Collecting art is a complicated practice. In his course, Collecting as Practice – What Makes a Work of Art Work, writer and curator Andrew Renton claims that the process of collecting works of art is a practice, a kind of continuity of activity. “It is not the singular acquisition of objects, but it is the continuity of the process of things coming in and being redistributed in all their ambiguity and with all the problematics that come with that.”

Already a practice that required constant attention and judgment, collecting as a practice is also baffling in terms of its impact on the status and the very nature of a work of art. Andrew Renton states: “If one does own the work, it is simultaneously ownerless.” What he means is that even though being collected does temporarily stabilize interpretation of a work, it also opens it up to new interpretations. And most crucially, “it’s difficult to put your fingers on where the work of art begins and ends.” The life of artwork can only be unforeseeable in the eyes of one of its audience.

Collecting becomes ever more unfathomable when dealing with one category of works, art as destruction. This is when artists are no longer satisfied by a fundamental concept like “art is creation”, thus turning around to commit to the idea of destruction as a creative process. Many artists have done this for different purposes and with different understandings and gestures. Whether they are implementing an iconoclastic act of vandalization or fighting against commercialization, whether they are resisting the norm or critiquing a social construct, these acts of destruction were provocative if not extremely.

What impact does the gesture of destroying have on artwork as a collectible? This question obviously defies generalizations but we can be pretty sure about one thing– all these works, at least all works below, have been collected by either institutions or private collectors. Even works that were not made to be collected, works that were meant to be temporary interventions or self-destructive, all figure out ways to seamlessly enter the logic of collection; for instance, through documentation like film and photography or through recreations. And the way these works were collected, archived, presented, and explained by various institutions and collectors shape the discourse around them and eventually become a part of them.

“There’s an inevitability to an artwork being collected,” Andrew Renton made this remark in the Collecting as Practice course when he mentioned the artist Gustav Metzger, the inventor of auto-destructive art. Despite the fact that Metzger resisted the commercialization of his works from day one by locating his works in the space of their destructions, you can still see an auto-destructive painting of his at Tate, a recreation of his first public demonstration of Auto-Destructive art on the South Bank in London in 1960. There seems to be some irony or at least ambiguity here in this recreation; like what Andrew Renton asked “what is it? an index to those works, a remembrance of those works, a symbol of those works, or is it those works?” The answer to this question might not be clear, but what is evident for Andrew Renton in this instance is that “There’s nothing that cannot be collected.”

In the aftermath of the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and during the cold war arms race, German artist and political activist Gustav Metzger invented auto-destructive art in 1959 as a strategy in his anti-nuclear and environmental activism. Auto-destructive art emphasizes the happening which aims to mirror what he thought was the deterioration of social and political systems around him.

His early trials were paintings with hydrochloric acid on nylon sheets that consequently disintegrated. The most iconic happening was in 1960 on the South Bank in London when in a militaristic gas mask and goggles he sprayed acid on red, black, and white sheets – the colors of anarchism.

_Man In Regent Street is auto-destructive._Rockets, nuclear weapons, are auto-destructive.

Auto-destructive art.

The drop drop dropping of HH bombs.

Not interested in ruins, (the picturesque)

Auto-destructive art re-enacts the obsession with destruction, the pummeling to which individuals and masses are subjected.

Auto-destructive art mirrors the compulsive perfectionism of arms manufacture – polishing to destruction point.

Auto-destructive art is the transformation of technology into public art. The immense productive capacity, the chaos of capitalism and of Soviet communism, the co-existence of surplus and starvation; the increasing stock-piling of nuclear weapons – more than enough to destroy technological societies; the disintegrative effect of machinery and of life in vast built-up a reason the person,…

Auto-destructive art is art which contains within itself an agent which automatically leads to its destruction within a period of time not to exceed twenty years. Other forms of auto-destructive art involve manual manipulation. There are forms of auto-destructive art where the artist has a tight control over the nature and timing of the disintegrative process, and there are other forms where the artist’s control is slight.

Materials and techniques used in creating auto-destructive art include: Acid, Adhesives, Ballistics, Canvas, Clay, Combustion, Compression, Concrete, Corrosion, Cybernetics, Drop, Elasticity, Electricity, Electrolysis, Feed-Back, Glass, Heat, Human Energy, Ice, Jet, Light, Load, Mass-production, Metal, Motion Picture, Natural Forces, Nuclear Energy, Paint, Paper, Photography, Plaster, Plastics, Pressure, Radiation, Sand, Solar Energy, Sound, Steam, Stress, Terra-cotta, Vibration, Water, Welding, Wire, Wood.

As a part of the first Destruction In Art Symposium (DIAS) held in London in 1966, organized by Gustav Metzger and John Sharkey, artists like Yoko Ono, Wolf Vostell, and Al Hansen came together with the aim to “to focus attention on the element of destruction in Happenings and other art forms, and to relate this destruction in society.” American artist Raphael Montañez Ortiz smashed a grand piano with a hammer in a provocative performance. This piano belonged to Fran Landesman and had been used to compose a number of her popular musicals, and this happening took place at the London home of Landesman following Landesman’s invitation. This performance is possibly an attempt to expand what is considered music and how an instrument can be played, or possibly a ritual of violence. Throughout his career, Raphael Montañez Ortiz has done over 80 piano deconstruction performances in museums and galleries around the world.

He commented on destructivist artists, “Theirs is an art which separates the makers from the unmakers, the assemblers from the disassemblers, the constructors from the destructors. These artists are destructivists and do not pretend to play at God’s happy game of creation; on the contrary, theirs is a response to the pervading will to kill.”

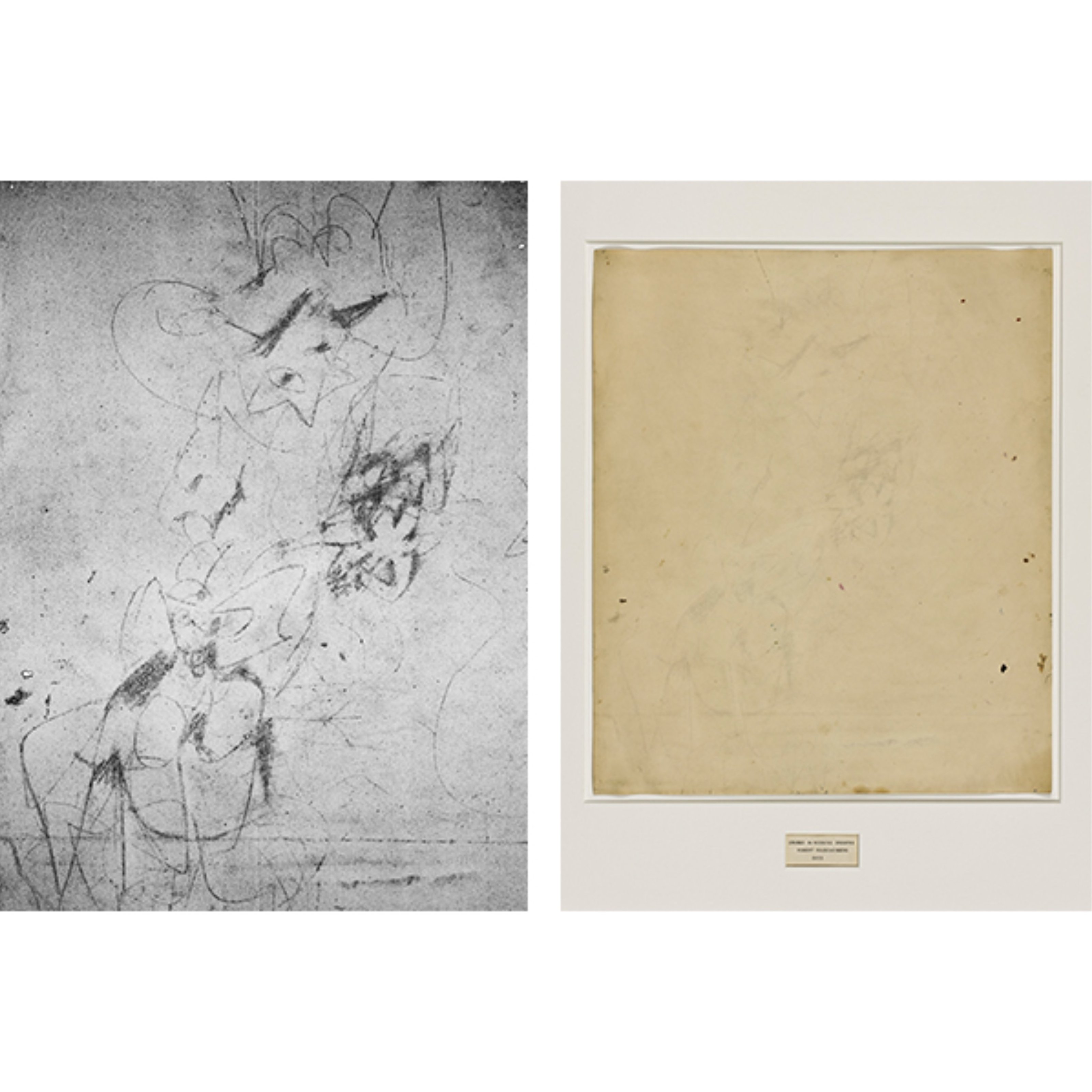

An iconic figure in the pop art movement, Robert Rauschenberg is well-known for his Combine paintings in which he incorporated everyday objects and blurred the distinction between painting and sculpture. In his early career, he befriended Josef Albers, a founder of Bauhaus, as well as John Cage, an essential avant-garde music composer and theorist. Under their influence, Robert Rauschenberg never stopped questioning the existing boundaries of art and continuously sought out innovative approaches in his practice for more than 50 years. Though destruction was not a central theme in his experiments, there was one instance in his early practice when 27-year-old Robert Rauschenberg asked Willem de Kooning whether he could erase one of his works. Upon de Kooning’s agreement, Rauschenberg ‘erased’ de Kooning’s graphic sketch over two months and retitled it “Erased de Kooning Drawing” (1953).

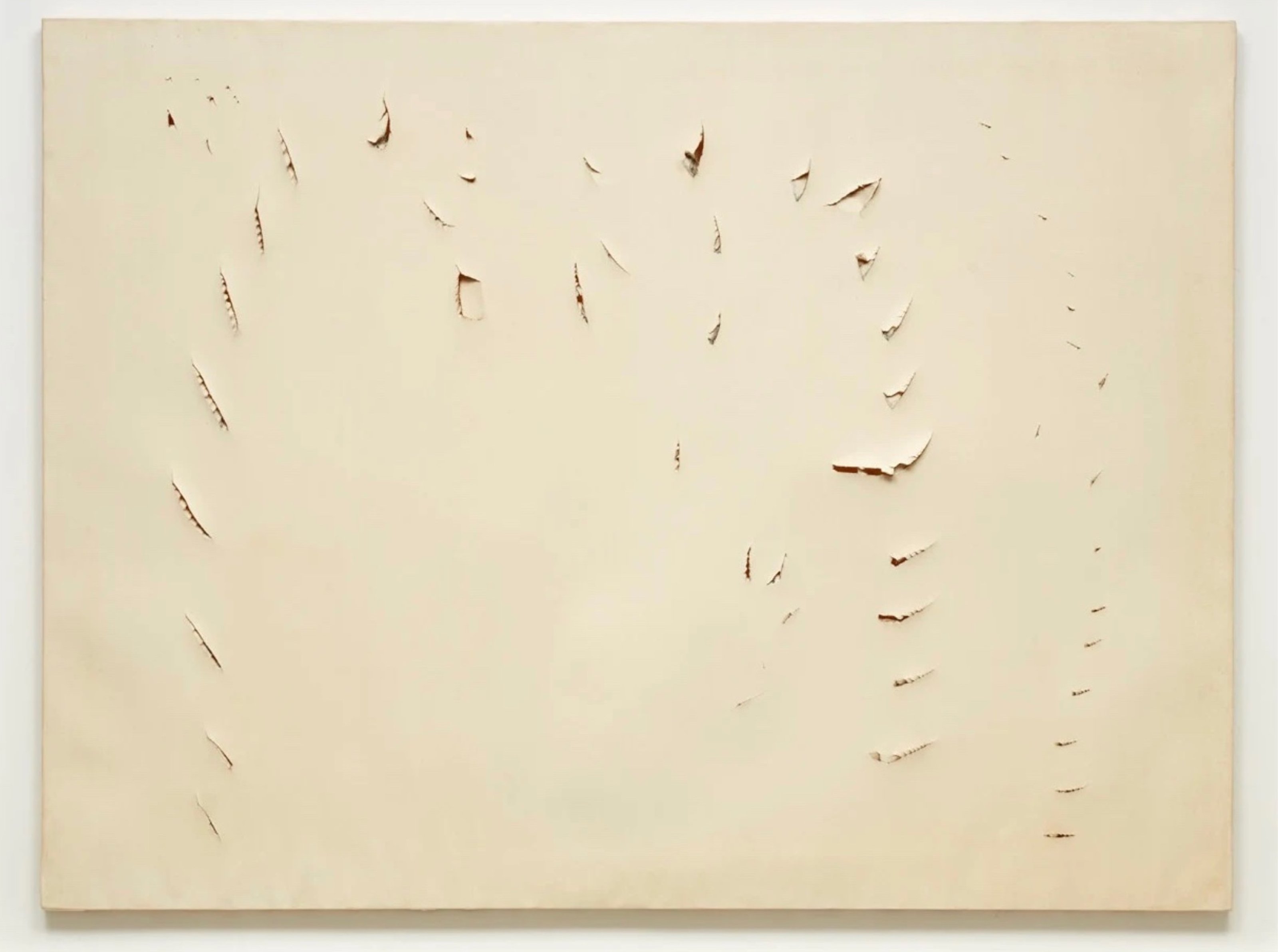

Lucio Fontana is an Argentine-Italian painter, sculptor, and founder of Spatialism. He turned away from the virtual space of traditional painting and tried to unite art into the real space. Beginning in 1945-50, Lucio Fontana punctured the surface of his canvases in his Buchi (holes) cycle. From 1958, he started to slice the matte, monochrome surfaces of his canvas, thus transforming the two-dimensionality of canvas into an exploration of the space behind it. He was one of the earliest European artists who was committed to the idea of art as gesture, painting as performance. We can definitely see the continuation of such a concept in Mezger’s auto-destructive paintings and Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing.

In the summer of 1970, John Baldessari incinerated all his paintings from 1953 to 1966 at a local crematorium and conceived it as an artwork in itself called Cremation Project. John Baldessari is an American conceptual artist known for his use of found photography and appropriated images. Initially a painter in the 1960s, he began to work in multiple media in 1970, including printmaking, film, video, installation, sculpture, and photography. In this sense, the cremation of his paintings in 1970 seems to be a turning point for his practice, marking an attempt to break away from the past and to start something new. This seems to be a rather personal gesture.

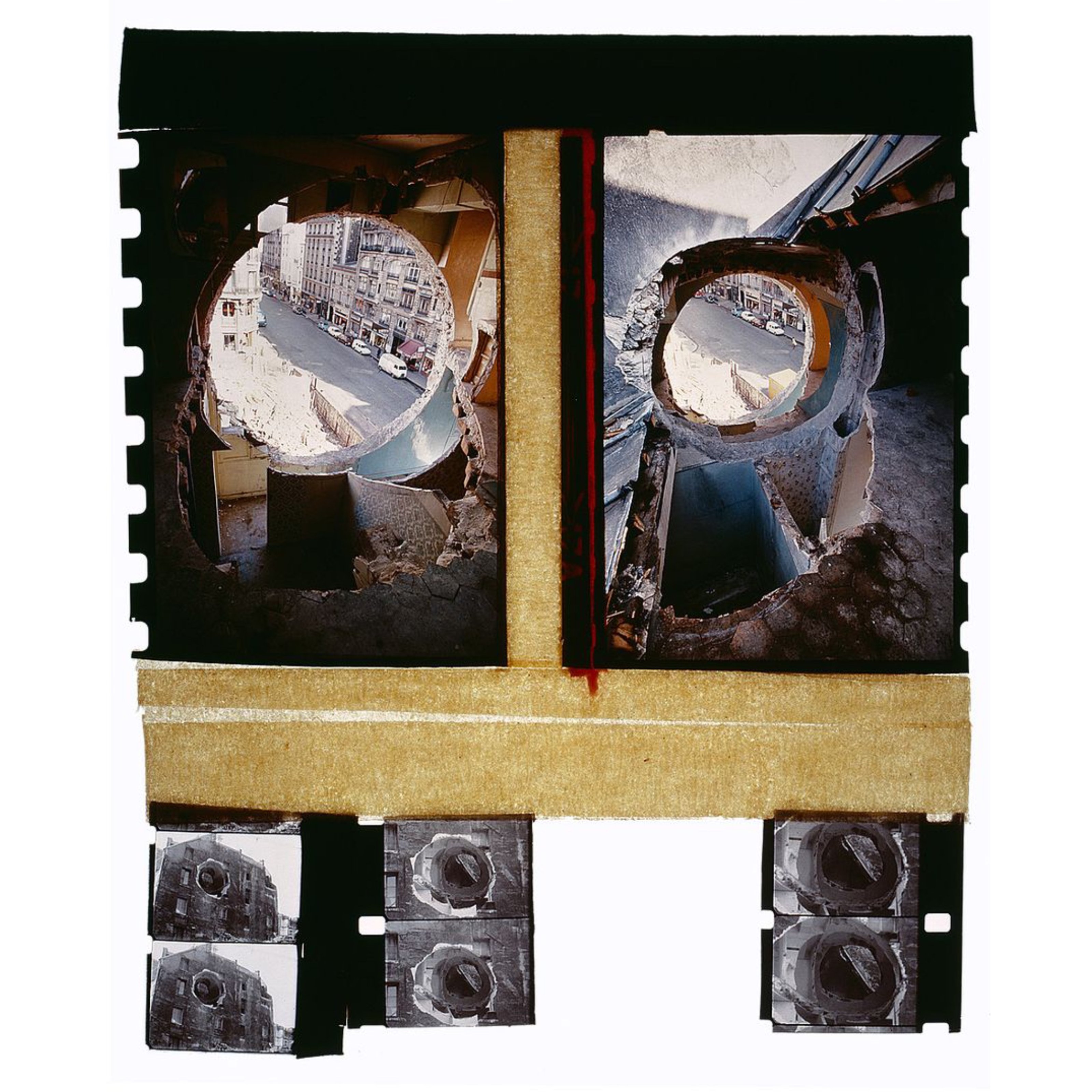

Gordon Matta-Clark is an American artist best known for his site-specific interventions during the 1970s. He studied architecture at Cornell University, but instead of building architectures, his works engage with the idea of removal and deconstruction carried out on architectures that are soon due for demolition. In 1975, invited by city officials in Paris for the ninth Paris Biennial, Matta-Clark was offered a pair of early seventeenth-century houses adjacent to the Centre Pompidou building site that was slated for demolition. Matta-Clark then implemented a conical cut on the building, mimicking a monstrously sized drill drilling through. The project involved multiple media, including roasting 750 pounds of beef for passersby on the Pompidou plaza, the actual deconstruction project, a film of the undertaking, as well as photomontages. The buildings were destroyed soon after the completion of the piece.

In 1974, Matta-Clark and helpers split an old frame house in New Jersey, owned by New York art dealer Holly Solomon in two parts. A film of the undertaking was produced, and the house no longer stands today. Matta-Clark didn’t care whether this work would be buried or destroyed but tried to transform how people looked at art and its temporality. He called these types of building non.u.mental — something destined to destruction.

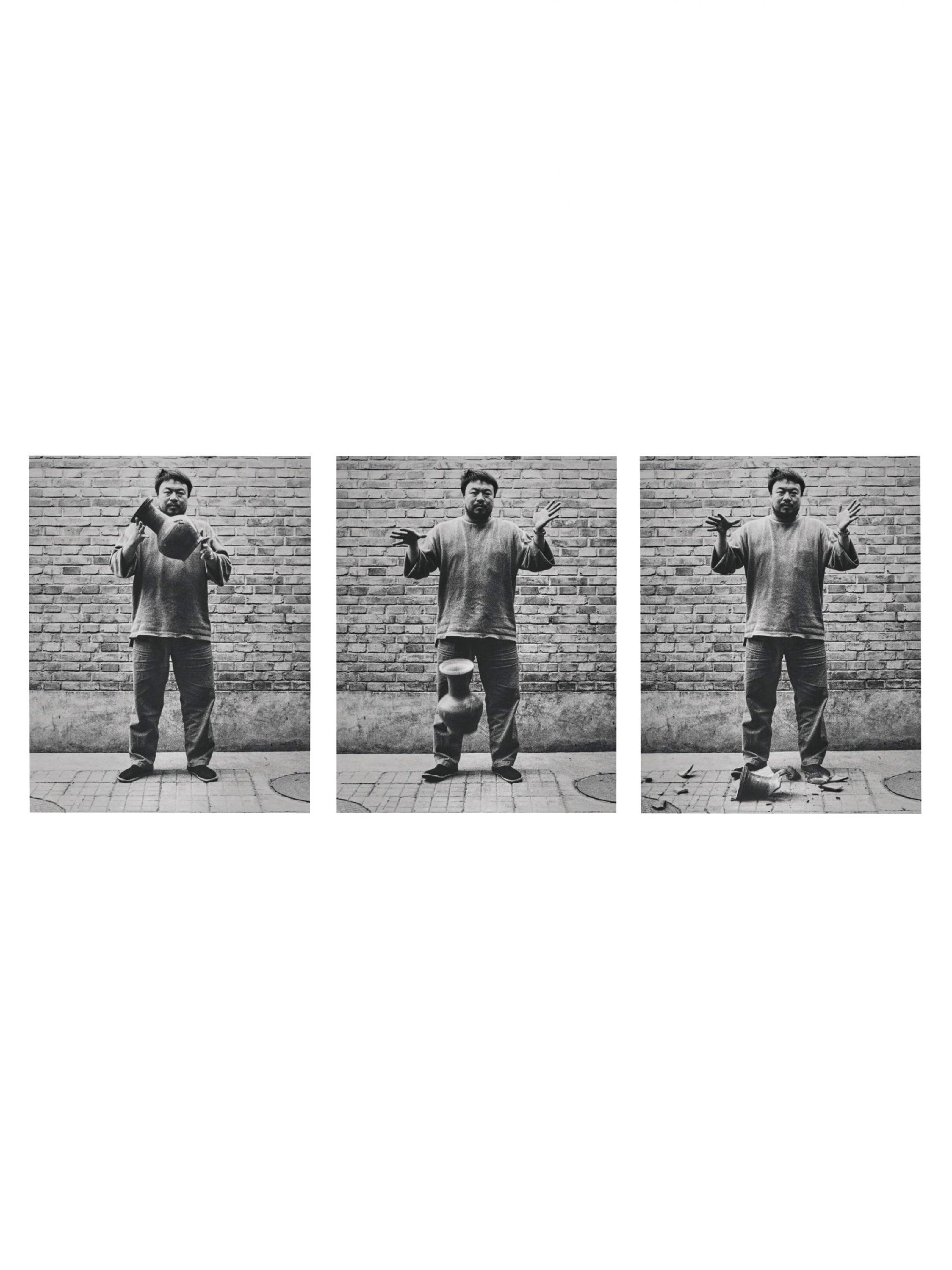

Ai Weiwei, a Chinese contemporary artist, made Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn as one of his early works. In this iconoclastic gesture, Ai dropped a Han dynasty urn to the floor. He considered this urn a “cultural readymade” since not only does it have monetary value but also cultural and nationalistic value. The Han dynasty plays a crucial role in the identity of Chinese people, thus, smashing a Han dynasty urn is like denying a part of Chinese heritage and identity. Through this act, Ai questions how and by whom cultural values are created. The gesture of destroying is only one among many provocative gestures in Ai’s work.

The act of demolishment can also be used to highlight its opposite, the presence of objects. After compiling an inventory of his belongings that ran to 7,227 items over three years, British artist Micheal Landy publicly dismantled and demolished everything that he owned as a 37-year-old man in an empty shop in Oxford Street in central London. To destroy every single item he owns, including his car and his artist archive, the process took Landy and his team of 12 assistants two weeks. This process of destruction ruthlessly reminds people of consumerism and ownership, and most importantly their normalization and excessiveness.

In 2018, one of street artist Banksy’s most iconic works “Girl With Balloon” was sold at Sotheby’s in London for $1.4 million. As the auctioneer slammed his gavel, the painting started beeping and the bottom half of the painting was shredded by a secret shredder Banksy had built into the bottom of the picture frame. The work was retitled “Love Is in the Bin.” Three years after the initial auction, “Love Is in the Bin” sold for $25.4 million.

The tale of this painting is now sensational and even overused. Its precise self-consciousness as a collectible on the market and its aim to disturb the logic of selling and collecting actually made it more valuable according to the market. Isn’t this another telling evidence for “There’s an inevitability to an artwork being collected. There’s nothing that cannot be collected.”

Not only is there an inevitability to an artwork being collected, but a work of art also anticipates its life as a collectible. Then, how does this consciousness inform art-making and art-collecting? We invite you to attend Andrew Renton’s lesson on collecting as a practice. In this course, you can learn about how collecting has shaped artworks and artists and how being collected is central to the life of an artwork. For those who make art, Andrew Renton’s anecdotes on Andy Warhol and Picasso might give you a whole new perspective on the commercialization of your works. For those who collect art, Andrew Renton teaches about the important roles collectors play in the life of artworks and the respective responsibilities you should be aware of.

Enroll now in Collecting as Practice – What Makes a Work of Art Work? taught by Andrew Renton available on Collecteurs Academy Library Access. Watch anytime on your own schedule.