In 1962, J.G. Ballard published The Drowned World, a novel set in a science-fiction scenario in which global warming has caused significant sea-level rise. The author adapts the Freudian concept of “regression” - or a psychological defence mechanism that causes the long-term reversion to the ego at an earlier stage of development - to physiological and genetic adaptations of species in the face of the climate crisis.

Beverly Buchanan, Marsh Ruins, 1981.

In the history of modern art, at one point the denomination of “Land Art” was created. At that time, they didn’t know how much of it would one day become inaccessible under the roaring waves.

The greatest trip I ever took was across the ocean to North America. I visited Beverly Buchanan’s Marsh Ruins (1981), a classic work of the Land Art movement which she placed in the Marshes of Glynn in Brunswick, Georgia. As the title of this work implies, she envisioned the piece as a ruin from the start, something that would wear away and whose gesture was always more important than its eventual object. The piece references folktales of the American South and unmarked sites of history. The marshland was the site of an 1803 mass-suicide of Igbo people who drowned themselves to escape enslavement. Buchanan’s earth mounds were a temporary monument that recorded the relationship of Black people to landscape and commemorated an invisibilized piece of American history.

Since then, this story has been an obsession in my mind, and how the underwater worlds of black American culture were not only history, but contained the seeds of a dark future. The Glynn marshes were an area that were heavily endangered by sea-level rise and one of the first areas to disappear below the water, like so many ancestors. The underwater stilted houses are today regarded as one of the most beautiful ruins of the old world. And these poetically reside next to Buchanan’s gesture of absolute temporality.

James Turrell / Celestial Vault after renovations in 2008. Photograph by Gerrit Schreurs.

Rather than a metallic monument piercing towards the sky, she decided to make the mounds out of concrete and tabby was already a surrender to the sea - a force much greater than the violence of humanity. A gesture that was knowing of the fact that place will remain and that her act would give validation to the site for generations whether above or below the water, whether it was visible or invisible, and that maybe just the intention of trying to find it was parallel to that wild grasping of history in a country that tried as much as it could to obscure and obliterate any memory of the living conditions of humans in the time of dry land.

I find myself back at home, swimming above what used to be the shores of Holland. Since the moment that the waters breached the dykes and sank the land into irretrievable oblivion far before scientists had predicted, humanity has evolved into more amphibian forms. My barrel-shaped chest serves for greater oxygen intake as well as a floatation device so that I can nap on the surface of water. This combined with the flaps of my nostrils allow me free dive into the post-flood remains of the once-bustling metropolises that we now refer to as the Benederlands (the Belowlands).

As a child I read the ancient texts of the Mahabharata that perfectly described what happened to the coastal cities of the 21st century all the way back in 1500 BC. Although warnings had been given in the 20th century, and alarm bells had been rung in the early 21st, the rulers of these sunken cities failed to implement any course of action to prepare for the catastrophe.

The sea, which had been beating against the shores, suddenly broke the boundary that was imposed on it by nature. The sea rushed into the city. It coursed through the streets of the beautiful city. The sea covered up everything in the city. I saw the beautiful buildings becoming submerged one by one. In a matter of a few moments it was all over. The sea had now become as placid as a lake. There was no trace of the city. Dvaraka was just a name; just a memory.

— Mausala Parva of Mahabharata

James Turrell / Celestial Vault, 1996

Like my parents, I am a diver - I search for objects in the flooded lands that I can dry and fix for sale up the expanded breached rivers. Even though demand is waning, I can still make a living with scrap materials, metals, and rare historic finds. When the catastrophe unfolded our ancestors split in two - those who feared the water and moved to higher land, and those of us who remained, attempting in any way possible to survive off of sunken territories on floating houses and buoyant platforms. The ones who fled to land still try to live in old ways even if they fail to do so and even if it becomes increasingly difficult with time.

Objects are easy to bring up to the land-dwellers, but there are other things that they will never see that I like to keep to myself. My favourite such place is James Turrell’s Celestial Vault (1996). It has been underneath the sea for years, but I know the way to the crater on the seafloor like the back of my hand. I found it accidentally by observing a strange indentation in the ground, while searching for objects near the old site of the dunes I brushed off a clump of crustaceans and debris to reveal a plaque with still-legible information about the work. Since then I have made it my task to maintain the central bench by clearing off growths and algae. The work was originally built for a festival of Landscape Architecture which now is a seascape. Every time I visit this part of the sea I take the time to freedive into the central structure and stay as long as I can in a single breath.

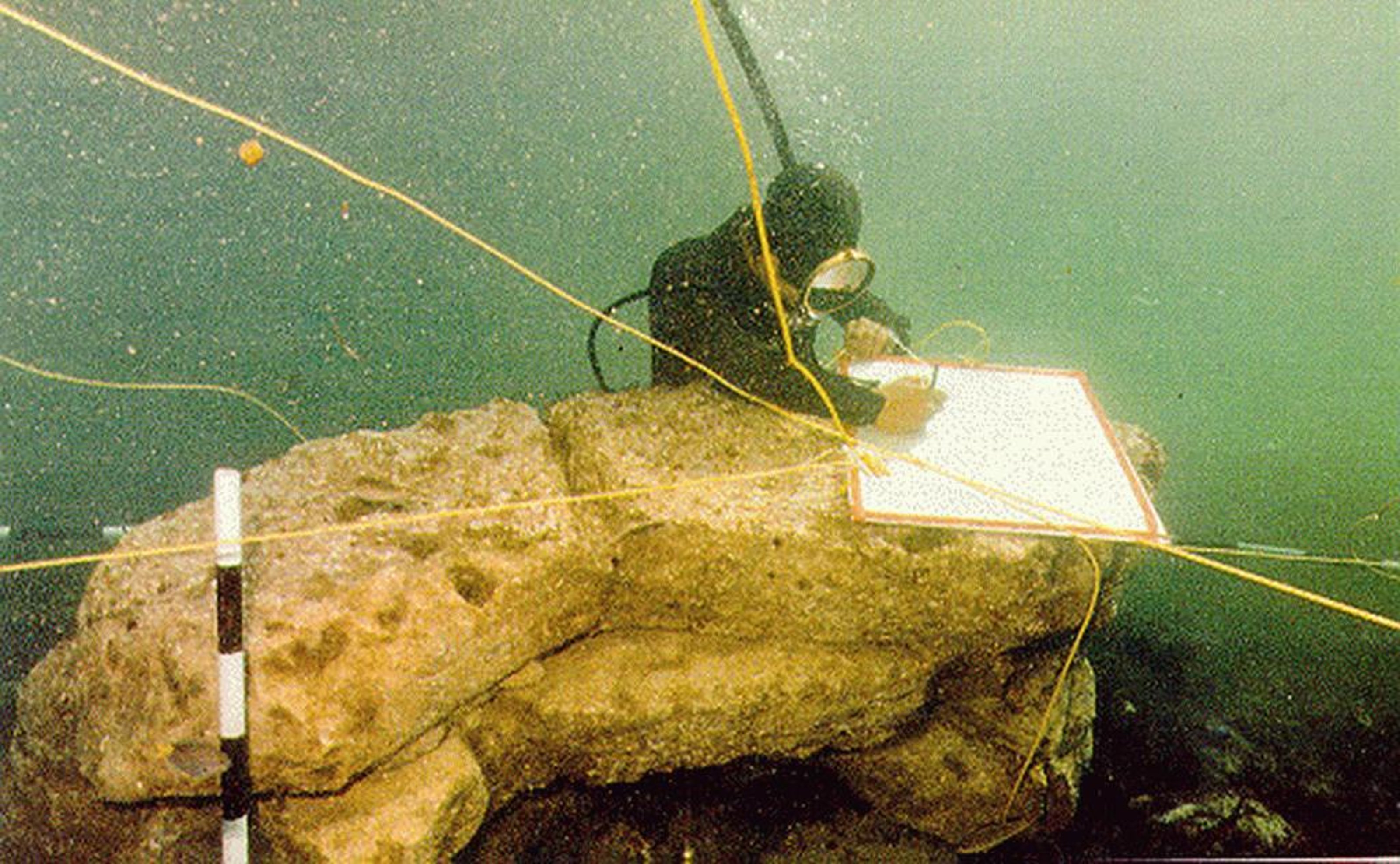

An underwater archeologist in the ancient city of Dwarka 36 meters beneath sea level.

In the past, visitors used to climb a dune and then walk a 6-metre concrete path to a stone bench located in the centre of the crater. From here, you can lie down and observe the sky in beautiful isolation, transforming a mundane view into a magical realisation. Today, I swim to the surface of the water above the centre of the crater with my goggles and look down on its immensity below me. I position myself on the surface of the water directly over the bench, breathe in as deeply as I can, and submerge myself. The trick is to point your head directly at the sea floor and use the impulse to dive as deep as you can, like a peregrine falcon does in the sky. As I start to slow, I continue to swim down until I reach the bench and grab hold of it. Then I can use my arms to anchor my body onto its flat surface, and stay put, levitating above the stone.

It is a different experience than when people looked at the sky from a dry crater. I look up towards the sky and I see it twice - the first is the dancing surface of the water that gives way to the clear blue of an infinite sky. A grey fish swims above me, and I let out some air bubbles from my mouth and watch them travel to the surface and break the barrier of the sea into that wide open circular sky. When I feel the kick in my lungs that indicate that I’m running out of air I let go of the bench and push off of it with my feet, and I let the buoyancy of my body do the rest. Closing my eyes, I break the surface of the water and gasp for air.