Collecteurs x Jonathan Monk Capsule Edition: 10 unique receipt drawings

Jonathan Monk is a familiar affair in the contemporary art world. During the past decades the British, Berlin-based artist has well marked his ground with a practice that navigates an array of different elements—including that of photography, film, painting, and sculpture. Meanwhile exploring notions of context, the act of appropriation almost consistently finds its way into the process of new work. A personal narrative that in ways has become a trademark of his career. Paying homage to Ed Ruscha, Sol LeWitt, Jeff Koons, and other conceptual predecessors pertaining to his relevant immediacy, Monk introduces a myriad of dialogues that concern both past and future. His ongoing compilation of restaurant bills, that initially began during a temporary life with his family in Rome, is an example of his spontaneous appropriationist gestures. Readymades of Jenny Holzer or Donald Judd resurface in form of drawings on receipts which later on are sold at the very same price of the meal. Just like that, Monk’s collectors end up buying him dinner, an organic outcome that equally romanticizes and mocks the intricately connected relationship between artist and his enabler.

While the overall materiality of the ongoing series creates numerous constructive discourses—like the restless duality between authorship and originality—it’s the geographical investigation of artistic identity that lingers on most solemnly. The genesis of art: Where does it reside, necessarily at its beginning or can it also pour forth from its end? Does art—like most things in this world—inure to a conventional life cycle of birth and death, or can it last a kind-of-forever within the in-betweens? Monk’s appropriations hint towards a continuous voyage, in ways promising art’s ever-changing nature. New dimensions of meaning are evoked, over and over; the past, however, always survives within its recently-different history. His underlying subjectivities of existentialist concerns might seem onerous to some, yet the presence of their innate sarcasm establishes a personal lightness within the audience’s ingestion, converting the overall experience of the artist’s work into a somewhat perfect portrayal of human venture: How there’s a culmination of predictable gravity all around us, its bittersweet complexities present at all times.

Lara Konrad: Appropriation has been an ongoing topic within your practice, dating back to your days in art school. Some years ago you said during your studies you had realized being original was almost impossible, which served as an inspiration to use whatever was available. Do you still identify with that comment?

Jonathan Monk: It still makes sense, but perhaps I’ve realized that originality is subjective and easily manipulated to meet my own specific requirements. It depends on the weather.

LK: Ultimately speaking, all derives from subjectivity. When taking a look at Duchamp, everything he chose to appropriate served as a vessel for his very own sensibility. I’m not sure if appropriation is highly personal or impersonal. Balance is key, I suppose.

JM: The balance is where the borders blur slightly. The highly personal isn’t so personal anymore, or perhaps we all, however abstract, share certain things, certain things we can all relate to.

LK: A while back you began collecting restaurant bills, later on—in form of drawings—reproducing a work of another artist on them. The final piece is sold for the amount of the meal. There’s always been a beautiful gesture about appropriation, creating a silent dialogue between artists, between separate entities. What is it between eating at restaurants and appropriating someone else’s work that initially started this interest, and what other interest has it grown into/additionally after all this while?

JM: The project started when I lived in Rome. I moved there with my family for 18 months. From the end of 2014 to the middle of 2016 I lived in Trastevere. It was hard leaving my studio in Berlin, as in Italy, the living room table served as my work space. The restaurant drawings slowly took shape, very slowly. I tried to come up with a series of drawings, defined by working situation. The receipts given in Italy often tend to be quite elaborate and traditionally they are handwritten. The logic of adding something felt appealing.

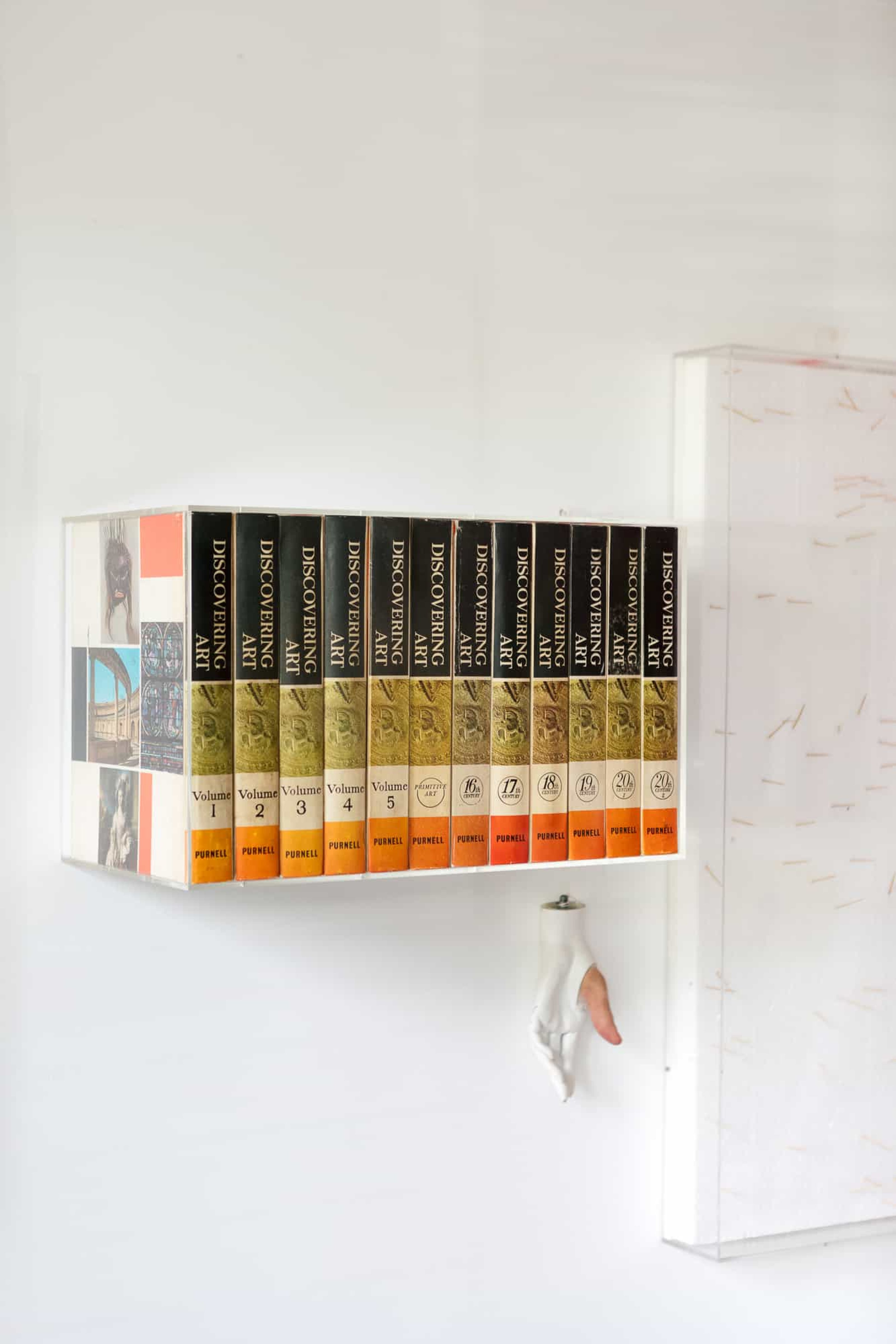

I tried to contextualize the idea. One of the very first was Bruce Nauman’s sculpture ‘From Hand to Mouth’ (1967). Even though the collection has grown pretty diverse at this point, I don’t think too much about each individual drawing or how they might fit into the overall project. The receipts changed once having moved back to Germany. Thermal paper isn’t ideal for pencil, although I’m slowly getting used to it. The sad truth is that the printed information will fade away eventually, but hopefully the drawing or painting will remain.

LK: There’s a romantic premise, though, within the process of information leisurely fading away. It adds a physical experience of temporality, repositioning the appropriated material once again. Once you were back in Germany, did the content of the drawings shift too? Considering the different atmospheric circumstances…

JM: They did change. This was due to the nature of the receipt—Germany is perhaps slightly more up-to-date and all financial paperwork is digitally printed on thermal paper with all the correct information in the right place. Thermal paper isn’t so easy to draw on. I started by simply making line drawings. It was easier to control things with shading, etc. I assume parts of the printed info will slowly vanish as is the nature of this printing technique and maybe my drawing will be the only thing left. We see, or not.

LK: Picasso’s ceaselessly referenced sentence, “Good artist copy, great artists steal.” What are your thoughts here?

JM: This sounds like my basic teaching syllabus, although I guess I try to manipulate the truth—

LK: What ‘recent past’ are you referring to? Suggesting only the recent past is full of treasures, because there hasn’t been enough time yet for its full exploitation?

JM: I like the idea of engaging with things from my lifetime. Perhaps it makes it easier to relate as they feel closer. For instance Richard Prince only collecting books from 1949 onwards. I know that diamonds take millions of years to form.

LK: Is a certain level of closeness necessary for appropriating work? In some ways it seems easier, yet also proposes a certain level of difficulty as there’s a specific connection and there within limitations. Now I’m also wondering about the characteristics necessarily existent within a work you decide to appropriate. Are there such things you seek before you begin, or does it continuously shift, organically?

JM: It continuously shifts, although of course some works lend themselves to manipulation. Sometimes the obvious is too obvious and sometimes too obscure. Again, it’s back to balance.

LK: How important is the conditionality of memory within the syntax of your work, as well as personally? I’m disregarding here the assumption that art is always personal.

JM: It’s very important. Both in an art historical context and within my own humble background.

We all bring something different to the table, so I can only relate directly to my own situation, but with the understanding that we all share certain similarities, however disparate.

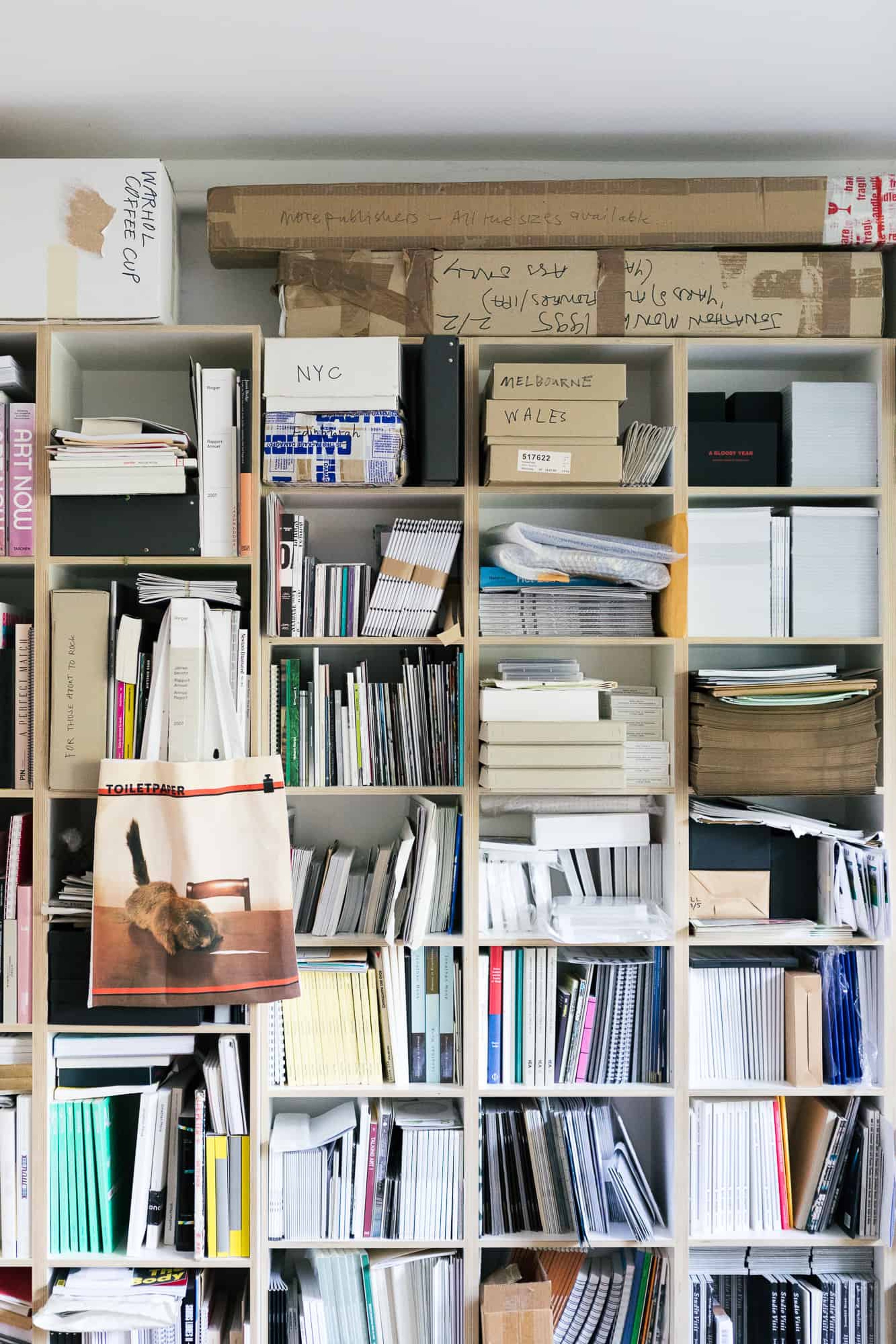

LK: Your studio struck me as very ‘archival,’ there are boxes on shelves, all types of books and documents everywhere. Do you collect a lot of things?

JM: Most people seem to think my studio is a bit of a mess, but it has improved. There is an archive of sorts, but perhaps it’s only me who knows where things are. I have a collection of artist books and some editions or multiples, and quite a lot of ephemera. I try to focus, though, I don’t just keep everything that comes through my letter box.

I spent a long time piecing Robert Barry’s Closed Gallery and Invitation Piece together. But now they are both complete. I have a lot of Sol LeWitt and Richard Prince books and 38 copies of Ed Ruscha’s Crackers. I also trade with artists as often as I can.

LK: During research, I often came across you talking about originality and this idea of being unique. It struck me, because I feel the strive to be unique has become somewhat outdated, extinct, yet it seems more present than ever. To be honest, for the longest while I’ve been confused about this idea of originality and rightful authorship. Hasn’t art always too been about exchanging ideas and influences, an infinite journey of homages and nuanced reflections? When can an artist call something his own? Would you consider these questions even relevant to your work?

JM: Things have changed drastically in the last twenty years. I was at art school before computers and mobile devices, the library was an active part of my studio. Whilst looking for Picasso, one would stumble over Picabia. Or Russian avant garde might lead to Ruppersberg. The internet has completely altered how things are seen and how they might be distributed. Everything is available to everyone in just a matter of seconds.

Sadly not everyone feels the same.

LK: What is at stake if originality is indeed matter of the past? I’m not sure if I agree with your statement. I think originality—at least in some form—does still exist within the context of art. It merely might have changed its circumstances, evolving alongside everything else, such as the ever-growing existence of the internet.

JM: The meaning of originality has shifted slightly and I think people continue to strive for a form of originality. I’m always interested in seeing how two works that share visual characteristics can have completely different meanings, and I guess vice versa. It probably has something to do with what cards you bring to the table.

LK: I think people will probably strive their whole existence for originality. It’s another way of reaching immortality, even if just temporary. I suppose one can say it’s in our blood. How has the idea of originality shifted?

JM: Maybe it has only shifted for me. I think originality is perhaps too specific. There are of course millions of original things done everyday, each one only slightly different to the same thing done yesterday. The process of moving forward is slow.

LK: What’s important, though? Is the very formation of ‘importance’ the beginning of art? It seems strange to actively pursue originality. But I guess, it’s just as valid as the pursuit of truth.

JM: It really isn’t important, the search for the unique. I think it’s perhaps interesting to find a way to navigate the apparently fixed parameters of art. This is all very basic though, and probably something we all went through at school or art school. What can and what can not be art?

LK: For whatever reason I’ve thought a lot about the beginning and end these past days. Something that can’t be answered correctly, of course, and is—in itself—never-ending. What’s your take?

JM: I think we, as artists, writers, etc., probably like the idea of being able to somehow control the edges of what may or may not be art. But this just makes it easier for us think about it. In reality I think art or ideas that could relate to art are everywhere, locating them is sometimes difficult.