According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, to look is to direct your eyes in a particular direction; to see is to notice or become aware of something by using your eyes. We might be able to make a few distinctions here. Looking seems to be a more passive action of receiving information while seeing involves the active digestion of information. Plus, looking is more of a physical activity, whereas seeing is a mental process of perception. In order to see an object, we need to look at it first.

Photo by Alicia Steels on Unsplash

Mona Lisa, one of the most famous artworks in the world, welcomes about 30,000 viewers per day at the Louvre. After waiting in lines for some time, viewers are carried by the human flow, urged by the museum staff to leave the gallery in less than a minute. What they get to see in this minute is the Mona Lisa, a 30 in. to 21 in. sized painting, behind rows of hands, heads, and smartphone screens. A few years ago, the Louvre found that people study the Mona Lisa for an average of just 15 seconds. The word study here is likely an overstatement. Between “look” and “see”, “look” seems to be the appropriate action.

It’s rather hard to blame the Louvre for this deformed experience if we take into account the volume of viewers the painting has to accommodate and the extra security it demands. Even without such tight viewing regulation, to many visitors, the story that they have looked at the Mona Lisa in person might still be more important than actually seeing the painting. Then, what can be a better thing to do for social media than taking a photo of the Mona Lisa with their phones?

Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

One factor that has inevitably induced the invisibility of these masterpieces is their iconification, and then the wide appropriation of these icons, a process analyzed in media study by scholars like Robert Hariman, John Louis Lucaites, and Mette Mortensen. Mortensen argues that these artworks are constructed as icons in public discourses through intense circulation across media platforms along with repeated statements about their iconic status and ability to symbolize master art or art of an era. Icons travel faster and farther. When circulated in the transnational and transtemporal media circuit, meanings are lost and found in translation between contexts. Furthermore, appropriations, which inevitably lead to mistranslation, are central to both the production and reception of icons. The Mona Lisa not only appears in art books, art exhibitions, and art news but also on Louis Vuitton bags and within thousands of memes over the internet. In appropriations like these, the Mona Lisa is taken out of its context; then, what it represents takes over what it is. Hereby, famous paintings like the Mona Lisa become tropes to the point people no longer feel the need to take a real look at it to know what it is. In the same basket are paintings like Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night, Claude Monet’s Water Lilies, Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans, and Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog.

Photograph from Beyond Van Gogh immersive exhibition, pictured in Miami. Credit: Photo courtesy of Gayaman Visual Studio.

Although overexposure and appropriation result in the blur of the original, they sometimes can introduce a critical-reflexive dimension to iconic art and its reception. Appropriation of ready-made images and artifacts has had a significant presence in modern and postmodern art in the west. From the early 20th-century avant-garde practices such as collage, photomontage and, especially, the ready-made, to the Pop Art movement in the 1960s and photography during the late 1970s and early 1980s, various strategies of appropriation was critically deployed to examine the concept of originality or to critique structures of representation and new visual languages within the US or the western art world.

However, since the 1980s, simply due to the augmentation of appropriation in art, this strategy gradually became a normalized approach that has lost some of its original radicalness and criticality. In Douglas Crimp’s “Appropriating Appropriation (1982)”, he compares the act of appropriation in the works of Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince to that of Sherrie Levine and argues that Sherman and Prince made work according to the institutional discourse of appropriation and no longer break social norms or add to the discourse like what Duchamp and Levine have done. “And in this way, the strategy of appropriation becomes just another academic category through which the museum organizes its objects.” Appropriation as this very specific act of artmaking is only a digression from what we previously see in the case of the Mona Lisa. What is really at root is overexposure and within, some inappropriate appropriations. But what is so hilarious and ironic here in this art historical talk is that even appropriation itself can be buried under its overuse.

Richard Prince / Untitled (cowboy). Image credit to the MET.

Cindy Sherman / Untitled Film Still #21. Image credit to MoMA.

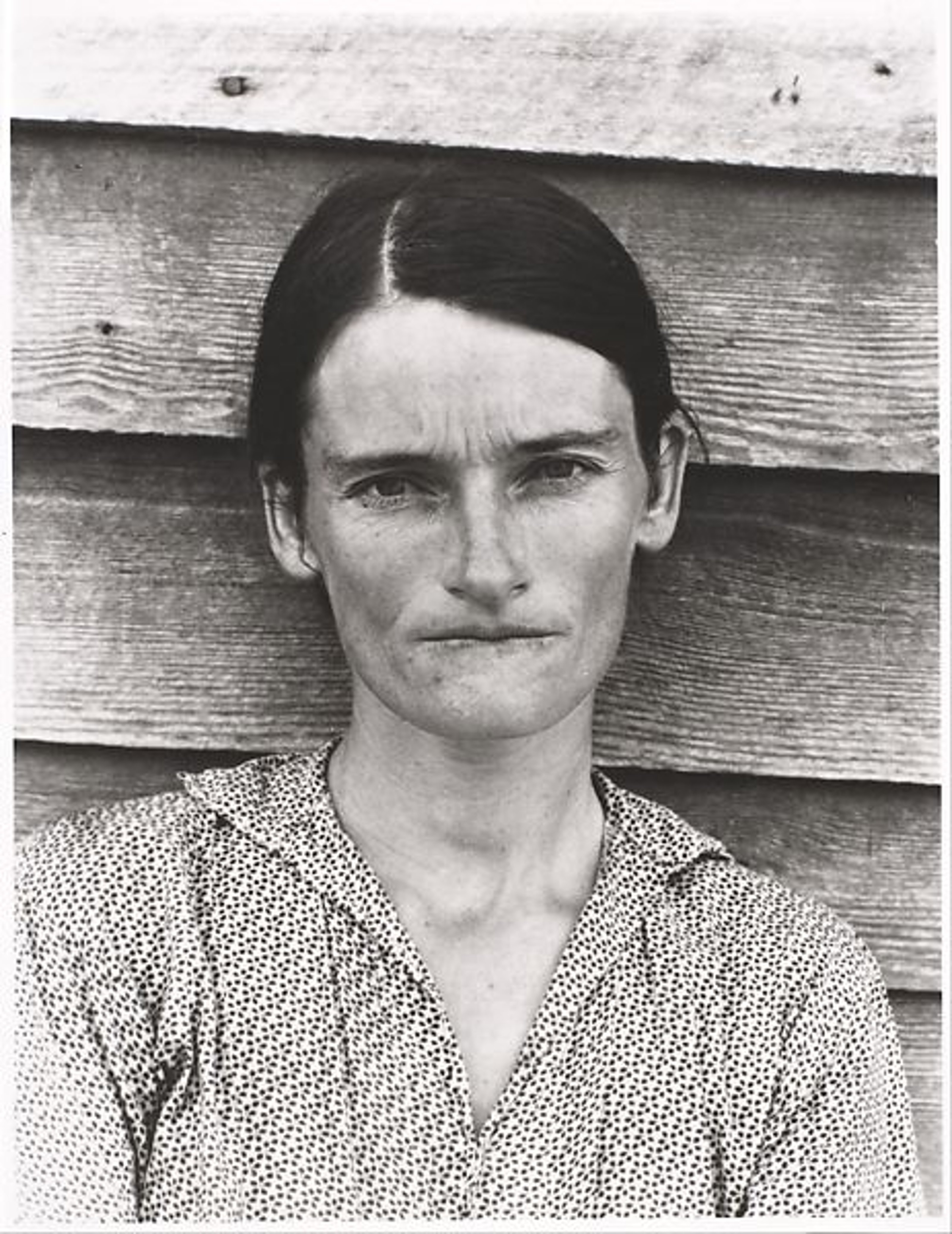

Sherrie Levine/ After Walker Evans: 4. Image credit to the MET.

And of course, the globalized, modernized, decentralized, speedy, and image-driven mass media and social media of today only exacerbate the iconization, appropriation, and then trivialization of icons, things that are intentionally or sometimes just magically labeled as important. For artists like Jeff Koons and Andy Warhols, when their works gained global recognition and much profit through countless legal and illegal reproductions, the criticality of their works as art is replaced by the ubiquity of capitalist products. However, at the end of the day, it is as hard to evaluate whether one fate or the other is better for artwork as to argue for the best way people should interact with the artwork. One is arguably just as valid as the next. But we can reasonably speculate that the over-saturation of images, the overload of information of this era have already changed the way people look at art. For better or for worse, we don’t know.

Kathryn Andrews’s course on The Death of Looking – Artist as Brand offers a multidimensional exploration of the phenomenon when a similar process of iconification happens to artists rather than a painting. To learn more about how recognition impacts the very act of looking and how artists have resisted such an effect, enroll now in Kathryn Andrews’s The Death of L****ooking – Artist as Brand.