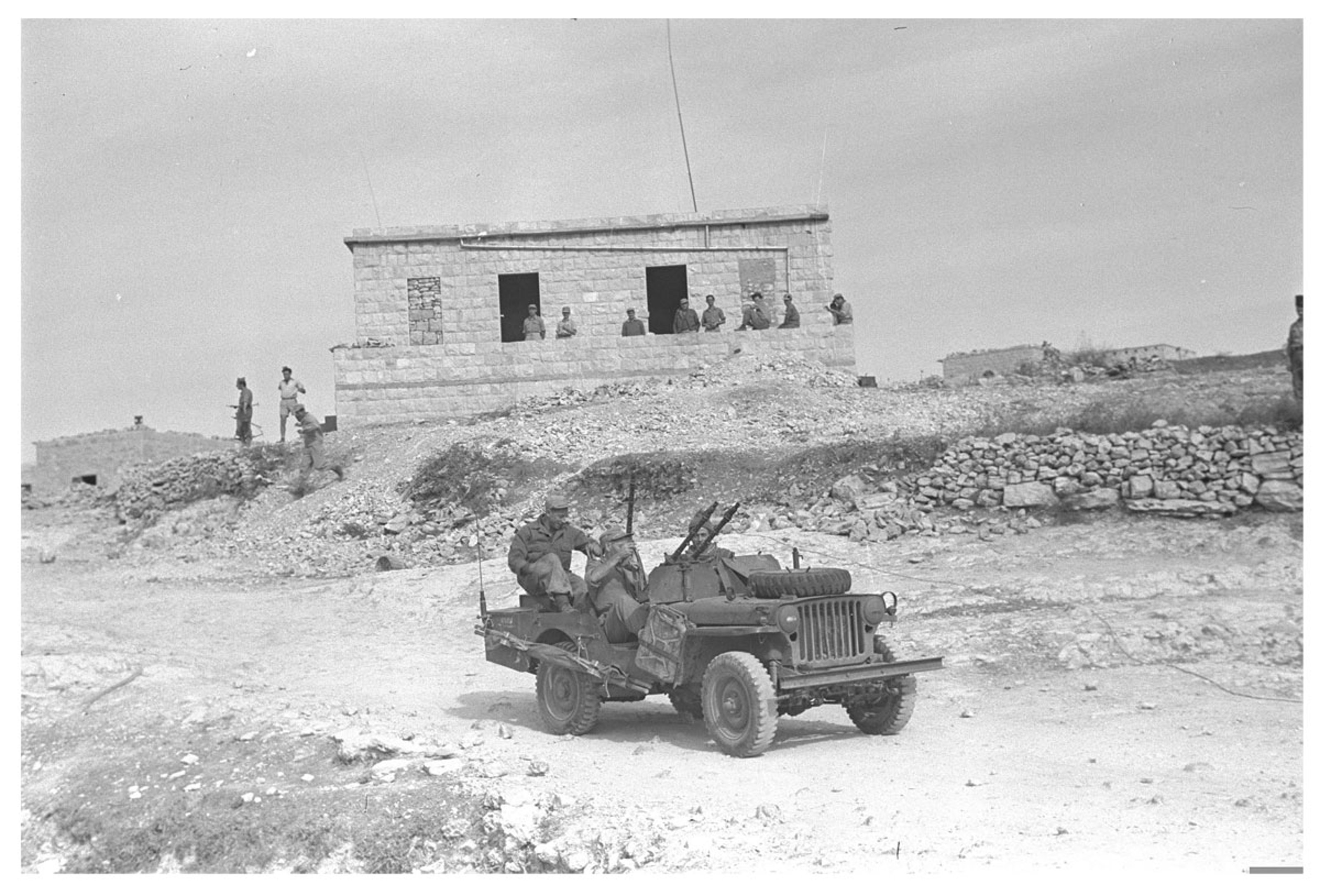

Operation Nachshon was the first pillar of Plan D, with the goal of shifting from intermittent assaults on the Palestinian populace to broad and coordinated operations aimed at seizing maximum territory possible prior to the conclusion of the British Mandate.

From March 31 to April 1, 1948, Ben-Gurion and members of the Haganah General Staff decided to launch a special operation to overrun the villages on both sides of the highway from Jaffa (Tel Aviv) to Jerusalem. About 1,500 Palmach and Haganah troops were mobilized, stating that "all the Arab villages along the [Khulda−Jerusalem] axis were to be treated as enemy assembly or jump-off bases."

The operation began with the occupation of Dayr Muhaysin and Khulda on April 3, followed by an attack on Qalunya on April 11.

The New York Times reported that Haganah units "blew up a score of houses and left the entire village ablaze."

Affected Villages: al-Mansura, al-Mukhayzin, al-Qastal, Bayt Mahsir, Bayt Naqquba, Bayt Thul, Bayt Susin, Bayt Jiz, Dayr Ayyub, Dayr Muhaysin, Deir Yassin, Khirbat Bayt Far, Khulda, Nitaf, Qalunya, Sarafand al-Kharab, Saris, Saydun, Umm Kalkha, Wadi Hunayn.

Ilan Pappé, Israeli historian

On April 4, Fawzi al-Qawuqji launched an attack on the Zionist colony of Mishmar ha-'Emeq, agreeing to a ceasefire the next day for the evacuation of civilians.

Haganah occupied several villages southeast of Haifa, aiming to cut the city off from its surrounding hinterland.

On April 10, Haganah counter-attacked Qawuqji's forces near Mishmar ha-'Emeq and captured neighboring villages. On April 16, the Haganah occupied Palestinian Druze villages.

On April 18, Tiberias became the first Arab town to be captured by the Haganah.

Palestinian historian, Walid Khalidi, contends that a crucial factor in Tiberias' fall was the British handling of the situation. Until their scheduled withdrawal on May 15, as the mandate authority, it was their responsibility to maintain peace and security in Palestine. Yet, amidst heavy mortar fire in Tiberias, the only action taken was an “advice” to the commander Arab garrison “to stop fighting and evacuate the Arab inhabitants.”

On April 21, the sudden withdrawal of the British from Haifa removed the buffer zone, enabling Haganah to capture the city on April 22 and forcibly displaced the Palestinians. Haifa was home to a mixed community of Arabs, Jews, and Christians. Within one week, almost 50,000 Arab inhabitants were expelled from their land to Lebanon and Egypt.

The attacks were not an isolated phenomenon, nor were they prompted by any local Arab action.

The military and political circumstances leading up to and following the Deir Yassin Massacre rendered it as a pivotal moment in 1948, clearly showing the Zionist agenda to steal Palestinian land and expel Palestinians from their homes.

Deir Yassin, situated on a hill facing West Jerusalem, was surrounded by Jewish settlements, forming a barrier between the village and the city. The village had approximately 750 Palestinian residents who resided in 144 houses, according to the Institute for Palestine Studies, and stands out as one of the most dreadful occurrences of the Palestinian exodus.

On April 9, 1948, the village was brutally attacked by the Irgun and Stern Gang, with assistance from the Haganah. When the terrorist groups entered Deir Yassin, the assault resulted in indiscriminate massacres, brutal killings, and the looting of Palestinian homes. Using brutal methods (including blowing up houses with residents trapped inside), they killed indiscriminately—men, women, children, the elderly—and openly desecrated their bodies. The attackers then looted the village.

The groups loaded 150 of the Palestinian villagers taken as prisoners (referring to them as “enemy combatants”) onto trucks, paraded them in a victory procession in Jewish neighborhoods, and dumped them on the outskirts of the Arab neighborhoods in order to create more fear and flight.

Survivor testimonies of the massacre abound with descriptions of the brutality exhibited by the perpetrators; numerous individuals bore witness to the annihilation of entire families and provided detailed accounts of the victims' identities.

After carrying out the massacre, the terrorist groups convened a press conference exclusively for the American print and radio media, where they bragged about the military victory and occupation of Deir Yassin and massacre of Palestinians.

Jacques de Reynier, the head of the International Committee of the Red Cross delegation in Jerusalem, witnessed the aftermath of the massacre firsthand, describing piles of corpses everywhere.

Palestinians tried to mobilize public opinion around the world through the press and whatever platforms they could use to spread the news of the massacre as widely as possible, but Deir Yassin had been abandoned to fight its battle on its own.

Following the massacre, Deir Yassin's remaining homes were converted into a psychiatric hospital by the Israeli government.

Operation Yiftach aimed to seize control of Safad, an important city in northeastern Palestine. Zionist attacks began on the village of Akbara to intimidate the residents of Safad. The final assault on Safad occurred May 10-11, 1948, leading to the forced departure of Palestinian residents from nearby villages. After Safad was occupied by Zionist militia, the operation focused on blocking entry routes for Lebanese and Syrian forces before May 15 -the alleged date of British withdrawal from the area.

On May 14-15, the Palmach's First Battalion advanced on Qadas and al-Malikiyya, capturing Qadas briefly before being forced to withdraw by a Lebanese counteroffensive.

Despite this setback, Lebanese forces were halted at Qadas due to heavy losses and Zionist militia raids into Lebanon.

Affected Villages: Abil al-Qamh, 'Akbara, al-'Ulmaniyya, al-Butayha, al-Dawwara, al-Dirbashiyya, al-Farradiyya, al-Hamra', al-Husayniyya, al-Manshiyya, al-Mansura, al-Muftakhira, al-Nabi Yusha', al-Qudayriyya, al-Salihiyya, al-Samakiyya, al-Sanbariyya, al-Shawka al-Tahta, al-Shuna, al-Tabigha, al-Zawiya, al-Zuq al-Fawqani, al-Zuq al-Tahtani, 'Ammuqa, 'Arab al-Shamalina, 'Arab al-Zubayd, 'Ayn al-Zaytun, Baysamun, Biriyya, al-Buwayziyya, Dallata, Fir'im, Ghuraba, Harrawi, Hunin, al-Ja'una, Jubb Yusuf, Khirbat al-Muntar, Khiyam al-Walid, Kirad al-Baqqara, Kirad al-Ghannama, Lazzaza, Mallaha, Mirun, Mughr al-Khayt, al-Na'ima, Qabba'a, Qadas, Qaddita, Tulayl, Yarda, al-Zanghariyya, al-'Abisiyya, al-Khalisa, Khan al-Duwayr.

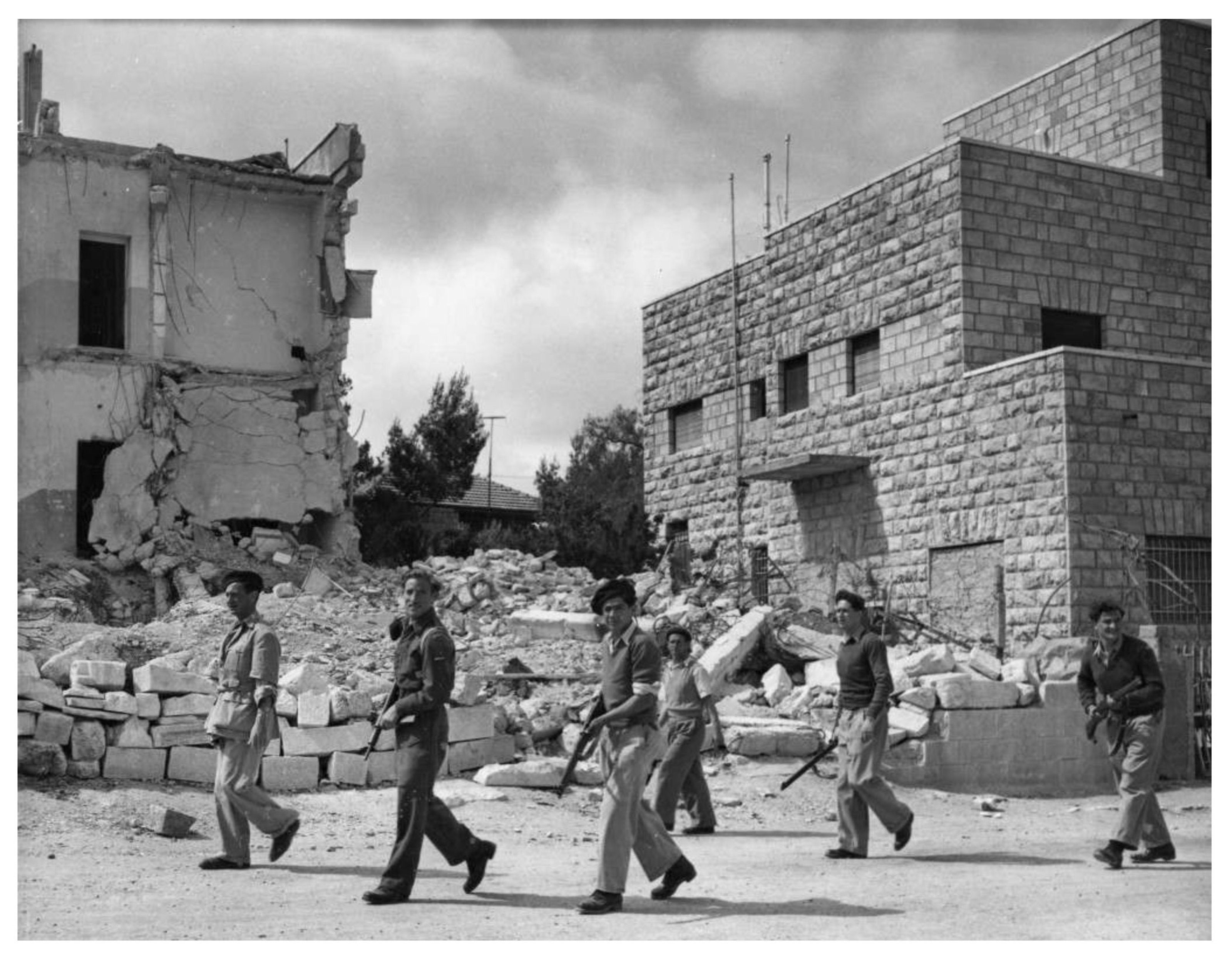

The primary goal of Operation Hametz was to capture the large Palestinian villages situated on both sides of the railway connecting Jaffa - the largest Palestinian city with more than 70,000 indigenous inhabitants- to its Arab hinterland.

The execution of Operation Hametz faced complications due to a frontal assault on Jaffa initiated by the Irgun Zvai Leumi (IZL), operated under Haganah command, contributing to the effective shelling of Jaffa on April 25. This attack aimed to isolate the Manshiyya quarter from the main part of Jaffa, with plans to extend the assault throughout the city. Despite determined resistance, Manshiyya fell on April 29.

On May 11, the Haganah occupied Jaffa. The British departed the area the following day and 120,0000 Palestinians in Jaffa were forcibly displaced by the Zionist forces.

Jaffa is considered to be one of the oldest port cities in the world, dating back to the Bronze Age. Approximately 15% of all Palestinian refugees trace their origins back to Jaffa.

Between 1949 and 1992, the Tel Aviv municipality, which had illegally absorbed Jaffa after Israel's illegal establishment in 1948, and confined its Palestinian population to a restricted area, designated it as a slum zone earmarked for demolition.

The book titled "The Conquest of Jaffa" by Haim Lazar (1951) was later retitled, replacing "conquest" with "liberation." Lazar characterized the actions of Zionist militia in Jaffa as "cleansing." However, when later scholars like Meron Benvenisti and Ilan Pappé employed the term "cleansing," it sparked controversy and was seen as “provocative”.

Affected Villages: al-’Abbasiya, al-Khayriyya, al-Safiriyya, al-Sawalima, Bayt Dajan, Kafr ‘Ana, Salama, Yazur.

The Haganah launched Operation Jevussi to conquer all of Jerusalem, including Palestinian residential areas in both West and East Jerusalem outside the Old City, along with villages in the northern and eastern suburbs. Despite initial attacks and attempts to cut off Jerusalem from Jericho, British intervention helped the Haganah to occupy the Palestinian quarters in West Jerusalem, resulting in the expulsion of residents.

Zionist forces seized control of several Palestinian residential areas in western Jerusalem, including Katamon, Talbiyya, the German Colony, the Greek Colony, Upper Bak'a, and Lower Bak'a. This led to the expulsion of much of the Palestinian cultural, political, and intellectual elite, who were forced into exile. Their properties, including valuable library collections, were confiscated by Zionist paramilitary groups. The displaced Palestinians sought refuge in nearby Ramallah, Bethlehem (in the West Bank), and Jordan. Talbiyya, once an affluent Palestinian Christian neighborhood, was transformed into an upscale Israeli Jewish area known as Komemiyut.

This chapter is a decolonial initiative that critically engages with the representation of the Palestine question in general and Gaza refugees in particular by British Pathé, which, as a leading media institution of the British Empire, was also a dedicated advocate of Zionist ambitions and Jewish settlement in Mandate Palestine. I interrogate Pathé’s discursive strategies in representing the 1947–48 Nakba, the 1956–57 Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip, and Israel’s subsequent occupation of Gaza beginning in 1967. Highlighting strategies of inclusion and exclusion, deconstructing a one-sided historical narrative written by the victor, and contextualizing that narrative in the suppressed past of the subaltern, I argue that British Pathé provided a consolidating, hegemonic discourse on Palestine-Israel that prevails to this day in mainstream political, media, and academic discourse.

The Nakba, meaning catastrophe in Arabic, is more than a historical event for Palestinians; it signifies an ongoing process that began with Western Zionist settlers arriving in Palestine in the 1880s.

From December 1947 to May 14, 1948, around 175,000 Palestinians were forcibly removed from their homes, while approximately 200 villages and urban areas were occupied and destroyed by Zionist militia.

On May 14, 1948, the Zionist occupier state of Israel was declared without agreement from Palestinians, just a day before the British Mandate officially ended. Following this declaration, Arab armies intervened in Palestine to counter Israeli military advancements.

Surprisingly, the term "Nakba" referring to the Palestinian catastrophe was initially used by the Israeli military. In July 1948, the IOF distributed leaflets to Arab residents of Tirat Haifa who resisted occupation. In Arabic, they urged surrender, stating "If you want to be ready for the Nakba, to avoid a disaster and save yourselves from an unavoidable catastrophe, you must surrender.” Despite the Zionist project succeeding in establishing Israel in 1948, Palestinian displacement has persisted.

By the end of 1949, more than 750,000 Palestinians, out of a population of 1.9 million, were expelled from their land and more than 500 Palestinian villages were destroyed by the Zionist occupation. Most of the indigenous population fled to neighboring countries as refugees.

Palestinian Refugees in 1948 Leaving the Galilee. Photo: Fred Csasznik/Wikimedia Commons.

During the Nakba, where hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes, both Zionist forces and Jewish civilians participated in extensive looting, which persisted for several months. John Rose, an Armenian resident of Jerusalem, witnessed this rampant pillaging in al-Baq‘a, where Jewish residents roamed freely, plundering Arab houses on a massive scale:

During this time looting of Arab houses started on a fantastic scale, accompanied by wholesale vindictive destruction of property . . . From our verandah we saw horse-drawn carts as well as pick-up trucks laden with pianos, refrigerators, radios, paintings, ornaments and furniture . . . Safes with money and jewelry were pried open and emptied . . . Our friends’ houses were being ransacked and we were powerless to intervene . . . This state of affairs continued for months.

Israeli historian Adam Raz notes that the looting spread rapidly among Israelis after the establishment of the state in May 1948, affecting tens of thousands of Palestinian homes, stores, and factories. The stolen items ranged from mechanical equipment and farm produce to personal belongings like clothing and jewelry. Yair Goren, a Jerusalem resident, described the chaotic scene, with people frantically gathering loot as if in a trance.

Zionist military commander, Moshe Salomon, detailed this disturbing phenomenon in his diary: “We were all swept up by it, privates and officers alike. Everyone was seized by a craving for possessions. They rummaged through every house, and some found food, others found expensive objects. The mania attacked me, too, and I was barely able to stop myself.”

Moshe Salomon

Zionist Military Commander, Jerusalem

Jewish Israelis looting the depopulated homes of wealthy Palestinians in Musrara neighborhood. Tarek Bakri.

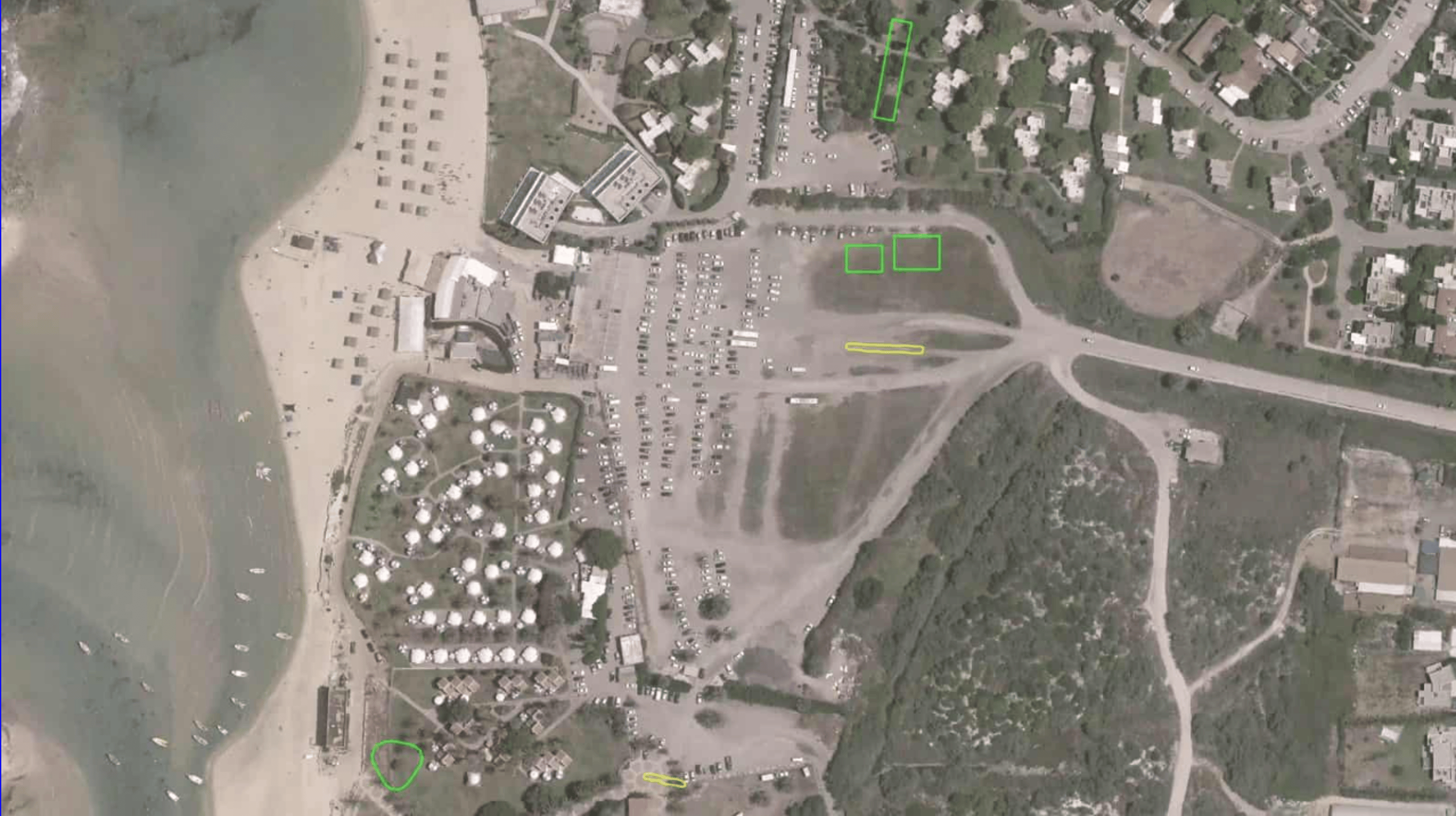

On the night of 22-23 May 1948, one week after the establishment of the State of Israel, the Palestinian fishing village of Tantura was attacked and occupied by the 33rd Battalion of the Alexandroni Brigade, later made part of the Israeli army. Within hours of occupying the village, Israeli forces and intelligence units conducted a systematic massacre of disarmed Palestinian fighters and civilians.

Both the historical record and the testimonies of survivors captured by scholars and filmmakers reference the existence of several mass graves dug in Tantura on the 23rd of May 1948. These graves had been created to hold the bodies of Palestinian civilians and fighters killed during the battle for control of the village, as well as those executed after its occupation.

The Tantura Massacre occurred after the al-Tantura village had surrendered and, akin to numerous other villages across Palestine, constituted a component of systematic efforts by the settler state of Israel to forcibly relocate hundreds of thousands of Palestinians.

Al-Tantura, a fishing village near Haifa, home to almost 1,500 Palestinians, was one of the last remaining Palestinian villages following the state of Israel’s establishment. The village was destroyed and nearly 200 unarmed Palestinians were executed by the 33rd Battalion of the Alexandroni Brigade, a Zionist militia which was later absorbed into the IDF. The victims’ bodies were dumped into a mass grave, later to become a car park for nearby “Tel Dor” beach.

After the massacre, women and children were moved to Furaydis while the men who survived were sent to prison camps.

The Tantura massacre was largely overlooked until it came to light with the work of Haj Muhammad Nimr al-Khatib, a former member of the Arab National Committee of Haifa. Around 1950, Khatib published "Min Athar al-Nakba"(Consequences of the Catastrophe) in Damascus, containing his memoirs and testimonies of Palestinian refugees. This work, along with others, was translated into Hebrew in 1954 by the Israel Defense Forces and published as "Be'einei Oyev" (In Enemy Eyes).

The Israeli-produced documentary film “Tantura”, in which several Israeli veterans were interviewed and confirmed the atrocities committed against Palestinians, faced massive censorship upon its release in 2022.

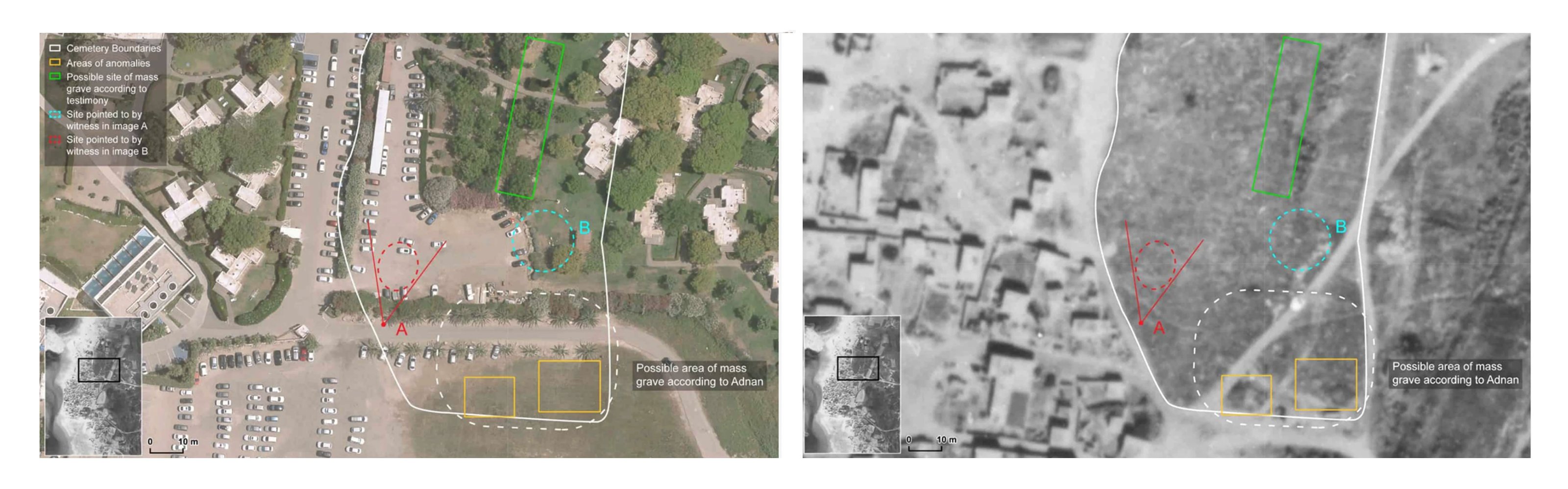

Forensic Architecture analyzed aerial photos from the British Mandate.

The United Nations announced a ceasefire that commenced on June 11th and lasted for 28 days. This truce was supervised by UN mediator Folke Bernadotte and a team of UN Observers, consisting of army officers from Belgium, the United States, Sweden, and France.

Contemporary satellite imagery showing sites of possible mass graves in Tantura. Source: 7 June 2019, OFEK. (Forensic Architecture, 2023)

Excerpt from Executions and Mass Graves in Palestine by Forensic Architecture.

Lydda and Ramla were known as twin cities, merely three kilometers apart. Initially designated to be part of the Arab state under the UN Partition Plan of November 1947, Zionist forces occupied them both in July 1948. Shortly before the assault on Lydda and Ramla, Israeli warplanes conducted extensive bombing raids on the towns during the early evening hours, coinciding with Muslim residents breaking their fast for Ramadan.

On July 11th, Israeli aircraft dropped leaflets that called on the people of Lydda to “surrender and leave the city before it collapsed on their heads.” Despite initial resistance from city defenders, the onslaught persisted and by the evening, Israeli forces entered the city, unleashing indiscriminate gunfire upon Palestinians seeking shelter in mosques and homes. The death toll surpassed 400.

Zionist leaders expelled the remaining Palestinian population to Ramallah (West Bank).

Sana Hammoudi recounts the massacre perpetrated by Zionist forces in Lydda in July 1948, as well as the forced expulsion of 70,000 Palestinians during what became known as the "march of death."

Ramla remained under the guardianship of its young Arab defenders, equipped with a few old rifles and homemade rockets, which they fired from the cover of tree branches. The inhabitants of both Lydda and Ramla were compelled to depart on foot, making their way to the West Bank devoid of provisions such as food and water.