The Tokyo-based Norwegian artist, Gardar Eide Einarsson examines structures of social conflicts in modern societies based on the interplay between authority and rebellion with a focus on expressions of power, control and suppression. The co-curator of the upcoming Prospect.5, Diana Nawi, interviews Einarsson for Collecteurs Magazine.

Diana Nawi: What have you done for your edition project for Collecteurs?

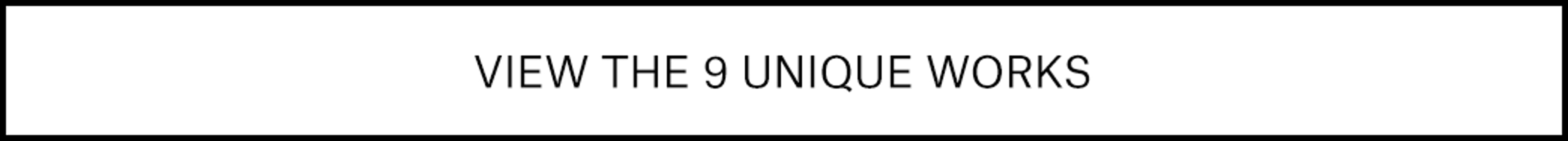

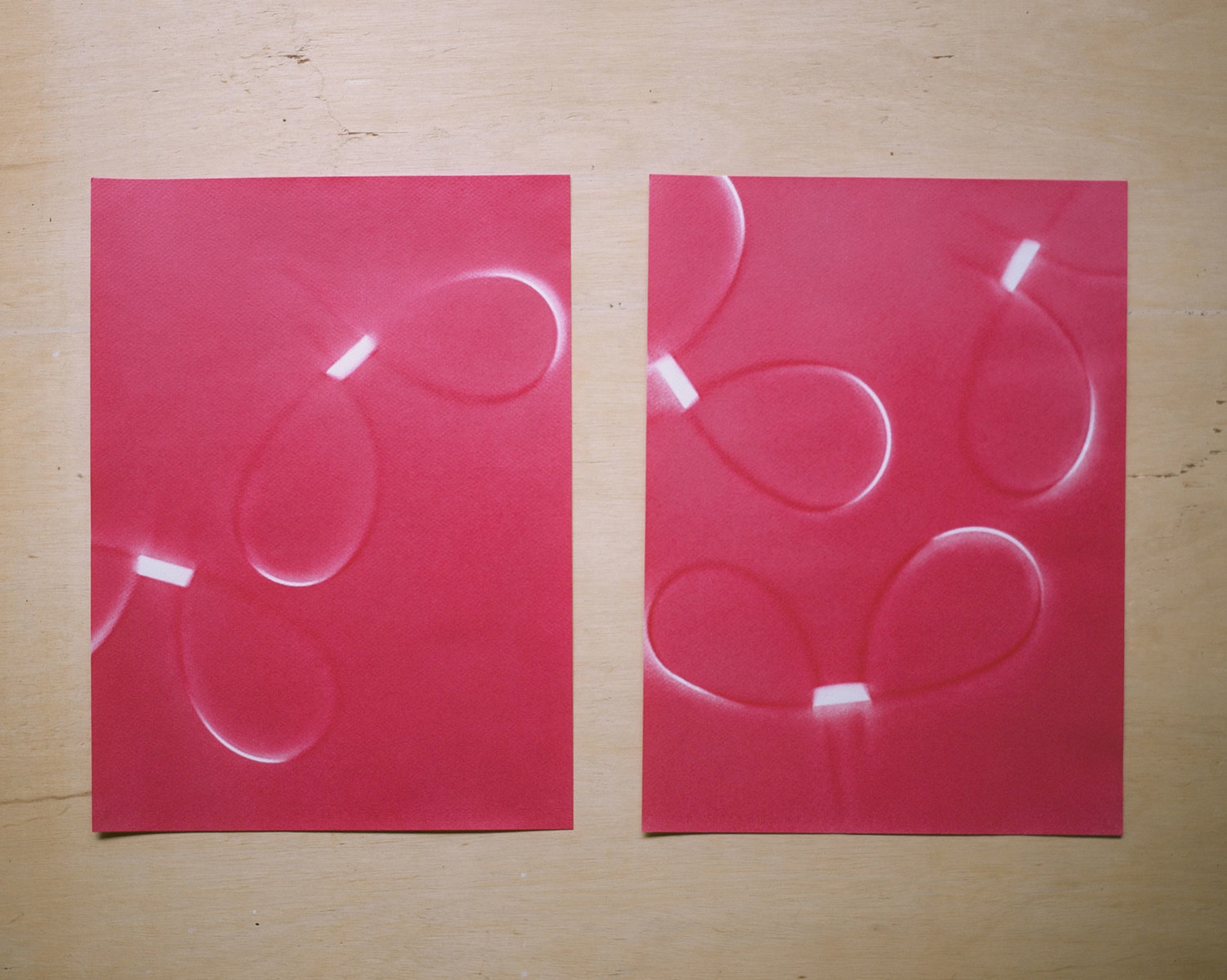

Gardar Eide Einarsson: My edition is a work on paper titled Zip Tie Disposable Plastic Double Riot Cuff (Red) and is made by laying out plastic riot cuffs on paper and spraying over them. The result is a semi-abstract pattern that takes on a very different meaning once you become aware of the object that created this pattern. As with much of my other work, I am interested in the history of the initial found object and in a delayed realization of the contents of the work, and I feel the abstraction is reminiscent of the way the actual violence that our institutions rely on is obscured in our society.

DN: Can you expand on that notion of “obscuring” on a social and institutional level? I’m curious about the idea of abstraction and the delayed realization of this phenomena as you refer to it, a sense of the insidious veiling of systemic violence. And, are you often interested in your formal processes having analogous/metaphorical relationships to these systems?

GEE: The idea of my processes and formal choices mimicking these systems is definitely something that interests me. In this way I feel like the work implicates itself in a different way, becoming more problematic and less of a disembodied critique. I am interested in the idea of obscuring, abstracting and withholding from two opposing viewpoints: One is how this is used from positions of power. In my work I feel like this is often an important aspect of how I use language, with a focus on a kind of emptiness that exists in contemporary American-English as it is employed by the ideological state apparatuses—something that has of course been turned up to 11 after Trump—and in my paintings, which at first sight take the form of content-less abstraction but are actually taken from quite sinister source materials which can usually be traced through the titles. The other approach to not revealing everything is how it is used from a position of oppositionality, as encryption, protecting one’s ideas from those in power and refusing to follow a certain marketplace logic of advertising and displaying the entirety of a work’s contents for immediate consumption.

DN: How do you think about editions or multiples as they relate to your larger project?

GEE: I like multiples and editioned work as they can be more accessible in terms of allowing more people to have a chance to own work. My work also takes different forms from piece to piece based on the material I am working with and for some things I feel like smaller and/or editioned work is somehow more appropriate. Editions are also a good way that artists can support valuable initiatives in the art world and beyond.

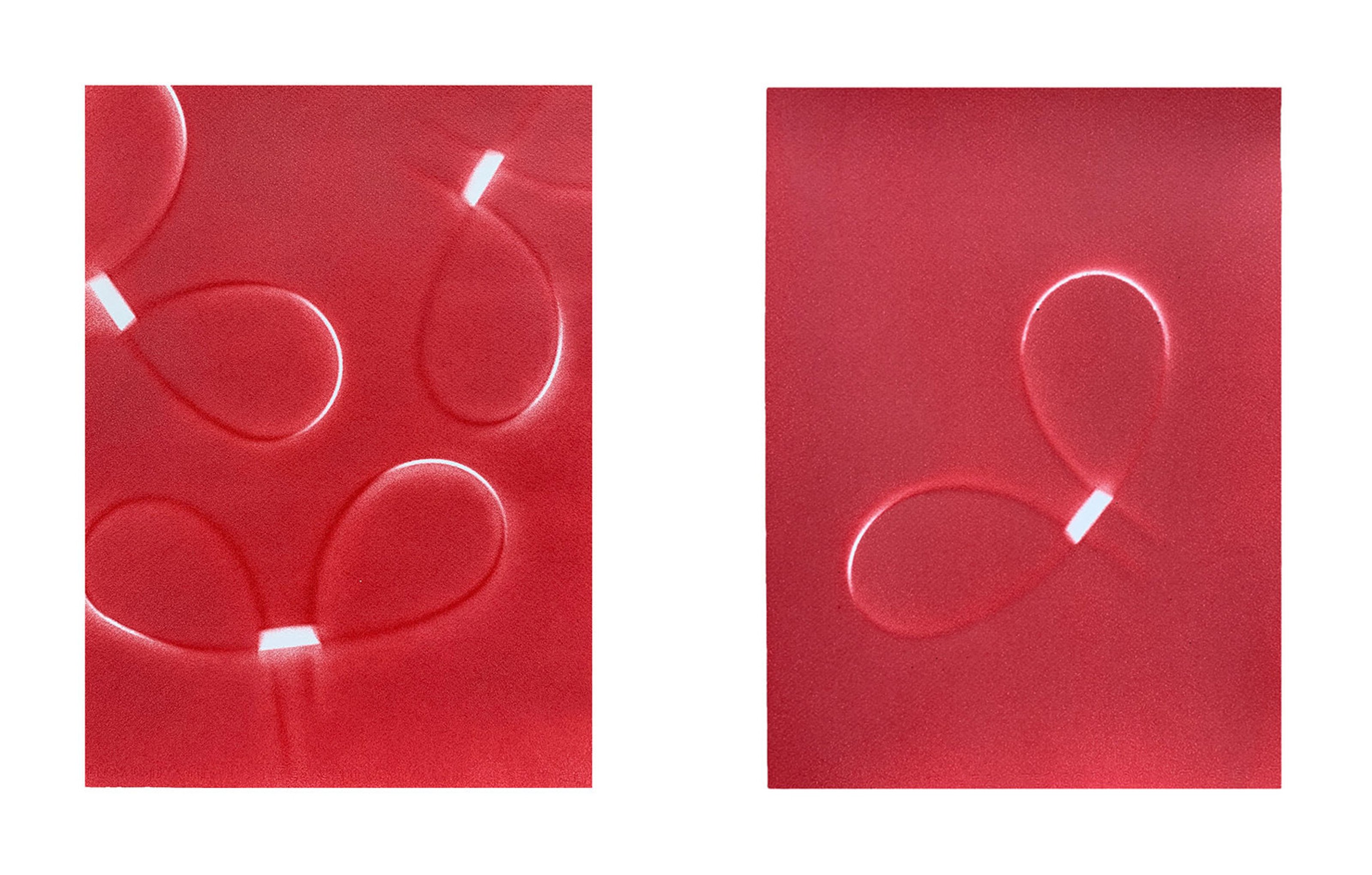

Gardar at his studio in Tokyo © Gui Martinez for Collecteurs Magazine

DN: Can you talk about the initiative that your edition will go to support?

GEE: The entirety of my share and some of Collecteurs’ share will go to a charity I became aware of through moral philosopher Peter Singer’s organization Network for Good which rates the most effective charities in terms of lives saved per dollar contributed. The charity is called Development Media International and uses TV, radio, and mobile campaigns to change behaviors and spread science-based knowledge in developing countries particularly with regards to child health and reduction of infant mortality.

DN: I was recently working with a private collection in Miami and came across this great work of yours, which was the stencil for a chain link fence that one could repeat over a wall. It was such an interesting way to think about selling and distributing work but also about display, because presumably it can become a background for other works. Is that an edition? What was the thinking behind creating a kind of DIY work for people to collect, interpret, and live with?

GEE: That work was an edition of three. I was interested in, as you say, making an art piece that could work with the work of other artists; as I have displayed it in the past it has been with other work, by myself or by others, hanging on top of it. Whenever art is displayed it has a relationship to its surroundings and often with the work of other artists and I wanted to make a work that embraced this rather than resisting it. I also wanted to make a work that would fill your field of vision and somehow just create an ominous environment, a kind of unpleasant wallpaper.

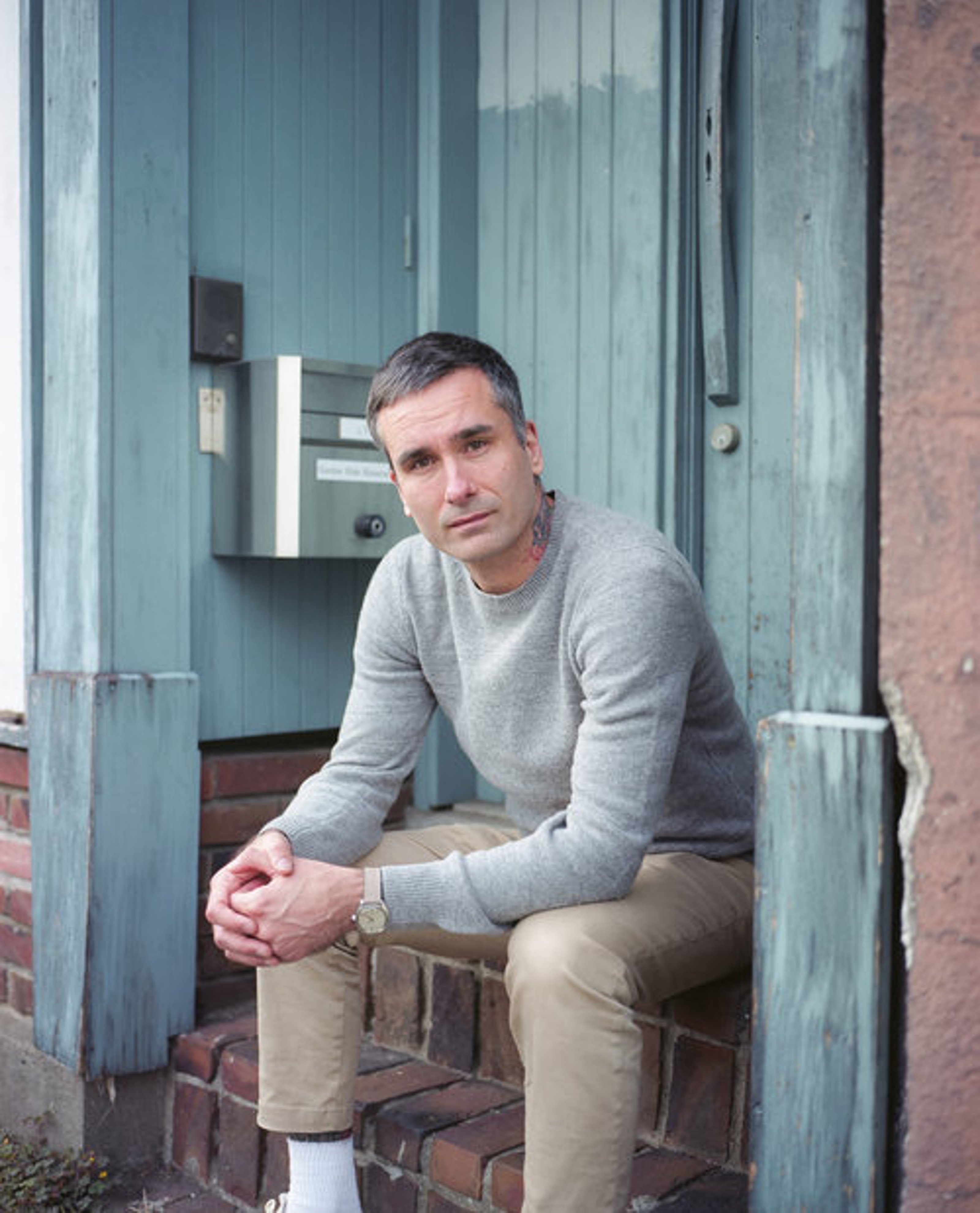

A selection of research material at the studio © Gui Martinez for Collecteurs Magazine

DN: Can you expand a bit on the way in which you determine the “different forms” for your work? Perhaps the question is, where do you start when you’re making a work (research, idea, material, outgrowth of another project, etc.) and how does that develop? I assume it’s a varied process; your work strikes me as very ideas-based but there’s also such a particular approach to materials, so I wonder about the relationship between these impulses.

GEE: I usually start out with a source text or images that I want to use. Then the actual material form of the artwork comes out of what I think would be the most interesting way to talk about that source. Sometimes I will find source material that I am not sure how to translate into an effective artwork and it ends up just lying around sometimes for years until I can come up with a way of using it in a way I am happy with–and of course some material ends up never being used. It does happen sometimes as well that the work is a direct development of an earlier work, or series of works, where I will feel that there is something potentially there that I was unable to get all the way to in earlier attempts. There is also always a certain self awareness of the work’s existence as art and within an art institution and the potential problems and contradictions this entails so that will also affect what form I choose for certain projects.

The artist’s studio © Gui Martinez for Collecteurs Magazine

The family home in Tokyo was designed by architect Kazunari Sakamoto © Gui Martinez for Collecteurs Magazine

DN: How has living in Japan affected your practice? So much of your work relates to the interaction between state and individual, and I think of that as such a critical question in trying to understand some of the cultural context of Japan. Has that entered into your thinking as you’ve been there, or are there other ways being there has influenced your thinking or making?

GEE: Moving from Norway to the US as I did in 2001—on the 10th of September of all days—I felt like there was a big difference in the relationship between the individual and the larger community and in how the state figured into this relationship. There was definitely more focus on the notion of individual “freedom” and that when the state was forced to intervene it did so in a more blatant way. State monopoly of violence seemed more explicit in the US, something which at first glance paradoxically, but not really, went hand in hand with a stronger sense of individuality.

Then moving from New York to Tokyo the pendulum swung even further back, Japan being a place where there is an even greater focus on community and social cohesion than in Norway and where individual behavior is even more self regulating, governed by what Kojin Karatani talks about as “the laws of the community” where rules are rarely explicitly stipulated and rarely need be enforced because they are so successfully internalized. But, of course, Japan is also very complex and dense and so individuality, dissent, and difference comes to be expressed in different ways.

DN: I studied abroad in Sweden and have been to Japan twice and was definitely struck by the similar nature of the social cohesion; such a strong sense of community and social responsibility but also the other side of that felt like this vague sense of repression or loss of individuality. Coming from the US in particular–which is so married to an idea of self-expression above all else–it was striking.

GEE: Yes, but then there is at the same time in Japanese culture a real tradition for expressing individuality which is evident in their aesthetic tradition and nowadays if you look at contemporary Japanese residential architecture for example you have much wider variance and tolerance of difference and originality than in Europe or the US.

Einarsson at home © Gui Martinez for Collecteurs Magazine

DN: There is a lot of discussion of “now more than ever” in the US art world in relation to the current political and social landscape, a sense of trauma and fear, as well as a—perhaps unmet—desire to “resist” in some way. There is also a vague sense of kind of end times looming; I wonder if and how you feel this where you are?

GEE: Well, in a way these kinds of feelings of a desire to resist is something I have always thought of and which my work has always been about. As I mentioned, I moved to New York the day before 9/11 and so my introduction to the city as my home was to a city and a country in a state of exception. Then, too, there was a lot of nationalism and a very real sense of the presence of violence, not least the violence wielded by the state, but also violence towards groups considered not part of the “people.” Of course Trump is such a cartoonish manifestation of all of the dark aspects of the American narrative but as I see it this was present long before he was the one in the White House. That said I do think that it is important that the art world, and everyone else, stands up to the sheer obscenity of this president and how he and his administration are trying to wear down the institutions of civil society. And of course, it is also not only Trump, there is also a more or less worldwide move towards autocracy and away form the liberal democracy that had up until recently seemed like such a teleological inevitability.

DN: Your show at Team Gallery’s space in Los Angeles in 2016 was simultaneous to the election and it is possible, in hindsight, to read it and much of your work as prescient in many ways–predicting aspects of this moment that are allowing what was formerly repressed or swept to the side to rise to the surface of our collective consciousness. Do you feel a shift in context, or in reception these days? Or, is the proper question: do you feel like this moment was an inevitable outing of what has always been there?

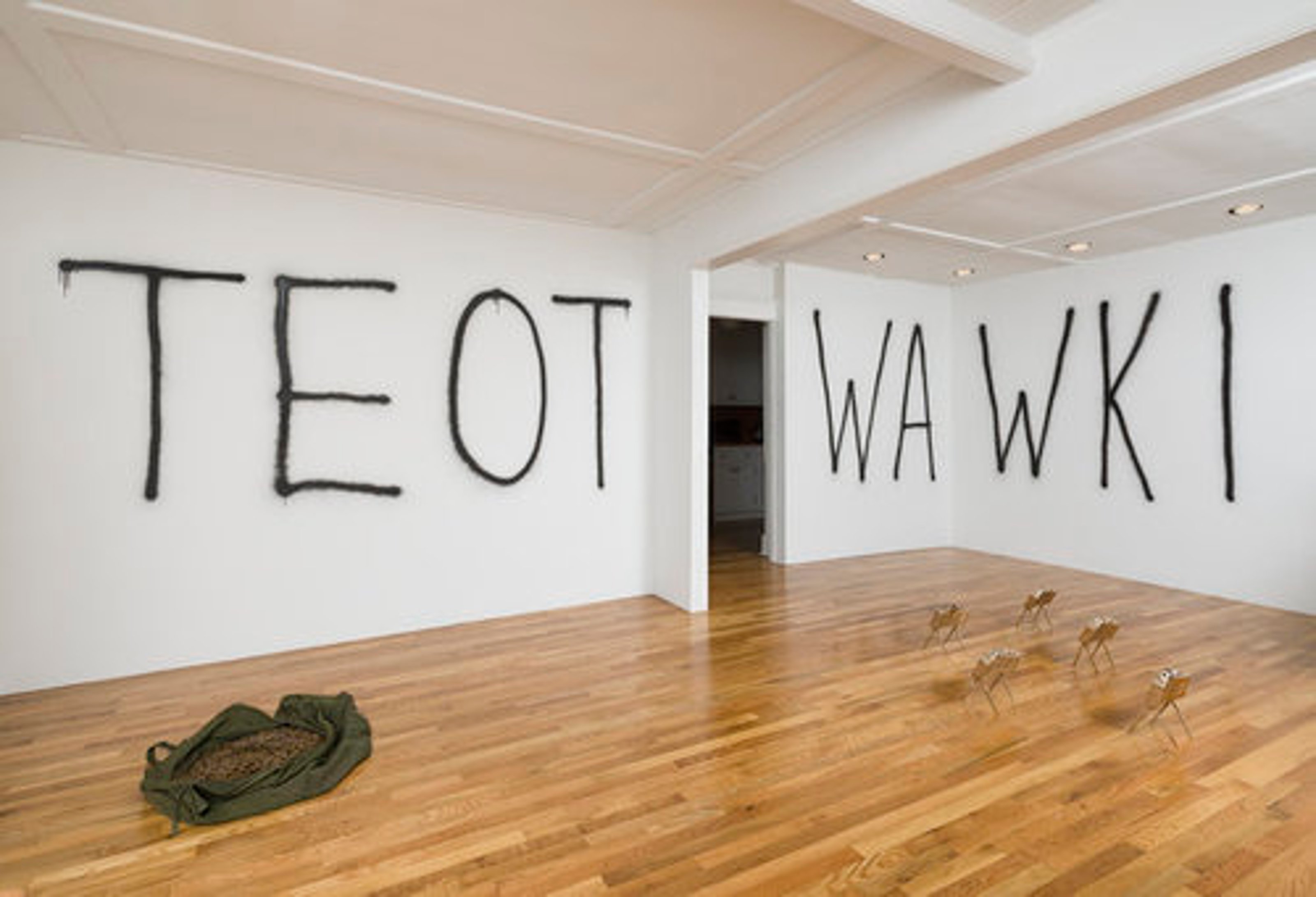

Gardar Eide Einarsson, SHTF (Team (bungalow), Los Angeles, 2016)

GEE: My show at Team (Bungalow) in LA opened a week before the elections and there was a real sense of foreboding then with regards to Trump. One of my pieces in the show was a wall painting with the acronym “TEOTWAWKI,” which is shorthand in survivalist fringe groups for “The End Of The World As We Know It,” and in many ways that is exactly how it feels now looking back to the election of Trump. I don’t feel like this moment was inevitable, and to be honest I kind of couldn’t bring myself to believe he would actually win, but I do feel that the bigotry, callousness, and violence he has channeled–and probably intensified–was always already there. My work has always been very much focused on the idea that there is violence lurking under the surface of and underpinning our society, but that violence has become much more explicit recently. Of course there were always people for whom the violence was never not explicit, those who were excluded from the state or who were incarcerated or punished by the state–or those whom the state allowed to be excluded or punished by others.

Works in progress at Einarsson’s studio © Gui Martinez for Collecteurs Magazine

DN: Can you talk about the tone of your work, how you see it functioning, or how you would like it to function? I have a visceral reaction to it; something like a feeling of being unsettled or entering into the psychology of these subcultures or anxieties. I don’t get a sense of catharsis, but rather can feel enmeshed into the space of this fear or violence. But I wonder how you see it operating in the gallery space, and perhaps more broadly in the public sphere? What do you ask of it when you’re making it and exhibiting it?

GEE: Well this is some of the reason why I want my work to abstract itself and be a bit emotionally distant from the source material. I don’t aim to recreate a certain type of feeling of the real world made to perform itself within the white cube but rather to present something within that “dead” space–using the accepted language of the institution to present certain material for consideration. I also always aim to leave a lot unexplained in terms of source and intention so that it is clear that the work is not some pre-packaged and finished narrative but rather suggests points to think around. One of the aspects of the art world that I appreciate is that I think there is a potential for a longer exposure intellectually. Contemporary art usually does not affect the viewer in quite as direct and emotional a way as some other forms of culture, but to me it allows for recontextualizing and presenting material that leaves the viewer with quite a lot of agency in terms of how to go on thinking about or processing that material.

© Gui Martinez for Collecteurs Magazine

Gardar Eide Einarsson Zip Tie Disposable Plastic Double Riot Cuff (Red), 2018 Collecteurs Capsule Editions

DN: I just saw a new exhibition of Will Boone’s in LA, and I think he’s part of a generation just below you that likewise is asking certain questions about the space of these paranoid and real fantasies of violence, control, and anti-authoritarianism (and relying on similar formal considerations). Whether it’s the work, or the moment we’re in, I couldn’t help but thinking of it through a lens of identity politics–in this case, a sort of angry white male positioning and the particular fears of this group within the US of their possible obsolescence. Is this identity positioning something you think about in your work?

GEE: I see my own position as a little bit different. I came to the US as a student right before 9/11, when nationalism was running quite high, and then after twelve years or so I moved to Japan where I live now. I have lived outside my home country for the last 20 years, so I have always felt aware of my status as non-citizen and my interactions with the state–and therefore my sense of security and protection within it–was always very informed by that knowledge. My usage of a certain type of American aesthetic and myth-making came out of an outsider’s observation of it and to me does not represent comfort or nostalgia but rather strangeness, and to some extent threat.

DN: Your show last year in Japan was exclusively paintings. Is that reflective of your studio practice–are or were you only making paintings?

GEE: Being here in Tokyo is a bit like being in exile from the art world, which I am enjoying quite a lot. This as well as having a young family has led to very regular studio hours here which lends itself well to painting. I was also interested in focusing on painting as a very direct, DIY way to produce meaning, with as much in common with fanzines as with a certain masterpiece tradition of painting. This helped me disregard a bit the anxiety of influence that can be so stifling with painting. I was still making other kinds of work but felt like I was able to productively concentrate more on–and enjoy–making paintings.

Gardar Eide Einarsson Studies and Further Studies in a Dying Culture (Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, 2017)

DN: Can you talk about your recent shows with Team in NY and Standard in Oslo?

GEE: Both of these shows addressed the current moment. The show at Team, titled Flagwaste, was just one sculptural installation made up of the leftovers and refuse from US flag factories, a meditation on what is excluded and refused in order to create the “us” of the nation. The show at Standard, titled Rawhide Down, after the Secret Service code that signaled that Ronald Reagan had been shot, was an all painting show consisting of a series of large scale portraits of state leaders who have been the subject of assassinations or assassination attempts