The works of Sama Alshaibi reflect the realities of Palestinians by challenging hegemonic understandings of their world through idiosyncratic multi-media artworks. Her practice often refers to her own body as a site of performance which speaks to gendered positions and the effects of migration and war. Her work has consistently breached the topic of Palestine based on her own reality and position as a member of the Palestinian diaspora.

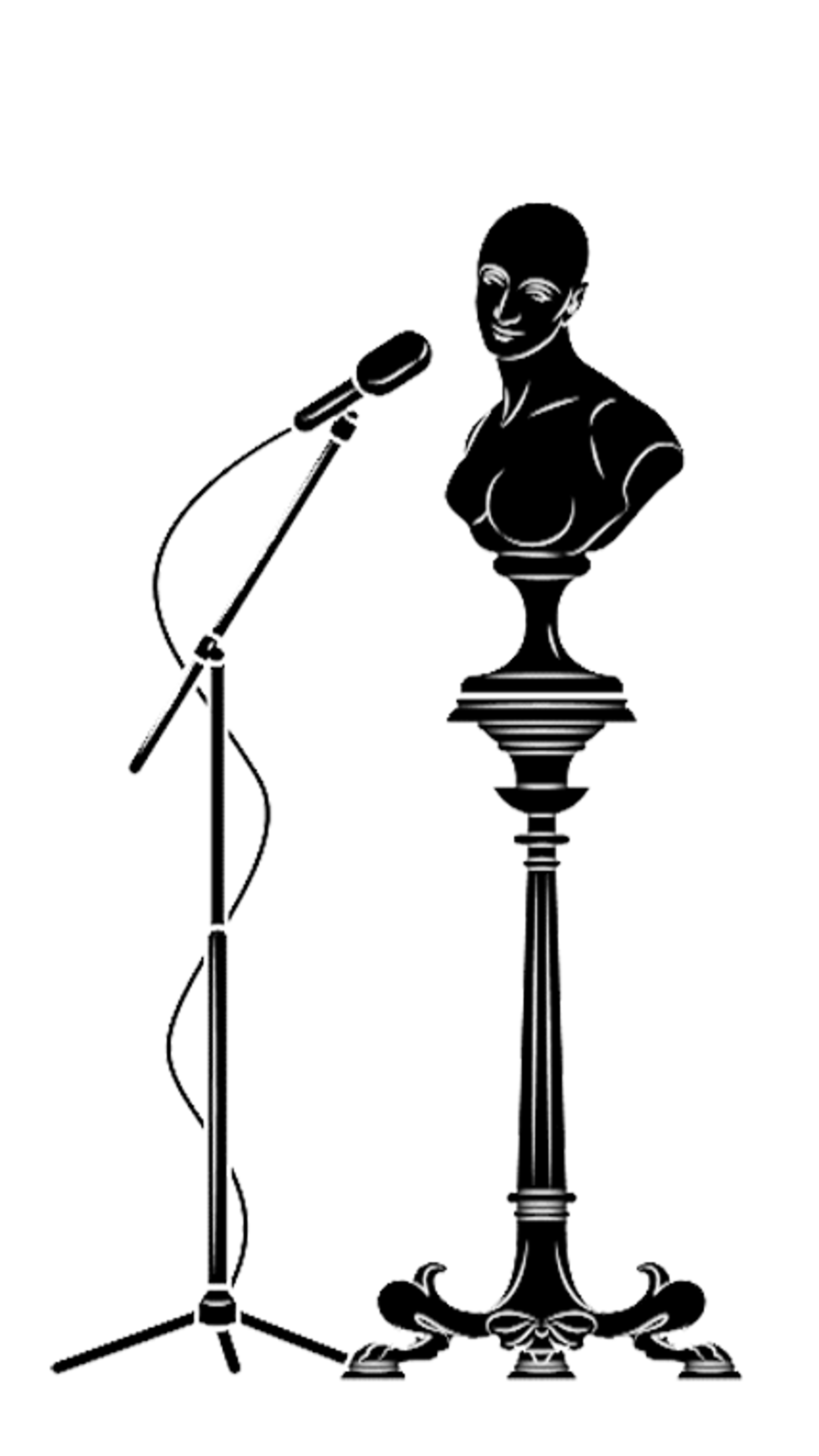

In The Tethered (2012), 48 moving image circles frame the Palestinian struggle through a reference to the date of the violent establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. This tessellated representation goes beyond images of plight and suffering that typically frame Palestine, such as border turnstiles, guns, burning buildings, and soldiers. Instead, the numerous screens are interrupted by quotidian forms of resistance. Palestinian flags wave while handcuffed fingers gesture with peace signs. Families kiss as they reunite after arrests—finding a place for hope within an unbearable history.

Using her own archive of video documentation accumulated over 12 years, Alshaibi manages to give a more nuanced view of life under Israeli occupation. The normalized, monotonous tune of mainstream media is replaced by a fervent belief and personal experience. Alshaibi privileges a more intimate picture of the struggle, where everyday life takes on importance and demands a reconsideration of the hegemonic depiction of the Palestinian cause.

Sama Alshaibi / Generation after Generation, 2019. Screenprint mixed media.

Generation after Generation (2019) is a series of screen prints that explores the visual language of Palestinian political posters from the 1960s and 1970s. The series focuses on the influence of revolutionaries such as Leila Khaled. As a female freedom fighter, Khaled’s actions such as the infamous hijacking of TWA flight 840 in 1969 challenged Western stereotypes of Arab women as docile and oppressed. Working with international colleagues in solidarity with the Palestinian cause, she became an iconic symbol of revolutionary resistance around the world. The series also draws parallels between the struggles of fighters and farmers, highlighting their collective quest for liberation and underscoring their deep-rooted connection to the land as a unifying theme.

The series is marked by the repetition of the Palestinian keffiyeh. It was originally worn by farmers as a form of protection from the sun. During the Arab revolt in 1936-1939, revolutionary commanders ordered all Arabs to don the keffiyeh as a form of identification with the land of Palestine. During the 1960s the keffiyeh returned in force with the rise of Palestinian resistance. Leila Khaled was one of the figures who contributed to its rise in popularity - along with internationally noted figures such as Yasser Arafat, she appeared in highly mediatized images with the keffiyeh over her head and face, she succeeded in degendering the garment which had previously been worn mainly by men.

Today, the keffiyeh is considered an international symbol of solidarity with the Palestinian cause and can be seen in protests around the world. Its pattern connects revolution to its origin with farmers and rootedness to the land; it is adorned with patterns based on the olive leaf—the most enduring symbol of Palestinian identity and resistance.

Catalogue (2019) critiques and subverts Western media representations of Palestinian life. Directly incorporating British Pathé newsreels made between 1935 and 1965, the work emphasizes the scale of Arab women's objectification within Western media. The scenes see Palestinian women kneading dough, carrying vases, picking oranges, and trying on clothes—their objectification is only magnified by the insertion of footage of Alshaibi herself as a human water feature.

Yet again, the artist dethrones the dominant narrative. The second half of the film presents footage of female fighters—the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s 1960s media strategy to counter that of the British—thus suggesting a lacuna in the Western narrative. In such a way, Alshaibi intervenes in a dominant narrative that insists on the Palestinian woman’s passivity, pointing the finger at colonial media tools, and equally using video to reify the Palestinian perspective.