This chapter is a decolonial initiative that critically engages with the representation of the Palestine question in general and Gaza refugees in particular by British Pathé, which, as a leading media institution of the British Empire, was also a dedicated advocate of Zionist ambitions and Jewish settlement in Mandate Palestine. I interrogate Pathé's discursive strategies in representing the 1947–48 Nakba, the 1956–57 Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip, and Israel's subsequent occupation of Gaza beginning in 1967. Highlighting strategies of inclusion and exclusion, deconstructing a one-sided historical narrative written by the victor, and contextualizing that narrative in the suppressed past of the subaltern, I argue that British Pathé provided a consolidating, hegemonic discourse on Palestine-Israel that prevails to this day in mainstream political, media, and academic discourse.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, photography and the moving image became tools of European hegemony, imperialism, and colonialism.1 Orientalism, a discourse established through centuries of imaginative representations in literature, art, visual media, film, and travel writing, proclaimed "the technological and hence civilizational superiority of the West."2 Orientalism is thus a method of domination that constructs the colonial gaze: "The optical unconscious of early cinema is also the optical unconscious of colonialism, insofar as the gaze is a mechanism of dividing and conquering, of preserving and possessing."3 Essentially, the multifaceted Orientalist discourse differentiated between colonizers and colonized, "advanced" and "backward" races, to rationalize European exploitation of peoples around the world.4

In nineteenth-century Europe, indigenous Palestinians were portrayed somewhat differently than other colonized subjects: not only as primitive but also as rootless "wanderers" in the desert, which undermined their claims to their ancestral lands and facilitated their displacement and replacement with a new population supposedly "returning" to its historical land.5 A dogmatic textual reading of the Bible led to a "Peaceful Crusade" of European travel to Palestine. "Countless expeditions" arrived in Palestine, including European consuls, missionaries, artists, archaeologists, and pioneer photographers who wished to use "the realism of photography" to memorialize biblical sites and prove the Bible's literal veracity amid a rising conflict between faith and science over Charles Darwin's theories.6 Although this did not (yet) include territorial domination, the crusade served as an "effective takeover of the Holy Land", producing a mass of literature on Palestine that outweighed that on any other non-European territory. Meanwhile, the Great Powers' "Eastern Question", supported by nongovernmental political, social, and religious movements and organizations, "often turned into aggressive demands for European occupation and rule of Palestine."7

During this period, Palestine was also constructed as a "chosen land" for the Jewish people.8 Religious associations and supremacist cultural and political attitudes toward Arabs visually represented Palestine as unchanged since Christ’s day 9 and requiring "redemption," through the "restoration of Jews" and the elimination of the indigenous Palestinians who were viewed as "a source of contamination."10 Evangelical Christian Zionism thus lay the foundations for the Zionist Jewish state as later conceptualized by Theodor Herzl in his 1896 pamphlet The Jewish State.11 These views accorded with those underpinning British colonial expansion across the non-European world. More than a century later, the State of Israel and supporters of Zionism, Christian and Jewish, continue to claim the Bible as a "mandate" or real estate deed for the "Jewish people"12, in ways that distract from the consequences of these views on Palestinian natives.

Artwork: David Roberts / Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, 1839. Cleveland Museum of Art.

If "all rulers are the heirs of prior conquerors", as stated by Walter Benjamin13, Israel is an heir of the British Empire. Colonial history has until recent decades been written overwhelmingly from the victor's viewpoint, with little regard for a colonized subject's "permission to narrate."14 Politicians and policy makers, knowledge producers and media platforms, participate to this day in the victor's "triumphal procession", both actively and by adhering to the victor's version of history, regardless of its implications for the colonized.15 The digitized archive of British Pathé, which continually championed British colonialism, offers an example of such topdown history.

Historical objects, however, can provide "a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past" and "blast a specific era out of the homogenous course of history."16 The past can only speak through its archive, but remediation or "reconstruction work" adds new meaning through archival material's renewed circulation.17 As Dagmar Brunow argues for Pathé's coverage of the Windrush migrants in Britain, a critical engagement with the archive can reclaim the legacy of Black immigrants and open new possibilities for shared understandings.18 A decolonial critique of British Pathé's discourse on Palestine not only deconstructs its one-sided historical narrative "based on referentiality, realism and facts that represses heterogeneity"19 but also contextualizes it in the suppressed past of the dispossessed Palestinians. By highlighting the strategies of inclusion and exclusion of Gaza in the newsreels and by deconstructing a one-sided historical narrative from the victor's viewpoint, I argue that British Pathé provides an example of the consolidating hegemonic Orientalist discourse on Palestine-Israel that prevails to this day in mainstream political, media, and academic discourse.

Soon after the advent of the moving image, films of Palestine were increasingly seen as a "big business", and Western media companies raced to send cameramen to bring home "real" films of life in the Holy Land.20 British Pathé was among the first in the race. In 1910, Frenchman Charles Pathé introduced the new medium of the newsreel to British audiences, establishing a regular weekly newsreel "which for the first time in the history of communication, delivered news coverage to a distribution network worldwide."21 British Pathé and its rival British Movietone were the only reel companies to survive until the 1970s, when television spelled their demise.22 Until then, Pathé "was at the forefront of cinematic journalism, blending information with entertainment to popular effect."23 Particularly after the advent of sound in the late 1920s, the company's short expository newsreels consisted of well-constructed and well-presented film, combining sound, dramatic music, and a "voice-of-god" narration in which a "typically male, authoritative, and didactic" speaker is heard but never seen, with supportive images.24 Newsreels became a prominent feature of the British cinema experience, and their impact on big screens during the first two decades of talking film should not be underestimated.25 Their simple structure, together with their adherence to the government's line and prevailing cultural attitudes, condensed discourses and created generic, simplistic, and problematic racial and gendered stereotypes.26

British Pathé frequently departed from daily life in Britain to bring its audiences images of faraway "exotic" lands and people. In so doing, Pathé's discourse functioned firmly under the auspices of the British Empire. As the documentary Around the World: The Story of British Pathé27 suggests, the anthropological value of its international filmmaking cannot be assessed without considering its ideological relationship to British imperial ambitions, and particularly the projected inferiority of "Others", often associated with British attitudes of racial superiority. A 1926 essay by the editor in chief of Pathé News, Emanuel Cohen, expressed this ideology unapologetically: "Pathé News is now world wide, its tentacles reaching into every nook and corner of the Earth—civilized and uncivilized—its thousands of lenses focused on every political development, witnessing the pageantry and the tragedy of every people; peering into the customs of every land; holding a mirror to every phase of human activity everywhere."28

In reporting Jewish settlement in Mandate Palestine in the 1930s and 1940s, Pathé presented a "strong pro-Zionist stance", in accordance with its regard of "Palestine as the most logical solution for Jewish refugees."29 Szczetnikowicz’s research foregrounds the representations of Zionist settlers in Palestine, but to date no one has examined the marginalization of the Palestinians in Pathé newsreels. Pathé presented a one-sided representation of Palestine, a celebratory story of British-enabled Zionist achievements that repressed and misrepresented the anti-colonial struggle of the Palestinian people. The portrayal of the Palestinian Arabs in British and American newsreels and documentaries in the 1930s and 1940s, including by Pathé, "was diametrically opposed to the image presented of the Zionist Jew."30 Therefore, "the very positive and extensive representation of Zionism and its objectives" was echoed in "the denigration of the native Palestinian", reproducing a racialized "stereotype of the Arab as a backward, hostile and barbaric peasant."31 Western spectators consequently viewed Zionist settlers as deserving members of the Western civilization with whom Europeans could identify, and Palestinian natives as undeserving. Jews themselves had, of course, been subjugated to centuries of anti-Semitic tropes in the West, where they were portrayed as "somehow less human and counting for less than the White Man."32 However, this changed beginning in the 1920s with leading Zionist organizations, such as the Jewish National Fund, appropriating documentary films to demonize the Palestinian natives and glorify European Zionist settlers, and to invite international sympathy, funds, and recruits for the Zionist project.33

British Pathé's bias not only was a result of the imperialist "culture of the time" but also was part of an effort to cultivate public consensus toward British complicity in aiding the Zionist project at the expense of Palestine's indigenous population, whose mass dispossession and expulsion went largely unnoticed in 1948. Nevertheless, shifts in representation occurred in response to the specific political challenges that British imperialism confronted. In this chapter, I examine these shifts in Pathé newsreels, focusing on their representation of the Gaza Strip and unpacking how Orientalist ideology manifested in different historical moments.34 I interrogate the discourse of Pathé reels, focusing on the Nakba of 1948, the Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip during the Suez Crisis of October 1956 until early 1957; and Israel’s subsequent occupation of Gaza in 1967. I discuss not only those reels that made it onto cinema screens but also those that were never screened and have only recently been made available through the British Pathé Unissued archive.

Between 1947 and 1949, British Pathé produced 146 reels on Palestine. Much of this material was unissued or reported on diplomatic matters, but the large number indicates the seriousness of this catastrophic period. Pathé's reporting on Palestine and the Western media more generally exhibited a "deep chasm between the reality and the representation."35 Predicated on an imperial campaign of misinformation over the previous decades that celebrated Zionism and denigrated Arabs, the media discourse rationalized the horrific outcome of the Palestinian Nakba.

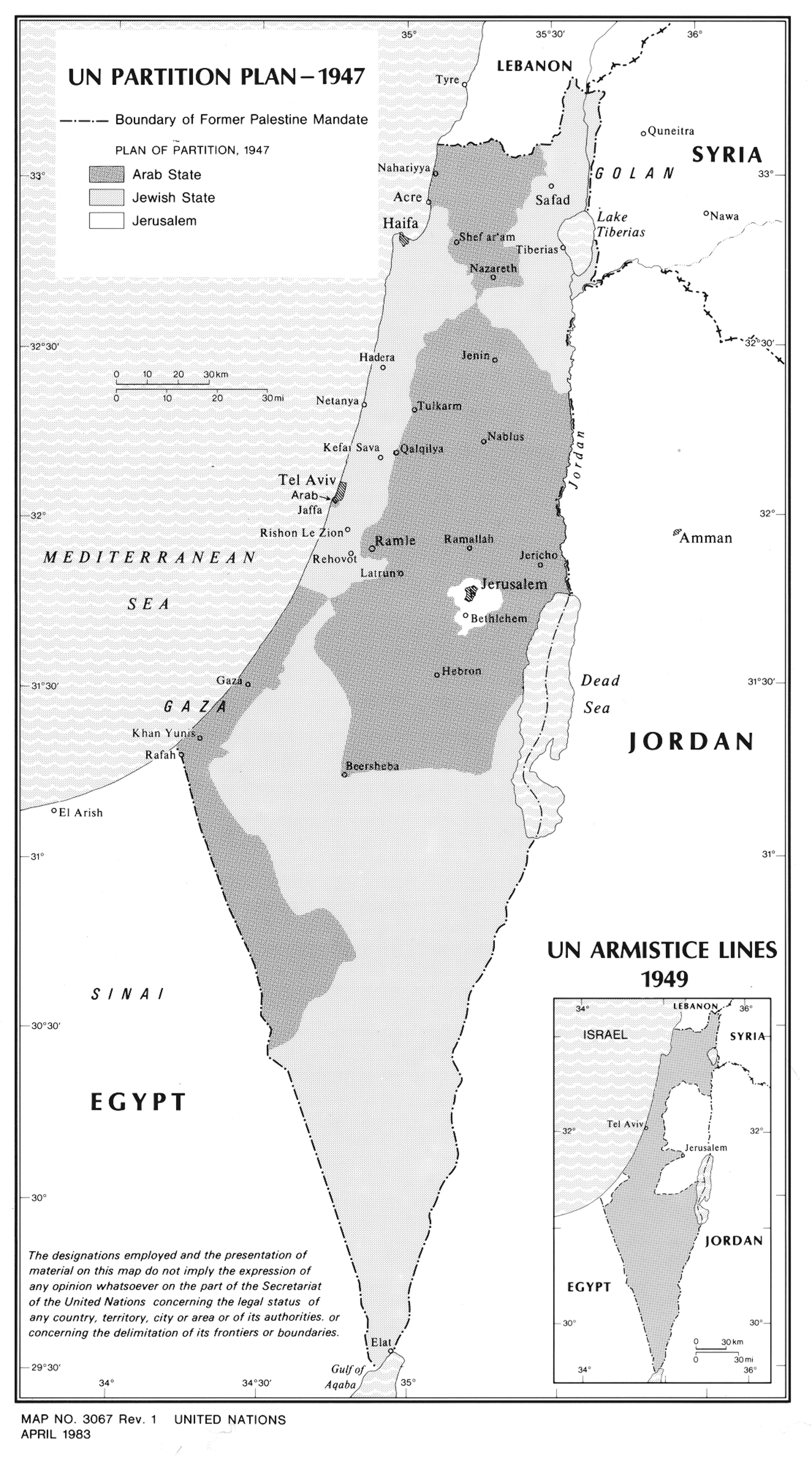

In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly voted to partition Palestine between a Jewish state for the minority settler population and a smaller Arab state for the indigenous Palestinian majority.36 Partition paved the way for the implementation of a Zionist apartheid separating Jews from non-Jews.37 The UN partition and clashes between Zionists and local Palestinian militias provided "the perfect context and pretext" for the implementation of a carefully thought out "large-scale intimidation", code-named Plan D. This plan included Zionist militias "laying siege to and bombarding villages and population centers; setting fire to homes, properties, and goods; expelling residents; demolishing homes; and, finally, planting mines in the rubble to prevent the expelled inhabitants from returning."38 This campaign accelerated after Britain's withdrawal on May 14, 1948.

United Nations Partition Plan. Publication date: November 29, 1947.

By the end of 1949, Israel ruled more than 77 percent of Palestine.39 Two-thirds of Palestine's indigenous people were dispossessed and displaced, a process that continues today, making Palestinian refugees the most long-standing refugee population worldwide.40 Far from being "a miracle", as Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, described the situation in early 1949, this "miraculous clearing of the land" was the result of deliberate ethnic cleansing.41 Although it was witnessed by UN observers and international reporters, the 1947–49 ethnic cleansing of Palestine remains "systematically denied, not even recognized as historical fact, let alone acknowledged as a crime that needs to be confronted, politically as well as morally."42 The rhetoric of the Pathé newsreels contributed to this denial.

In The Arabs Declare Holy War (1947), Pathé predicted a "transfer of power" in Palestine in its coverage of the UN vote, painting a picture of an internationally recognized resolution for two states in Palestine welcomed by Jews but rejected by Arabs. This development was expressed in simple and exclusively Zionist terms. The commentator describes partition as an "uneasy compromise." Against an illustration of the plan, he says, "The Jewish state will include the ports of Haifa and Tel Aviv and the whole of the Negev Valley", and "The Arabs will occupy the fertile eastern part", concealing the fact that the lesser portion was given to the native majority, and portraying the Palestinians as ungrateful for receiving the "fertile eastern part" of their homeland. Jewish crowds are depicted celebrating the decision, while the narrator says, "First reaction from the Jews was one of joy; crowds gathered in the streets and greeted the birth of their state with traditional dances." From a low angle, the spectator looks up to Zionist Jews, who seem victorious and heroic. Zionists were joined by British troops as seen in figure 10.1, all under the future Israeli flag, reflecting the kinship between the soldiers of the British Empire and the European settlers of the Zionist project, even at a time of significant tension between Britain and the Zionist movement.

Still showing British troops among a group with the Zionist flag celebrating the UN partition resolution from The Arabs Declare Holy War (1947). Image supplied by British Pathé.

Ignoring the violence committed against Palestinians that had already begun, the narrator states that "Arab opposition to the partition scheme has been violent." Against shots of Egyptian soldiers in uniform, the narrator claims that "the call for a holy war against the Jews went out from Cairo." The inaccurate framing of the Palestinian anti-colonial struggle and Arab support for it in exclusively religious terms ignores the realities of the settlerindigenous conflict, the involvement of Christians in the Palestinian national movement, and the harmonious relations between Palestinian Arabs and Jews before Zionism. Moreover, labeling the Arab opposition to the colonization of Palestine as "a holy war against the Jews" would seem particularly abhorrent to European audiences in the immediate wake of Nazism.

"As in India", the Pathé commentator continues, "transfer of power in Palestine will bring bloodshed." The analogy between Palestine and the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan overlooks a major distinction. While power was transferred to local leaders in India and Pakistan, in a process that was troubled by divisions born out of British colonialism and partition plans that accentuated religious difference, the ensuing bloodshed in Palestine was a result of the transfer of power from Britain to another colonial power. Pathé's framing of partition in both India and Palestine also absolved Britain of responsibility for bloodshed in both places, depicted as an unfortunate by-product of a religious divide rather than a legacy of British rule. Against a wide shot of Egyptian soldiers marching behind the Palestinian flag, the reel leaves spectators with the words: "For the Holy Land, the immediate future will not bring peace." Although it would be Zionist military forces who expelled hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homeland at gunpoint, the finger is pointed at the Arabs for the predicted violence. Pathé's coverage thus conceals how the UN partition was the "opportune moment" that Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, wished for in a 1937 letter for turning the long-standing Zionist vision of an exclusively Jewish Palestine into reality.43

Pathé released The Drama of Palestine on January 12, 1948, the first newsreel after the Zionist campaign of ethnic cleansing had begun. A "wellorchestrated campaign of threats" involved special units of the Zionist militia, the Hagenah, entering "defenseless" Palestinian villages and warning locals against cooperating with the Arab Liberation Army.44 “Any resistance to such an incursion", Pappé writes, "usually ended with the Jewish troops firing at random and killing several villagers."45 Dayr Ayyub, a village of five hundred inhabitants near the city of Ramla, and Bayt 'Affa, a village in the Gaza subdistrict, were the first two villages to fall victim to "this terrorist method."46 Both villages resisted, and while Dayr Ayyub was completely destroyed and depopulated after repeated attacks by paramilitary Zionist groups in April 1948, Bayt 'Affa first successfully repelled the raiders before meeting the same fate by the summer.47 More crimes were committed by the Hagenah's elite force, the Palmach, and the right-wing Revisionist Zionist groups, the Irgun and Stern Gang, against Arab neighborhoods of Haifa, Jaffa, and Jerusalem amid "a gradual but obvious British withdrawal from any responsibility for law and order."48

The very title of Pathé’s coverage of these events reduces the Zionist campaign of dispossession, dispersion, and bloodshed to a "drama." Beginning with footage of destruction without explaining whose buildings or homes are being destroyed, the narrator says: "Against a background which daily gains resemblance to war-scarred Europe, Palestine now grips with almost unrestricted racial warfare." The question of who had the upper hand remained concealed, but after decades of propaganda produced by Pathé and other Western media outlets, the Western spectator was left with sympathy only for the Zionists. Against more shots of people among the rubble and British troops attempting to help, the commentator pins the blame on "the lawless element of Jew and Arab populations", bemoaning that they have "take[n] over from the servants of the policies of law and order"— again exonerating the British of any responsibility for the strife.

Over a group of Zionist fighters preparing armored cars, the commentary paints a picture of a war between two equal sides, consolidating a discourse that still characterizes news reporting today: "In the backstreets of Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Jaffa, the thugs of both sides build up armored cars for war against each other." This is followed by shots of people queuing for an id check, as the commentary proceeds: "In between them, victims of the struggle, stand a great majority of simple people of both sides." Adhering to normative Orientalist tropes and decontextualizing the reality of Zionist settler colonialism, Pathé’s The Drama of Palestine ultimately legitimates the injustice of Israel’s foundation atop ethnically cleansed Palestine.

Less than a month later, a similarly constructed forty-six-second reel, Palestine’s Fleet Street Gutted, covers more violence in Jerusalem. Unnamed "terrorists" had set fire to "the offices of the Palestine Post", killing one and injuring twenty, the narrator reports as images of the arson are screened. "Yet this is but a small incident in troubled Palestine", the commentator continues, announcing that daily reports of more killings arrive: "British, Arab, and Jewish lives are lost." The reel ends by reassuring audiences that "May the 15th is the date set for the end of the Mandate."

Personalized shot of a British soldier being saluted by General Alan Cunningham before leaving Palestine, from Palestine Defies Solution (1948). Image supplied by British Pathé.

On May 27, 1948, another reel was released, entitled Palestine Defies Solution. It appears to be an excerpt from Palestine Story, a longer unissued newsreel covering the departure of the British high commissioner for Palestine and Israel's Proclamation of Independence. It begins with dramatic music as the voice-over declares, "The Palestine Mandate has ended; Britain is relieved of a burden." A British guard of honor presents arms at the Haifa quayside, as General Alan Gordon Cunningham salutes British troops "who showed exemplary patience for a thankless task", inviting the thanks of the audiences. A close-up of a British soldier presents the troops in a heroic light, harmoniously with previous representations of British military.

The reel evokes the familiar pro-Zionist stance of Pathé films of previous decades. Spectators see European-looking Jewish settlers joyfully disembarking from ships at Haifa port, as the narrator says, "With the end of the mandatory power, all legal bars to immigration are removed." With a familiar Christian Zionist ring, he continues, "The sea is now open to the seekers of the promised land." These "seekers" are depicted in personalized shots as they land "in a country already in the grip of a bitter racial strife." This framing evokes a continued danger facing early Israelis, inviting a sympathetic concern from British audiences whose affinity with European Zionists had already been consolidated.

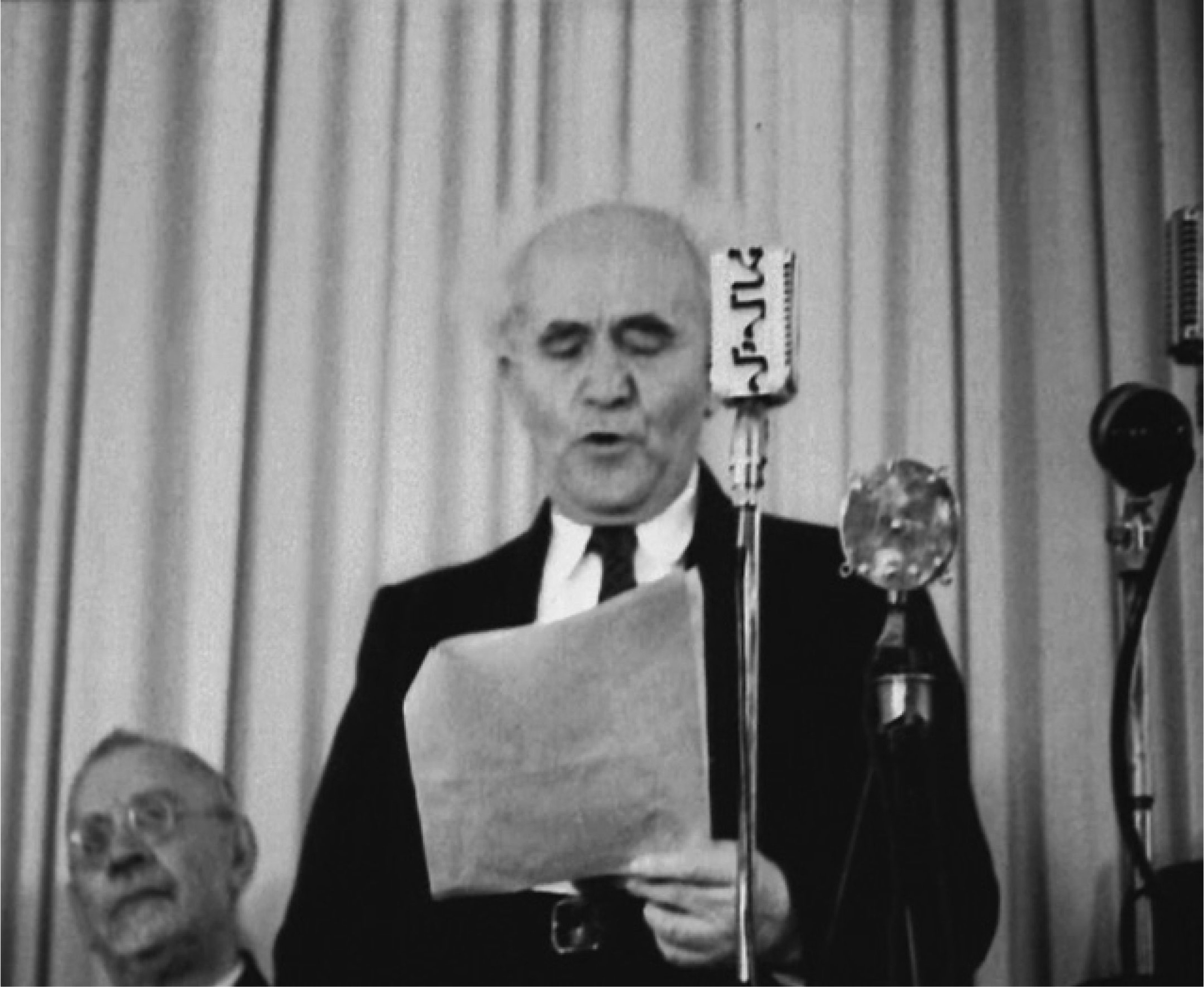

David Ben Gurion reading Israel’s Proclamation of Independence on May 15, 1948, from Palestine Defies Solution. Image supplied by British Pathé.

The footage shifts to bombed-out buildings against mournful music yet provides no information as to what happened to the dwellers of what appear to be traditional Palestinian homes. The music is interrupted by the rejoicing of crowds in Tel Aviv welcoming Ben Gurion, who victoriously arrives "to read the proclamation of the new nation: The State of Israel." The "triumphal procession" is depicted in a pan shot following Ben Gurion as he salutes the crowds, reinforcing the image of the Zionists as heroic victors.

There follows footage of settlers digging trenches around a new colony, rifles slung on their backs: "Born in the throes of war, with undefined frontiers, facing Arab opposition, the new state precipitates a world problem." The image of the self-made heroic and modern Zionist is further reasserted by women working in a vegetable garden and a close-up of a pistol holstered around a woman's waist. The commentary proceeds: "The tillers of its fields go on, while the world's United Nations engage in futile talks", presenting Zionists as the protectors and cultivators of the promised land. The Palestinian peasantry had once been the tillers of Palestine's fields, but now, away from Pathé's cameras, they were being pushed into refugee camps.

The reel then shows a dead horse and a wrecked bus as the narrator asserts, "Tel Aviv comes under Egyptian aerial bombardment." Pathé uses this attack as an opportunity to reinforce an Orientalist juxtaposition between Arabs and Jews by claiming that Tel Aviv "feels like the type of civilization from which the Jews fled [Europe], and which the Arabs seek to keep from their shores." This falsely paints the conflict as a "clash of civilizations." It also erases the Arab modernity already present in Palestinian cities, especially Jaffa, adjacent to Tel Aviv, where ethnic cleansing was underway.

The reel ends with King Abdullah of Transjordan, Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia, and King Farouk of Egypt talking and walking together toward the camera, the narrator proclaiming that they "unite the Arab world against the Jewish state", thus presenting Israel as the underdog opposing Arab hostility from all sides. In fact, "the neighboring Arab states sent a small army" once the British had departed, while the Zionists' ethnic cleansing of Palestine had already begun more than a month earlier and Arab forces could do nothing to prevent this campaign.49

In the newsreel Britain Recognises Israel (1949), Pathé references the specter of the Cold War and the West's desire to pull Israel into its own orbit. This was not arbitrary, but an expression of the proxy war enacted in the Middle East militarily and ideologically, with Palestine at its heart. The narrator says: "With the new state now acknowledged by the majority of the United Nations, Israel's first general elections became a matter of some importance. The voting would show whether this vital Middle Eastern area would swing left and therefore to Russia, or whether it would follow President Weizmann’s decision to align itself with those in the Western world." Weizmann appears smiling alongside his wife, as the commentator applauds his alignment with Western ideology. Between the competing value systems, however, lay a dispossessed people, whose story remained untold.

After 1945, ideological and political domination over emerging formerly colonized states lay at the heart of Britain’s vision for the "Third World."50 Pathé sought to justify the colonial endeavor in the former colonies by constructing representations, as Ramamurthy argues, enacted through "modernization theory", which came to underpin neocolonial exploitation.51 In the 1950s, Pathé’s films of African nations "show a shift from an Africa of wild animals and raw materials to an Africa with modernist-style buildings, developing cities and vast hydroelectric schemes."52 These images influenced audiences' understanding of Britain's international role as one of benevolently enabling its former colonies to move toward self-rule.

This vision played out differently in colonized Palestine. While Palestinians were denied self-rule, Pathé consistently depicted Zionist Jews, enabled by the British, as the pioneers of modernism and innovation in newsreels produced during the Suez Crisis of 1956, which resulted in Israel's first occupation of Gaza.

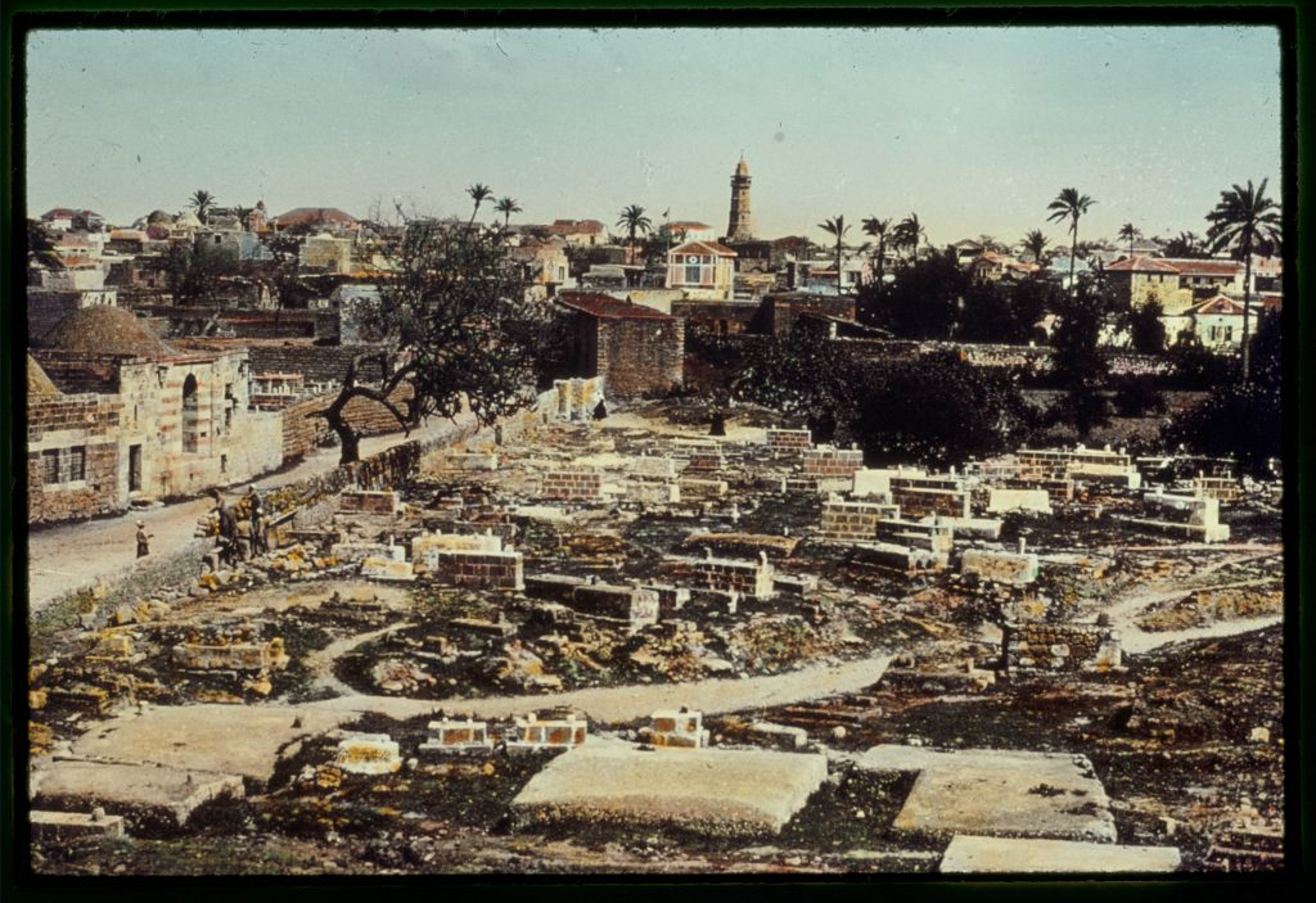

Gaza rarely featured in Pathé newsreels until the mid-1950s, primarily because Pathé's overwhelming focus was on the Zionist settler community, which was limited in the wider Gaza area before 1948. The camera's preference for the settler society created by the Jewish immigrants led to the absence of Gaza from the screen. Travelers and writers have noted for centuries Gaza's prosperity, fertility, vegetation diversity, pleasant weather, and resource-rich nature.53 Before 1948, the Gaza district was thirty-eight times its size today, the largest district of mandatory Palestine, encompassing around ninety villages and towns.54 With growing urban spaces, cultural centers, and thriving fish, agricultural, and tourism industries, Gaza had qualities that challenge Western associations of development and modernity in Palestine with Zionism. Recently recovered photographs from Kegham Djeghalian, a Palestinian Armenian who opened his studio in Gaza in the 1940s, testify to the vibrant life enjoyed by Gaza residents that is marginalized by Pathé.55

Australian Surf Men—In Palestine, issued in 1942, focuses on some of the more than 100,000 Australian soldiers who were stationed in Palestine during World War II. The reel shows soldiers surfing on Gaza’s beach, the narration celebrating how "for one glorious day, they paused in the ugly business of battle and turned Palestine's beach of Gaza into a second Bondi." Seemingly heroic Australian "fighting men" experience "pleasure from one day of homely relaxation," while Australian women nurses silently watch from a tent, as the commentator proclaims that they "are home again in imagination." Pathé constructs a narrative dominated by the celebration of war and masculinity performed in the practice of surfing, long part of white settler colonial culture in Australia56, now transported to Palestine's shores.

Djeghalian’s favourite photo by his grandfather shows two children walking along Gaza’s beach. They are perhaps five or six years old—his aunt and his father. In the foreground, one sees the photographer’s shadow, like a guardian angel. Image source: Hadara Magazine. Courtesy of Kegham Djeghalian.

No Gazan locals appear in this newsreel. However, they do appear in an unissued 1940 reel entitled Australians in Palestine. Despite the reel's focus on Australian soldiers, and their interaction with then British foreign secretary Anthony Eden during his visit to Egypt, a substantial segment of the nine-minute reel depicts Palestinians in Gaza, including a spaciouslooking Palestinian village with houses made of mud and straw. These images challenge the hostile Orientalist representation of Arab Palestinian society found in Pathé's other productions. The Australian soldiers buy oranges and interact with groups of Palestinians in a friendly manner. Three generations of Palestinian women enjoy the outdoor sun, wearing traditional jewelry and embroidered dresses. We also see elderly men sitting on the ground, and women balancing clay pots on their heads.

It is unclear why such pictures were never screened by Pathé, but the Great Revolt had ended only a year before; the footage of the relaxed and hospitable Gazans contrasts starkly with the image of Palestinians as violent and backward that had been presented by Pathé's reels until that point. After the 1939 white paper, which Britain issued to end the Palestinian Great Revolt and which imposed restrictions on Jewish immigration, the British government "was preparing audiences for a change in attitudes towards Jews as deserving 'settlers' who had to be protected from the Arab 'terrorists'."57 In this context, these Palestinian scenes could indicate an anthropological interest on the part of the cameraman in the Palestinian way of life, but their exclusion from screening is harmonious with Pathé's prejudices and Britain's policies.

Gaza was transformed by the events of the Nakba. With the destruction of hundreds of villages and the depopulation of Palestinian cities, approximately 200,000 refugees (compared with Gaza’s pre-1948 population of 80,000) were forced into the narrow stretch of land that came to be known as the Gaza Strip.58 In the absence of an Arab Palestinian state, the Gaza Strip came under Egyptian occupation. Gaza's indigenous economy collapsed as a result of the sudden influx of refugees and the widespread Zionist domination of its agricultural land and ports.59

Although Egypt contributed extensively to the relief of Gaza refugees in the immediate aftermath of the war, it soon imposed oppressive practices.60 In the early 1950s, Egyptian policies focused on centralizing power in the military administation of the strip and high administrative positions in other areas, including legal systems, health, education, and commerce. Palestinian refugees and indigenous Gazans were marginalized in all public sectors and carefully monitored to restrict their political organizing.61

The story of Gaza's refugees, who were forced to rely on humanitarian aid from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for their survival, was ignored by Pathé. Meanwhile, it produced such celebratory reels as Israel, the first in color to depict "infant Israel." The state founded on Palestinian dispossession was depicted as "a young, vigorous nation", its dreams shaped by immigrants arriving in increasing numbers to what the narrator still deemed "the promised land", to "reclaim a neglected land." Zionism, as a form of settler colonialism, had sought the "elimination of the native"62; Pathé continued to assist this mission by airbrushing the native Palestinians from the glossy picture of life in Israel. For example, an Israeli unit led by Ariel Sharon launched an attack on the al-Burayj refugee camp in central Gaza that killed at least fifty Palestinians in August 1953, one massacre among many that went unreported by Pathé or any other British newsreel.63

The latter half of the decade was marked by more violence. The Pathé archive contains twenty-four newsreels from 1955 to 1957 tagged "Gaza", most of which revolved around the tension between Israel and Egypt; only nine were screened in cinemas. Egypt-Israel Border Clash, screened in March 1955, makes a spectacle of Operation Black Arrow, which was ordered on February 28 in response to Egypt’s alleged support for Palestinian resistance activity and which resulted in the killing of tens of Egyptian soldiers. Israeli historian Avi Shlaim attributes this "devastating raid", which occurred after four months of "comparative tranquility along the border", to the desire of Ben Gurion, recently emerged from retirement, to "dramatize his return to power", assuage the Israeli public’s anti-Arab sentiments, and "cut… down to size" Egypt’s Arab nationalist president, Gamal Abdel Nasser.64

While Palestinians were otherwise marginalized, an image of Palestinian children is presented as the narrator describes "a group of Palestinian refugees look[ing] at the burning remains of a UN store [of humanitarian supplies] set fire", portraying the incident as "collateral damage." The reel presents Israel’s version of events, claiming that "Egyptians attacked one of their patrols", and "the fighting continued into Egyptian territories." The reel shows "a lorry riddled with bullet holes said to have been carrying some of the thirty-eight Egyptians killed", and ends with protests by both Israel and Egypt to the UN. The commentary preoccupies spectators with this diplomatic narrative, while the stateless Palestinians at the center of the "clash" are presented in a single scene of Palestinian children passively observing events.

However, Palestinian refugees in Gaza did not simply watch from the sidelines as Egypt and Israel squabbled. Post-Nakba Gaza was a site of great political dynamism despite Egyptian measures to restrict Gaza residents' political activities.65 The Communist Party and the Muslim Brotherhood, both underground political movements at the time, provided the wells of political activism inside the strip and were strongly supported by the refugees. The UN's failure to implement Resolution 194, which called for the return of the refugees to their homes, the humiliation of dependency on humanitarian aid and the vulnerability to Israeli violence inspired resistance. For example, when Nasser, wishing to avoid a potentially explosive situation in the Gaza Strip and war with Israel, considered a 1954 US-UNRWA plan to resettle the refugees in the Sinai Peninsula, refugee-led demonstrations and riots in the Gaza Strip targeted Egyptian government buildings for two days, forcing Nasser to discard the plan.66

Southern Palestine, Hebron, Beersheba and Gaza area. Gaza. Judges 16:1. Photography: Matson Photo Service. Published between 1950 and 1977.

Regional conflict soon put Gaza at the center of drastic events. The Suez Crisis was triggered by Egypt's nationalization of the Suez Canal in July 1956. Nasser's actions and increasing power concerned both Western neocolonial leaders and the Israeli government. To many in the Arab world, his leadership came to represent the cause of Arab emancipation from Western hegemony. His sponsorship of a resolution at the 1955 Bandung African-Asian Conference calling for the repatriation of Palestinian refugees was seen as a particular threat by Israel.

Gaza Clash (1956) revolves around UN secretary-general Dag Hammerskjöld's visit to the Gaza Strip and focuses on an Israeli settlement that had "suffered" an attack by fedayeen (resistance fighters), killing an Israeli sergeant. After depicting military funeral processions and an Israeli child, the reel concludes with the eagerness of the UN and "world opinion" for "an answer to the threat to the peace of the world"—implicating Egypt and Nasser’s revolutionary leadership as "the threat." Once again, the story of Gaza's Palestinian residents, mostly refugees, goes untold and without a human face. The focus on the funeral processions of the Israeli sergeant, and the omission of the violence committed by the occupying power present Palestinian resistance as "irrational" acts of terror and Israelis as the victims who deserve viewers' sympathy.

Another short reel, Selected Originals—Gaza Clash aka Funeral of Israel Sergeant (1956), shows Ben Gurion helping to erect “barbed wire on the Gaza Strip, part of his country’s emergency frontier fortifications, as tension rises in the Middle East.” Concluding on the Israeli premier’s declaration that Israel “will not start a war”—a claim that was soon to be proved false— Pathé exonerates any future conflict involving Israel as an act of necessary self-defense.

In fact, Israel prepared for a "preventative" strike against Egypt in October 1956, providing a pretext for Britain and France to join forces in the name of protecting "Europe's future status."67 Rather than seeking a peaceful political settlement over the Suez Canal, as proposed by the United States, which was then coming to challenge the hegemony of the old European empires in the region, Britain and France opted for military intervention to overthrow the government of Nasser, whom they smeared as a "new Hitler" to justify their acts. Pathé provided its spin on these events in Israel Invades Egypt—Britain Acts. Presenting the British-led attack on Egypt as necessary to stop Nasser and maintain Israel's survival and Western domination over the canal, the reel stoked Cold War fears by warning that Egypt had "turned eastward"—that is, to the Soviets—"for her supplies of arms." Despite opposition to military action by the UN and the United States, British prime minister Eden rationalized his actions in a television and radio broadcast that was also screened by British Pathé in a reel titled, Prime Minister's Broadcast on the Suez Canal (1956). Portraying the overthrow of Nasser as essential for securing peace and preventing "a larger war" in the Middle East, Eden also stated candidly that the war was to be fought over what he considered to be British national interest: "Our survival as a nation depends on oil, and nearly three-quarters of our oil comes from their part of the world.”

The Suez Crisis was brought to an end in November 1956 by the Soviet Union's threat of intervention on Egypt's behalf. Nevertheless, Israel occupied Gaza until March 1957. Exposing their country's expansionist policies, future prime minister Golda Meir described the strip as "an integral part of Israel", while future prime minister Menahem Begin stressed that Gaza was Israel's "by right."68

Israeli soldiers relaxing during the invasion of Gaza from Israel Takes Gaza (1956). Image supplied by British Pathé.

While a total of five newsreels rationalizing European military intervention against Egypt and in support of Israel were screened in 1956, none of the films on the Israeli occupation of Gaza were screened. An unissued three-minute reel, Israel Takes Gaza, includes scenes of Israeli forces, and "tanks and trucks on the move and bombing taking place", and medium to close-up footage showing well-armed Israeli soldiers sitting on top of tanks. The reels humanize the invaders, showing them relaxing, smoking, and laughing. Sandwiched between those scenes are long shots of Gaza's Palestinian residents, walking with their hands raised in what appears to be a detention camp.

Had these images been screened, they would have contrasted with what British audiences had previously been presented of Israelis— peaceful settlers whose advanced European society was threatened by Arab backwardness, or desperate refugees from Nazi oppression requiring a safe home in Palestine. Pathé's projection of Israeli military prowess and the positive portrayal of Israeli soldiers reinforce an image of Israel’s superior national identity and morality in conflict, emphasizing affinities between the macho military culture of a former colonial power, which once saw itself as a guardian of law and order around the world, and an emerging settler colonial force that had taken over the mantle of control of the region.

Palestinians under heavy Israeli military guard from Israel Takes Gaza (1956). Image supplied by British Pathé.

Pathé’s coverage of the 1956–57 Israeli occupation of Gaza obscures the fact that the period was "characterized by widespread brutality"69 through its positive portrayal of Israeli soldiers, as is clearly seen in another reel, Israeli Food Distribution to Gaza Population, which shows Israeli soldiers providing rations to crowds of Palestinians. While the reel frames Israel as a moral state, the occupiers' provision of "aid" to a colonized population would have been a deeply humiliating experience for Gaza's residents. Nearly a decade after the Nakba, Pathé finally acknowledged the presence of Palestinian refugees in Gaza in a forty-nine-second report entitled U.N.R.W.A. Aids Gaza Refugees. In this newsreel, Pathé swings between representations of the Palestinians as passive victims and as threats. Against a wide shot of a crowded street, and the Israeli flag waving atop an administrative building, the narrator says, "Life returns slowly to normal in Gaza under the Israeli occupation." Over footage of Palestinians interrogated by Israeli soldiers, the voice-over claims that "the inhabitants accept the situation philosophically." The reel documents Israeli soldiers carrying out a house-to-house search, checking identities as the narration notes "much underground Egyptian activity", and Israel's need "to guard against hostile infiltration."

The phrase "hostile infiltration", in addition to describing small-scale armed resistance, was also used to refer to unarmed refugees who crossed the Israeli-imposed fence in a bid to return to their lands, effectively incriminating refugees exercising their internationally recognized Right of Return. "As many as 5000" civilian Palestinian returnees were killed "by IDF [Israeli Defense Forces], police, and civilians along Israel’s borders between 1949 and 1956."70 This went unreported by Pathé, which systematically reproduced Zionist rationales while concealing Palestinians' perspective, leading to contradictory claims: the Gazans "accept the situation philosophically" but are also guilty of "hostile infiltration." Filiu notes: "Despite the scale of their tragedy, the Palestinians who became refugees in the Gaza Strip in 1948–49 were far from passive in accepting their fate… it was the hope to return to a land that was sometimes very close indeed that drove this community of undiscouraged exiles. Neither minefields nor violent repression halted that continual flow of infiltration into Israel."71 In fact, Gaza constituted a nightmare to Israel during its first occupation.72 Michael Bar-Zohar, Ben Gurion's biographer, wrote of the leader's joy over the Israeli army's "spectacular victory" in Gaza and the Sinai. However, when Ben Gurion visited Gaza, "a new reality was revealed before his eyes, which shocked him deeply: the Palestinians did not flee from the IDF as they had in 1948."73

This history contrasts starkly with Pathé’s depoliticized spectacle, which portrayed refugees in accordance with the iconography of the "universal" refugee in postwar Western humanitarian discourse. The reel includes shots of refugee children queuing for "food supplies", provided by UNRWA, and the narrator emphasizes their plight, noting that "milk is a luxury to them, and who can blame them for a taste before getting home." Until 1967, most images of Palestinian refugees reflected "a naturalization of refugee history."74 Early humanitarian films presented a rupture between the reality of the refugees and their previous lives, as if the exodus was the starting point of their history. This is integral to the depoliticization and "humanitarianization" of the Palestinian refugee, a by-product of unrwa welfare programs that began in 1950.75 The treatment of Palestinian refugees as a humanitarian rather than a political issue also illustrates the exceptionalism of the Palestinian refugee case in the evolving international human rights regime.76 Again, this did not go unchallenged by Palestinian refugees themselves: the UN’s early accommodation with Israel provoked the resentment of Palestinian refugees, who in the 1950s and 1960s, called for the "burning of UNRWA ration cards", to challenge their classification as humanitarian victims that they saw as threatening to their political rights.77

In March 1957, under international pressure, Israel withdrew from Gaza. By then, the UN had stationed an emergency force on Egypt's Gaza frontier with Israel. A 1957 Pathé newsreel, Ben Gurion Stands Firm, praised Ben Gurion for Israel's withdrawal, overlooking his and other Israeli politicians' expansionist dreams. The reel also gives credence to the "right-wing" Israeli crowds protesting the end of the short-lived occupation, claiming that "they have little faith in the UN’s ability to halt a new outbreak of the hit-and-run fighting which has kept Israel's frontier in a permanent state of siege ever since Israel was founded." Once more, the voices of Gaza's Palestinian refugees were unheard, and the siege imposed on the Palestinians in Gaza is evoked as an issue for which Israel deserved sympathy.